“We’re all just one influential TV character away from changing the world.”

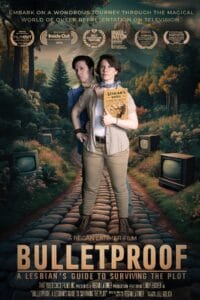

That bold assertion echoes through the final moments of Regan Latimer‘s debut feature documentary, Bulletproof: A Lesbian’s Guide to Surviving the Plot — and it sticks.

From the moment the film opens with an animated character named Sally, curled up watching a tender queer love story on TV, we’re drawn into a candid, clever, and cuttingly insightful journey through the media minefield that has been lesbian representation on television. A disembodied narrator warns Sally — and us — about the recurring fate of lesbian characters who, too often, don’t survive their own plots. A bullet here. A tragic death there. And always, a love story left unfinished.

In Bulletproof, filmmaker Regan Latimer takes us by the hand as our “friendly neighborhood lesbian guide” and asks the burning question: Why do lesbian characters keep dying on television? Her exploration unpacks decades of queer tropes with a refreshing blend of humor, academic rigor, and personal vulnerability.

Blending sharp critique with nostalgia and pop culture glee, Latimer chronicles her own journey as a queer kid in the ’80s, clinging to TV characters like Ace from Doctor Who, Jo Polniaczek from Facts of Life, and even the camp of Wonder Woman. Representation was rare, but she found meaning in the margins — gravitating to anyone who made her feel “less weird, less alone.”

The narrative is framed around Lindy, a fictionalized surrogate for Latimer, who introduces us to the rules of survival for lesbian characters on TV, and the emotional rollercoaster that comes with falling in love with a character whose storyline you already suspect won’t end well. The film becomes a patchwork of interviews with writers, showrunners, media experts, fans, and activists who all weigh in on the cultural and psychological stakes of representation. We hear from real people whose identities were shaped by fictional ones.

Megan Townsend, GLAAD’s own Senior Director of Entertainment Research and Analysis, puts it best: “Being from a tiny Midwestern town that didn’t have a single queer person afoot… seeing Callie Torres on Grey’s Anatomy as a fully realized person showed me that I can exist as I am.”

One of the most captivating revelations in Bulletproof is Latimer’s dive into the brain science behind representation. Through media psychology and the concept of “transportation theory,” the film explains how our brains can experience deep emotional attachment to fictional characters. As one psychologist in the film elaborates, the emotional processing of watching a beloved lesbian character die on-screen can mimic the feeling of real-life loss. Our brains code these fictional relationships as meaningful because of the immersion, the investment, and the representation they offer.

In one especially poignant moment, Latimer reflects on the character Denise from The Walking Dead, whose sudden and brutal death via arrow to the eye in 2016 became her breaking point. That spring, a wave of lesbian characters were written off with devastating finality. It was a pattern that prompted not just anger, but action. Bulletproof was born out of that rupture.

While the documentary is filled with painful memories and systemic criticism, it’s far from dour. Latimer infuses the film with levity and love, proving that storytelling is both a salve and a strategy for change. From Buffy the Vampire Slayer to The L Word and beyond, she traces a lineage of queer visibility and resilience that is both celebratory and cautionary.

Winner of the Grand Jury Prize for Best Documentary at Montreal’s image+nation, and Best Documentary at San Diego’s FilmOut, Bulletproof has become a breakout hit on the festival circuit. Its charm lies in its ability to bridge communities: it is as educational for the uninitiated as it is affirming for those who have lived through the emotional rollercoaster of queer fandom.

We sat down with the visionary behind the film to talk about queer media, survival, and what it means to tell the truth on and off screen.

Here is an exclusive interview with the filmmaker Regan Latimer!

GLAAD: When did the spark for the film first ignite for you? Was there a particular scene or show that tipped it over the edge?

Regan: It was kind of a period of time, but there was one specific moment that really got me. I was watching The Walking Dead with my partner, and the character Denise—who wasn’t even a major character, just the hopeful partner of one of the leads—was shot through the head with an arrow while she was finally saying she loved this other character. They made it as gruesome as possible. That was the moment I thought, “No more.” I felt someone needed to do something about this. And then I realized—I’m a filmmaker. So I got off the couch and decided I would be that someone.

GLAAD: That scene really stuck with me too. And I think your film really brings to light not just how short the timelines are for queer women on screen, but the grotesque violence often tied to their deaths.

