By Dionne N. Walker

Images—often heartbreaking ones of pain, illness, and slow death—were among the first ways the American public became aware of the HIV epidemic. Long after those disturbing 1980s pictures first made suffering the face of HIV, a Southern art exhibit on display at Buckhead Art & Company is using joyous portraits of people living with HIV and allies to break down longstanding stigma.

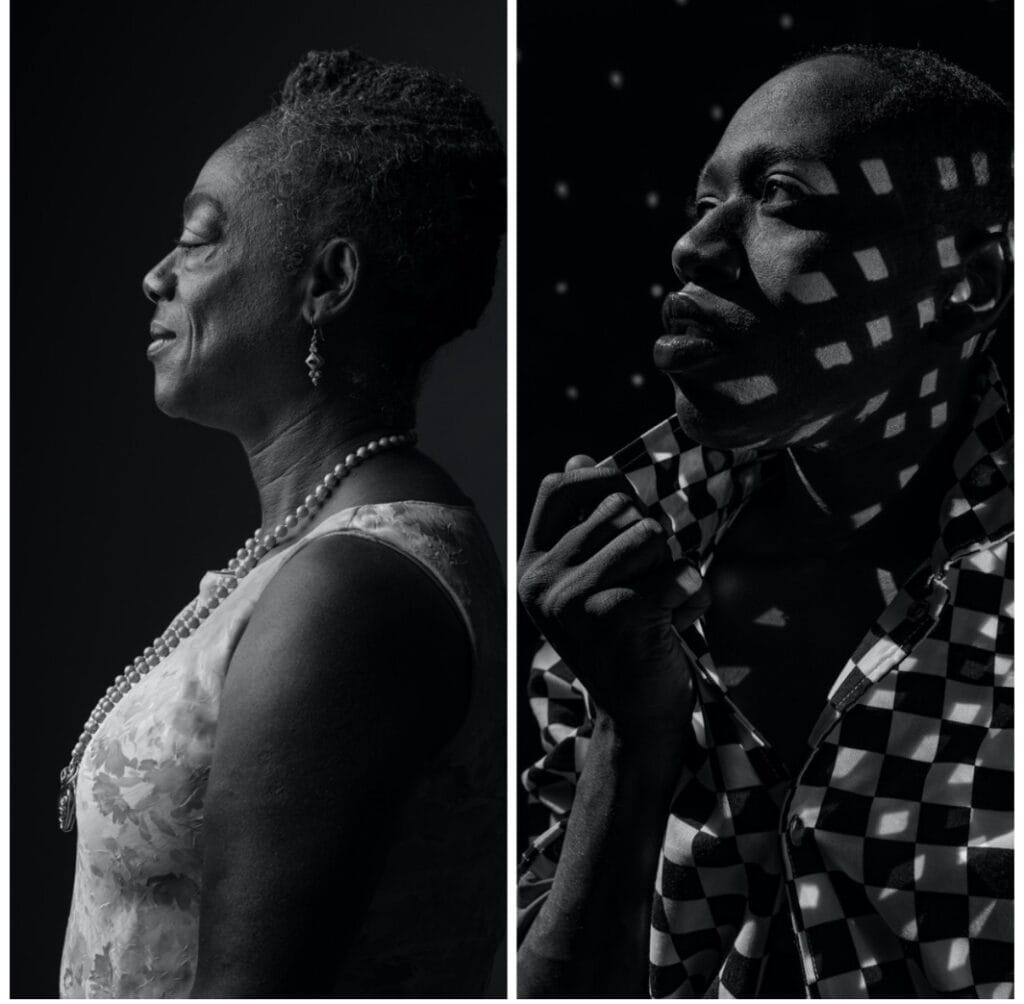

“Stories of Triumph” features images of 30 Southerners making waves in the HIV space. The showcase debuted on World AIDS Day in Atlanta, a city among the nation’s hotbeds for new HIV acquisitions. Images ranging from a sensitive snapshot of a couple’s embrace to a nuanced close-up reminiscent of old lounge singers make up the exhibit. Freelance photographer Sean Black captured the images during a three-month road trip from the Mississippi Delta to the Carolinas and all points in between.

“We’re really kind of sounding the horn in a creative storytelling way … using art as a tool for social justice and advocacy,” says Candace Meadows, who oversaw the funding of the project as a director of partnerships and initiatives at Emory Compass Coordinating Center at Rollins School of Public Health. “Art, fashion, film, theater draw people in with visual imagery that oftentimes tell bold stories that move us in ways that written words don’t.”

Atlanta’s Emory University, a leader in HIV research, partnered with Gilead Sciences to fund this and similar projects through their 10-year COMPASS Initiative. COMPASS, short for Commitment to Partnership in Addressing HIV in Southern States, is a $100+ million grant/training program targeting community-based organizations working to combat the HIV epidemic in the Southern United States.

