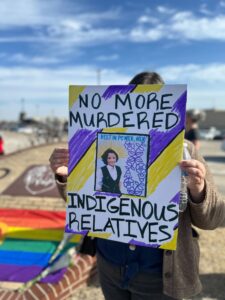

The Tulsa LGBTQ community is in dire need of healing since the back-to-back anti-LGBTQ threats, including mounting anti-LGBTQ legislation and mourning the deaths of notable LGBTQ activists, youth, and parents. Within the last couple years the community lost Fernande “Fern” Galindo, nonbinary parent, LGBTQ activist, and transformative justice organizer, Nex Benedict, the young possibly two-spirit, nonbinary, transgender youth, and Nancy McDonald, the trailblazing founder of Tulsa’s PFLAG chapter. The deaths of Galindo, Benedict, and McDonald will never be forgotten.

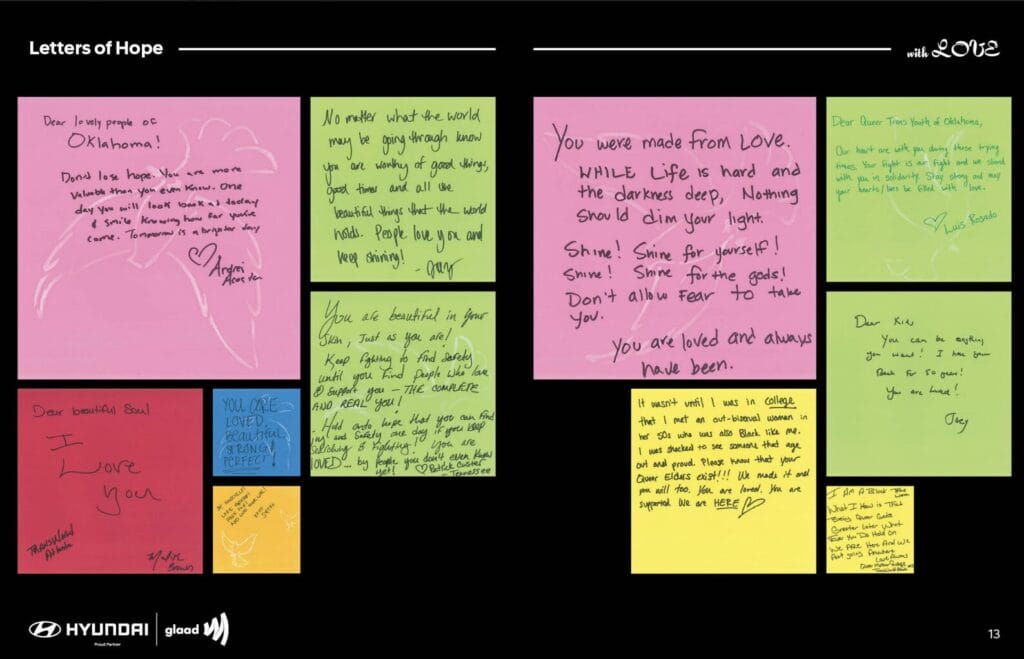

In fact, the LGBTQ community far and wide has rallied for Tulsa’s 2SLGBTQ community. Youth Services of Tulsa, the Prism Project, Hyundai, Innocean, and GLAAD worked in collaboration to honor those LGBTQ community members who continue to organize and fight for Tulsa in the face of growing adversity. On September 7 the Youth Services of Tulsa (YST) announced the newest addition to their art collection, a mural designed by the “LA Hope Dealer” Corie Mattie, which was funded by Hyundai car dealers, a GLAAD Media Awards sponsor and GLAAD partner. The piece will be housed in Youth Services of Tulsa Youth Coffee House.

Through collective grief, community has come together.

“Creating this piece for LGBTQ youth in the South was incredibly meaningful to me. The phrase ‘They tried to bury us, they didn’t know we were seeds’ captures the essence of resilience and growth, especially for those who face suppression,” Mattie said to GLAAD in an email statement. “In regions where acceptance is harder to come by, I wanted to create something that would remind these youth that, despite the adversity they face, they have the power to rise, grow, and flourish.”

View this post on Instagram

The organizers of the mural were Josiah Robinson, lawyer and managing director of the Prism Project, and Amy McGehee, board president of PFLAG Tulsa, doctoral candidate at Oklahoma State University and parent. They worked with Hyundai, Mattie, Youth Services of Tulsa, and GLAAD to coordinate the mural’s drop off with a series of letters LGBTQ celebrities, activists, and guests of the New York GLAAD Media Awards took part in.

Read the GLAAD letter book here.

“[The letters and mural] are so symbolic of, I think, of the resiliency, and the community at-large catching a breath,” Robinson said.

Robinson shares that the demanding need to organize and push back against Oklahoma’s inextricable anti-LGBTQ climate has been exhausting. The ACLU tracked 55 anti-LGBTQ bills introduced into Oklahoma’s state legislature this year. Most have failed, but the violent public perception these bills influence have lingered over the state.