Regan: Yes, and that was one of the most interesting parts of making the film—unpacking why it felt so visceral. I started Googling and discovered media psychology, which is how I found Aiden Hirshfield. Our first conversation lasted about three hours, and it was so validating. It helped me understand that I wasn’t a weirdo for feeling so deeply about it—there was a scientific reason behind those emotions. I knew I had to include that in the film because I’m sure many others have wondered the same thing.

GLAAD: You mentioned generational differences in how people have experienced representation. Can you speak more to that?

Regan: Definitely. I’m guessing you’re younger than me, and what I’ve found is that younger audiences didn’t necessarily grow up with the same lack of representation—or at least not in the same way. For older generations, just seeing a queer character, even if they were treated badly, was still something. People even older than me didn’t see anyone like them on screen at all. That really came into focus for me while making the film.

GLAAD: I definitely fall into that younger camp, and your film really illuminated the history I wasn’t fully aware of—like the whole “gay panic” era from the ’80s sitcoms. I’m thinking of Jo on Facts of Life.

Regan: Oh, yes—Jo! Before your time, but for us, it was like, ‘Why is she so cool?’ She was definitely queer-coded, even if the show never said it outright. But the show seemed to imply, ‘Don’t worry, she’s just a tomboy—puberty will fix it.’ It’s kind of mind-boggling looking back.

GLAAD: And yet, even with more representation now, we’re seeing signs that things might be slipping backwards again.

Regan: Unfortunately, I share that fear. Media has always been a kind of thermometer for what’s happening in society. Right now, it does feel like we’re veering toward a more conservative, heteronormative lens again. It’s definitely something to keep an eye on.

GLAAD: In the film, you talk about how television gave you a sense of safety and belonging growing up. Who was the first queer or queer-coded character who made you feel seen?

Regan: For me—and for a lot of people my age—it was Willow and Tara on Buffy. That relationship wasn’t perfect and didn’t end well, but for the time, it was more than we’d had before. Their relationship developed over time instead of being a short three-episode arc where a character tries being gay and then disappears.

GLAAD: I completely resonated with your choice to stay behind the camera. As a filmmaker myself, I get that instinct. But I loved your creative decision to use Lindy as your on-screen surrogate. What led you to that choice?

Regan: Lindy’s a fantastic actress and we’ve worked together on several projects over the years. We have a shorthand that made that decision a no-brainer.

GLAAD: Even though you’re not visually in much of the film, your voice and perspective are so present that it still feels fully autobiographical.

Regan: When I started the film, it was going to be Lindy’s story, told from her perspective. But then the pandemic hit, and I couldn’t keep filming with her. I realized that to stay true to the story, it had to come from me—because I hadn’t lived Lindy’s experience. Still, I didn’t want to be on camera, so it was this long internal battle. In the end, I only appear briefly, but once I accepted that it needed to be my story, things started to click into place. It flowed better after that. It becomes one more way the audience can connect to the film and the story I’m trying to tell.

GLAAD: It’s interesting you say that, because I think that’s very aligned with our work at GLAAD—trying to inform the broader culture, but in a way that doesn’t feel like a lecture. Because nobody likes being lectured to.

Regan: Yeah, that was the goal. Nobody wants to sit through a film and come out of the theatre after an hour and a half totally depressed. I knew I had to find a way to tell this story that would engage people—especially because I wanted it to be accessible. Queer audiences are already aware of this issue. So how do I speak to them while also making it something straight audiences can relate to?

And weirdly, it’s often straight audiences who come up to me after screenings saying, “I had no idea.” And I’m like—yeah, exactly! It still shocks me sometimes, but it makes sense. If you’re not in the community, you often just… don’t know. I’m in a queer bubble most of the time, and I have to remind myself that outside of that bubble, people aren’t having the same conversations.

If we went into this endeavor wagging our fingers and saying, “You’re killing us on screen,” people tune out. But if you make them laugh, if you draw them in emotionally, then they’re more open to hearing what you’re trying to say.

GLAAD: Right, and I think the way your film navigates that line is really smart. You took the emotional and neurological science of media consumption—like media psychology and the “transportation theory”—and used it to explain the trauma queer viewers often feel when they constantly see themselves die on screen. Can you expand on that?

Regan: Absolutely. The transportation theory is a concept in media psychology that describes how we, as viewers, are transported into a narrative. It’s not just a passive experience. Our brains process those stories as if they’re happening to us in real life. That’s why films and television can impact us so deeply—they activate the same emotional and cognitive processes.

So when queer viewers repeatedly see themselves die on screen, our brains aren’t just saying, “Oh, this is fiction.” We’re internalizing that trauma. It gets filed away in the same part of the brain as our real-world experiences. That’s why people cry at movies. That’s why you feel emotionally spent after watching something heavy. It’s not just because it’s “sad”—it’s because your body is reacting to it as if it actually happened.

