“What do we do?” has been a question that has echoed in the hallways of my mind since I left Tulsa, Oklahoma last March. At that time – not so much different than now – Oklahoma was battling horrendous anti-lesbian, gay and bisexuality laws as well as anti-transgender, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming laws disproportionately targeting youth. Tulsa, it seems, is a beacon of hope for the rest of the state as activists push back against anti-LGBTQ sports bans, health care bans, and education bans.

Essentially, living in Oklahoma as an LGBTQ person means you’re a second class citizen by law. However, Dorothy Ballard, Crista Patrick, and Olivia Cotter are activists committed to fighting for LGBTQ equality in Tulsa regardless of the odds.

Even so, these activists now mourn one of their community members who died by suicide.

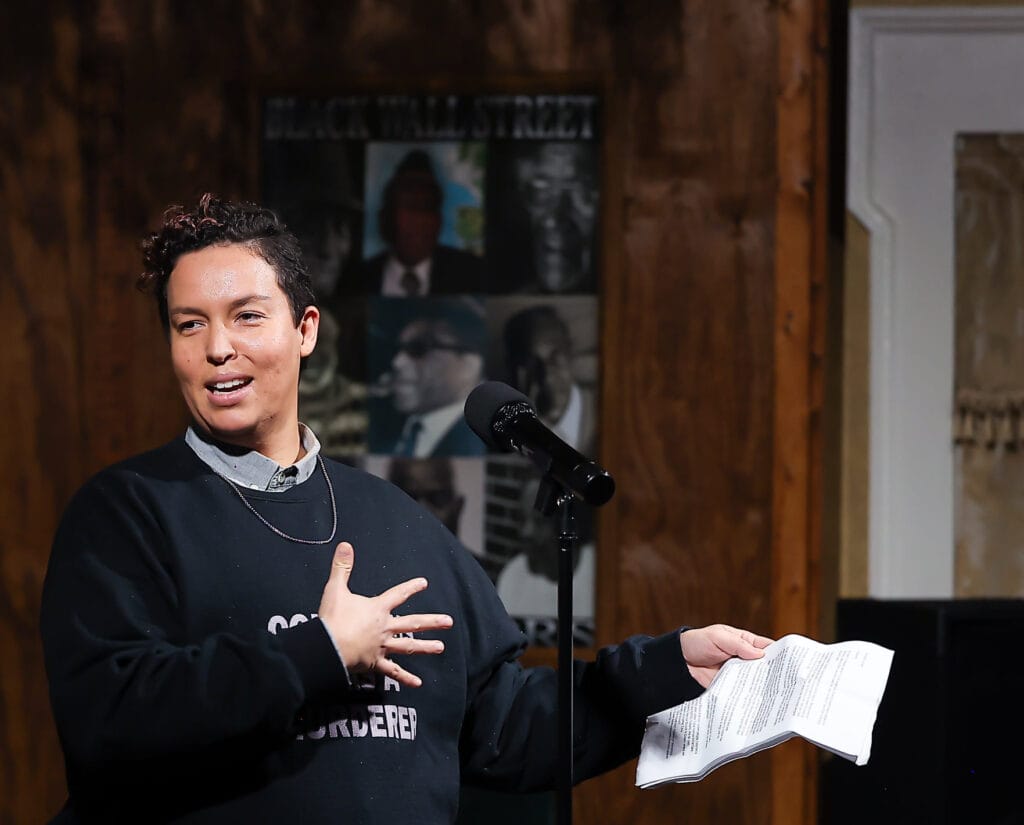

His name is Fernande “Fern” Galindo, 38, the founder of the Tulsa Intersectional Care Network (TICN), an organization that provided mutual aid, including meal trains to disabled, BIPOC, queer, and other Tulsans in need while facilitating community-building.

Galindo, a parent, an activist, and a friend asked me the question “What do we do?” with deep desire, and passion, to change cities like Tulsa and St. Louis (where they organized with Metro Trans Umbrella Group). Yet, they already knew the answer to their question. Looking back, I know that this was a question that burdened their soul, their being, their experience under the discriminatory conditions Oklahomans and Missourians face.