Though still high – general support for the LGBTQ community has declined since last year, according to 2024 Accelerating Acceptance data.

McGehee, reflecting on her inner child, said that to receive messages like this as an LGBTQ youth would’ve meant everything to her and her adult peers. As adults who worked on culmination of these positive messages for LGBTQ youth, Robinson and McGehee, think that the need for youth to see positive LGBTQ representation is salient.

The parent has built her own path, but it is deeply informed by LGBTQ elders of the past. McGehee remembers within recent years meeting Nancy McDonald one last time before she died – Robinson introduced them. McDonald was known for her bravery in telling her story as a lesbian in 1987 and starting Tulsa’s PFLAG chapter. When McDonald met McGehee, she was looking to pass the baton.

“Nancy and I instantly connected. I think that it was just amazing to see someone who has done so much of the work that has really provided me a foundation to do the work that I’m doing now,” the Tulsa PFLAG board president shared. “It wouldn’t be possible.”

While it feels difficult to get outsiders to understand and accept the humanity of LGBTQ people in Oklahoma and beyond, “hope” is a central theme in the mural’s making. Robinson worked to make sure that all parties involved were connected, ensuring a successful send off for organizing partners to youth.

One of those organizing partners was Katie Powell. She has been in her role as an LGBTQ program coordinator for almost three years, while having worked at Youth Services of Tulsa for six years. Powell has long worked with the Prism Project, Oklahomans for Equality, Robinson and McGehee, as she has with McDonald, Benedict, and Galindo.

“It’s been so amazing,” said Powell. “Through that work, I think we have kind of gotten louder in our echoes, and so, I think that is how we’ve been identified to (kind of) be a part of this project,” Powell said.

The day of the mural and letter-book drop-off at Youth Services of Tulsa, Powell recalls Mattie “tagging” kids’ white T-shirts with designs if they asked. Mattie stayed and met with youth as the nonbinary flag filled with signatures from the school walkouts and vigils honoring Nex Benedict waved amongst them.

Robinson, now 30-years-old, says he was a client of the Youth Services of Tulsa when he was a teenager. Robinson, not openly queer at the time, remembered seeing affirming messaging for LGBTQ youth just like him.

“That was something that was very rare in my life,” he recalled. “It feels kind of like a full circle moment, in many ways, to be a part of this mural living at YST, and just offering a message of hope to LGBTQ+ youth.”

Similarly, McGehee shares that Oklahoma is a challenging place to be a queer person, especially for queer and trans youth.

“Whenever we had this opportunity to bring in a message of hope – especially in the wake of Nex Benedict’s death, which happened not too long ago – it just felt like it could be a really powerful way to move toward that healing that we all wanted,” McGehee adds.

GLAAD’s most recent data found that media exposure is also associated with higher levels of comfortability with our community.

As she painted the mural, Mattie indubitably thought about Benedict.

“Nex deserved to be in an environment that nurtured and provided safety – where no one, especially a young person, should ever feel the need to defend their true self. If the world were more accepting, kids like Nex would still be here today,” Mattie said.

The intention for Mattie is to understand the circumstances of the policy war on LGBTQ youth by remembering what it was like to be one. Meanwhile, LGBTQ adults, with children of their own, have to protect themselves and their family.

Like Robinson, McGehee grew up in Oklahoma, and so have many of the LGBTQ adults fighting and organizing in Tulsa today. The LGBTQ population in Oklahoma is 3.8%, ranking 34th in LGBTQ population size compared to other states, and of that percentage, 38% of LGBTQ people have children, according to the William’s Institute.

“I keep my little Fern jar,” Powell said. Galindo also left this earth a parent. Powell recalls mourning with loved ones and family at the memoriam. They handed out jars and slivers of orange paper to one another. “And it was just like: you write your message to Fern, and what they meant to you,” Powell said, “you roll it up and put it in that little jar. And then, I just kept mine on my desk, just to remember…” Beginning to choke up. Powell remembered how fiery and passionate their friend could be, the vigor they stored in their intention to heal communities. Much of their work focused on feeding Tulsa, and building stable housing while understanding their target audience as a spectrum of people with overlapping identities that society overwhelms circumstantial privileges and oppressions.

“I worked with Fern quite a bit through community activism,” Powell reflected. “Fern always showed up everywhere, if there was good trouble to be made, Fern was there.”

Robinson, as McGehee and Mattie spoke of Nex, McDonald and Galindo. Robinson said “I think of Fern a lot.” Galindo passed by suicide just last year, just months before Benedict’s death, which was ruled a suicide.

Galindo, 38, was the founder of the Tulsa Intersectional Care Network (TICN), an organization that provided mutual aid, including meal trains to disabled, BIPOC, queer, and other Tulsans in need while facilitating community-building.

The mural is expected to make trips to a number of places in Tulsa including Oklahomans for Equality at the Dennis R. Neil Equality Center, University of Tulsa, Tulsa Pride, Little Blue House, and many more.

“I’m so excited for this mural to be a mobile beacon of hope,” Powell said.