GLAAD: That’s so powerful—and honestly validating. Because a lot of times queer people are told, “It’s just a movie, calm down.”

Regan: Exactly. And the science backs up that it’s not just a movie. It affects everyone. Straight people get emotional about fictional characters too—it’s just that when queer people do, it’s seen as overly sensitive or dramatic. But it’s the same psychological process.

GLAAD: And that’s part of the brilliance of the film—making that scientific angle accessible. Because Aiden Hirshfield, the researcher in the film, really breaks it down.

Regan: Oh, Aiden was amazing. I learned so much from them. And same with Sarah, the psychotherapist in the film. They both helped make all the science digestible. You can understand it on a gut level—“why do I feel this way?”—but then they give you the tools to name it, to understand it intellectually too.

GLAAD: And it’s not just about queer audiences—it’s about bridging communities. You’ve talked about wanting this film to reach straight audiences, which is so important when we think about building empathy and changing systems. How has that been going, especially on the festival circuit?

Regan: Honestly, the festival circuit has been incredible. We’ve done really well—we’ve screened all across North America, just screened in Australia, and we’re in Portugal this week. It’s been amazing.

But the reality is, most of those have been queer film festivals. And that’s not for lack of trying. We’ve submitted to a lot of mainstream, “non-queer” festivals, and the response has often been, “Oh, this is a gay movie”—and that’s the end of the conversation. They’re not interested. Which is frustrating—because even though the content is queer, I actually made this film for straight audiences as much as for queer ones. I wanted to explain something they might not be aware of.

GLAAD: That’s such a tough reality. We feel that too—sometimes it can feel like we’re just talking to each other. And we know that’s not where change happens. That’s why we focus on what we call the “movable middle”—people who might not be immersed in queer culture, but are open to learning.

Regan: Exactly. That’s the audience I want to reach. Because the truth is, straight people still hold the majority of the power in media—whether that’s in executive positions, funding, greenlighting projects. If they don’t understand the stakes, then we’re fighting a much steeper battle. That’s why I wanted this film to be entertaining and engaging. So people are laughing, maybe crying—but they’re learning. And hopefully, they leave with a better understanding of what’s really at play.

GLAAD: And especially now, that’s so urgent. We’re seeing the cultural pendulum swing back—DEI initiatives are being dismantled, there’s backlash against even the smallest bits of representation. It’s not just speculative. It’s happening.

Regan: Yeah. It’s wild. Lindy and I talk about the pendulum in the film—and over the years it took to make it, we saw it swing. Things were really bad. Then they got better. But now it’s swinging hard in the other direction. And it’s scary. What’s greenlit now, what gets made in the next few years—that will all be shaped by this current moment.

So yeah, it’s a little painful—but that’s why films like this matter. That’s why I want it to reach beyond the queer bubble. Because if we don’t educate and entertain the people outside our circle, we’re just preaching to the choir—and the people with power will continue making the same decisions that have led us here.

Bulletproof: A Lesbian’s Guide to Surviving the Plot is more than just a documentary. It’s a powerful statement, a call to arms, and a reminder of what’s at stake when we fail to honor our stories. It’s not just about queer characters living—they’re surviving, thriving, and showing the world that we will not be erased. This film is a reflection of every marginalized person who’s been told their stories don’t matter, and a promise that the fight for visibility, respect, and real representation is far from over.

As Regan and Lindy make clear, the battle is far from won, and the cultural pendulum is swinging in ways that threaten to undo the progress we’ve fought for. But films like Bulletproof serve as both a warning and a weapon in the ongoing struggle to ensure that our stories—our very existence—are seen, heard, and honored. It’s a reminder that we cannot afford to preach only to the choir, that we must fight to push beyond the bubble and challenge those who hold the power to shape the future of media.

Representation is not a luxury—it is a lifeline. It’s how we heal, how we grow, and how we ensure that future generations will see themselves reflected in the stories they consume. Bulletproof is an act of resilience, of pride, and of defiance. It is the vindication and validation that every lesbian character who has been marginalized, discarded, or killed on screen deserves. The story doesn’t end here—this is only the beginning. The fight for representation, visibility, and justice will continue, louder and more resolute than ever before.

To get a closer look at the magic and urgency of this film, be sure to check out the official trailer. Bulletproof will officially begin streaming in Canada this June, with additional festival screenings and updates to be announced on the film’s website. For more behind-the-scenes content and ongoing coverage, follow the film on Instagram and Facebook at @bulletproofdoc and director Regan Latimer at @thereganlatimer.