When Galindo talked to me about change, or “what we should do” this is what he said:

“I mean, short-term goals are feeding our people, making sure that housing stability is a thing, and we do that in the ways that we can,” Galindo told me in our first and only interview together. “Through the Intersectional Care Network we’re not necessarily only focusing on one particular marginalized identity, but more how when you have marginalized identities on multiple planes, the intersection of those means you have a greater need.”

Galindo went on to speak on intersectional struggles that can show up for just one person. With that in mind, they found ways to build community partnerships that integrated a community of people, their needs, and mutual aid for a better quality of life; to eradicate common struggles people face.

Cotter says that Galindo was this way because they “embodied the soul of community.”

“Fern was a force of nature,” said Cotter. “Everywhere they tread, they wove connections, built bridges, and orchestrated gatherings that resonated with the pulse of unity. Their innate ability to draw people together was nothing short of magical. They could transform strangers into friends in moments, effortlessly creating a sense of home wherever they ventured.”

The close friend is an advocate working with Oklahomans for Equality (OKEQ). Cotter, with interim Executive Director of OKEq Dorothy Ballard, Galindo, and others are responsible for helping to pass a Resolution “designating the City of Tulsa a safe, inclusive, and welcoming community and reaffirming the City of Tulsa’s commitment to fostering a safe, inclusive, and welcoming City.”

Ballard had great respect for Galindo.

“Fern embodied love in action, fiercely providing to our communities the joys, resources, and advocacy they were so often denied systemically,” Ballard told GLAAD in a statement. “Their gift was inspiring a depth of empathy that moved others to radical kindness and activism. They live on in the work that continues for all marginalized people in Tulsa and beyond.”

The activist leaves behind a legacy.

“Words falter in capturing the breadth of Fern’s presence,” Cotter said.

Galindo involved themself with the Abolition Study Group. The group aimed to facilitate conversations about the impact of the prison industrial complex and prison abolition, particularly on Black and Brown populations. They also worked tirelessly to support Tulsa’s LGBTQ community by organizing a nonbinary parents’ day, elderly adults’ art day, and a volunteer barbecue. They were involved with the Bible Belt Queers and Black Queer Tulsa, in addition to speaking on panels presented by Freedom Oklahoma about mutual aid and community resources, and presented information on food insecurity at a statewide conference on food banks.

As a result of their tireless efforts to create change, Freedom Oklahoma created the Fern Galindo Community Builder Award in honor of Galindo’s community advocacy.

View this post on Instagram

Just before Galindo’s passing, the city of Tulsa failed to pass an anti-discrimination ordinance with consistent coverage for gender identity, and sexuality amidst veterans, age, and housing. The ordinance didn’t pass with a 4-4 vote with one abstention recorded as a “no” vote.

The Council Chair Crista Patrick – who introduced the revisions for a vote – said Galindo was an inspiration.

“Fern was a friend, a fierce advocate, and a loving parent,” said Patrick. “I will miss them so very much. It is a tragedy that they are not with us anymore. People like Fern and myself and my daughter, and half my friends, are the reasons I wanted to align the anti-discrimination policies in the first place. I am just forever sorry that [the policy] not passing may have added to their despair.”

Galindo’s son, Mariano Alejandro (Alex), daughter, Eva Carina, and son, Nicolas (Nico) Angel survives them; her mother, Irene Dornberger; sisters, Rebekah Dornberger and Patricia Maxwell; and brothers, Paul Buendia and David Dornberger.

“In honoring Fern’s legacy, let us carry forward their spirit of inclusivity and unwavering commitment to fostering togetherness,” Cotter said.

GLAAD Media Institute provides activist, spokesperson, and media engagement education, consultation and research for LGBTQ and allied community members, the media industry and advocacy organizations desiring to deepen their media impact