On November 30, the Biden Administration released “A Proclamation on World AIDS Day, 2023, pledging to ask Congress for additional funding for the Department of Health and Human Services’ Ending The HIV Epidemic Initiative.

“I have asked the Congress for $850 million for the Department of Health and Human Services’ Ending the HIV Epidemic Initiative to aggressively reduce new HIV cases, fight the stigma that stops many people from getting care, and increase access to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) — a critical drug that can help prevent the spread of HIV,” Biden said.

Although the U.S. South accounts for only 38 percent of the country’s population, the region accounts for 52 percent of new HIV diagnoses, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Five years in, the program has distributed millions collectively to 393 partners like Sean Black—a native Floridian living with HIV. Black is also the son of a military photographer who knew the power images can have to change perception. The initiative awarded Black a $25,000 grant to go on a road trip gathering the most poignant images of COMPASS program partners to share with those who rarely encounter anyone connected to the virus.

The photos veer far off from the traditional images long associated with HIV; there are no gaunt faces, nobody in a bed or sick appearing. Instead, Black shows subjects relaxing, laughing, loving, and more. Many look boldly into the camera, while others seem caught in intimate moments of personal emotion.

Black says he immersed himself in the subjects’ activities – from handing out condoms to enjoying a catfish dinner – to capture the subtle beauty in their day-to-day efforts. Showing that normalcy, Black says, is critical to building bridges.

“Those people will then reflect similar people [for audiences], that archetypal representation in their own lives,” he says. “Hopefully, people will be uplifted.”

HIV is mission work

In one frame, a cherubic, curly-haired Black woman smiles broadly, her hand gently tapping her chin, her face upturned as if receiving a message from the heavens. The subject, Atlanta-based National Public Health consultant Leisha McKinley-Beach, beams a sort of quiet satisfaction – the result of spending more than 30 years helping people living with HIV. That journey began when a then 17-year-old McKinley-Beach stumbled on an HIV peer educator group in college. Already gearing toward health services, the teen decided to join; it would later lead to her holding the hand of a young man as he died from AIDS.

The experience was transformative.

Leisha McKinley-Beach poses for “Stories of Triumph” photo exhibition. (Image: Sean Black)

“I heard the voice of God saying to me, you have one mission in life, and that is to love,” she says. “I have been committed to that mission every day. That is my story of why HIV is so important to me – it is mission work.”

McKinley-Beach says she believes images of everyday folks in the HIV space can go a long way to building bridges and humanizing people who are living and thriving with HIV.

“One of the things that we are still working on is what the blueprint looks like in ending stigma with HIV,” she says. “There’s more to HIV beyond just data and statistics, and when you see the images that are displayed in this gallery piece, you see aunties and mamas and brothers and sisters. It puts a face on it.”

Decades after HIV/AIDS first entered the public consciousness, the work of undoing people’s HIV/AIDS assumptions remains as relevant as ever. In June, the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS passed a resolution calling on healthcare providers and everyday people alike to combat HIV stigma actively. The resolution came ahead of Zero HIV Stigma Day in July.

HIV stigma often pairs with subtle prejudice to limit resources coming into HIV-affected communities, agreed a panel of experts who gathered at Atlanta’s Buckhead Art & Company for a panel discussion following the photo exhibit’s unveiling.

“Racism is most of it,” panelist Dr. Sophia Hussen told the audience at the Dec. 1 event. “That’s not limited to our community, but it’s a specific barrier to everything we’re doing.”

The panel, dubbed “Cocktails and Conversations,” featured a diverse list of experts discussing structural barriers and other blockades to lower HIV infection numbers in Southern communities.

Included was Dyllón Burnside, an actor and LGBTQ+ advocate known for playing dancer Ricky Evangelista on the FX television series “Pose.” Despite the show’s popularity, Burnside felt there was still an absence of particular voices from the HIV communal discussion.

“Certain identities are left out of the conversation,” he said, adding that failing to represent particular communities has a direct relationship with HIV knowledge and prevention. “When we negate Black trans men or women, we see increases in those communities.”

Panelist Larry Scott-Walker, Executive Director of Atlanta Black gay men’s support group THRIVE SS, agreed that there remains room for voices to be added to the HIV conversation. Scott-Walker said exhibits like “Stories of Triumph” helped reduce stigma by showing there’s much more to living with HIV than the negative.

“People living with HIV deserve to experience pleasure,” he said. “It doesn’t have to be, oh my god, I have HIV,” Scott-Walker added.

In the audience, Black looked on proudly as attendees crowded the gallery and marveled over photos, turning the image of HIV on its head.

“I want to see the good that’s being done. We see so much negativity,” Black says. “When you focus on people, I think there’s a lot of beauty as well.”