If Hollywood depictions and countless real-life stories with unhappy endings were the barometers by which Corey Perkins, 38, measured how his devout Christian mother, Patrice Manning, would react to his coming out as gay, the only scenario he could envision was one heavily influenced by religion that would lead to only one outcome—rejection. Yet, with unwavering courage, Perkins and his best friend, Phillip Williams, 36, also gay, embarked on a journey set in motion by Manning that defied their expectations.

Stepping into her usual role as the initiator of removing the elephant in the room, Manning said, “This will check off something that was on my bucket list,” at the start of GLAAD’s virtual conversation with Perkins, Williams, and Williams’ mother, Monica Jennings.

“I know nothing about the gay life,” Manning said. “When my son came out, I just had so many questions, and I wanted to be able to find some answers. I always wanted a safe space for that.”

Society rarely provides the affirming space Manning envisions for families of LGBTQ people, and even more so, the desire to have such in Black spaces is seldom discussed openly without anti-LGBTQ bias to derail progress.

“I [have] friends who wish they could have open dialogue with their mother like I have with mine,” Perkins said. “Because their mother is like, ‘I know you’re gay, but we don’t speak about it.”

This lack of open dialogue and support can be incredibly isolating and detrimental to LGBTQ people, underlining the importance of these actions in fostering acceptance and understanding within families.

“I think sometimes people are afraid of what they don’t have knowledge of,” Manning said as her son’s comments began to resonate, causing Manning to reflect on a phone call between her and her best friend, who also happens to be the grandmother of a lesbian granddaughter.

“‘I love my granddaughter, but I don’t want to be around that,'” Manning recalls her best friend saying.

“I just let her spill her truth, and as soon as she finished, I said, friend, I have something to tell you. I have a gay son. The conversation went totally silent,” she said.

Manning tells GLAAD that it wasn’t until after she revealed she is also the mother of a gay son that her best friend extended compassion.

For Jennings, the reaction of Manning’s best friend is, unfortunately, typical. It aligns perfectly with how she initially reacted to her son Phillip’s coming out, which was influenced by her Christian upbringing as the daughter of a minister.

“When he came out, everybody in the family embraced him more than I did because I was shocked,” Jennings said. “Everyone that I called when I first found out, the first thing they said was, ‘I love him, and you better not treat him any differently,'” she recalls.

“It was very tough because I grew up in the church,” Williams said. “So, I had heard all those [homophobic] things. It was indoctrinated in me, but I also said, “I have to live my life for myself.”

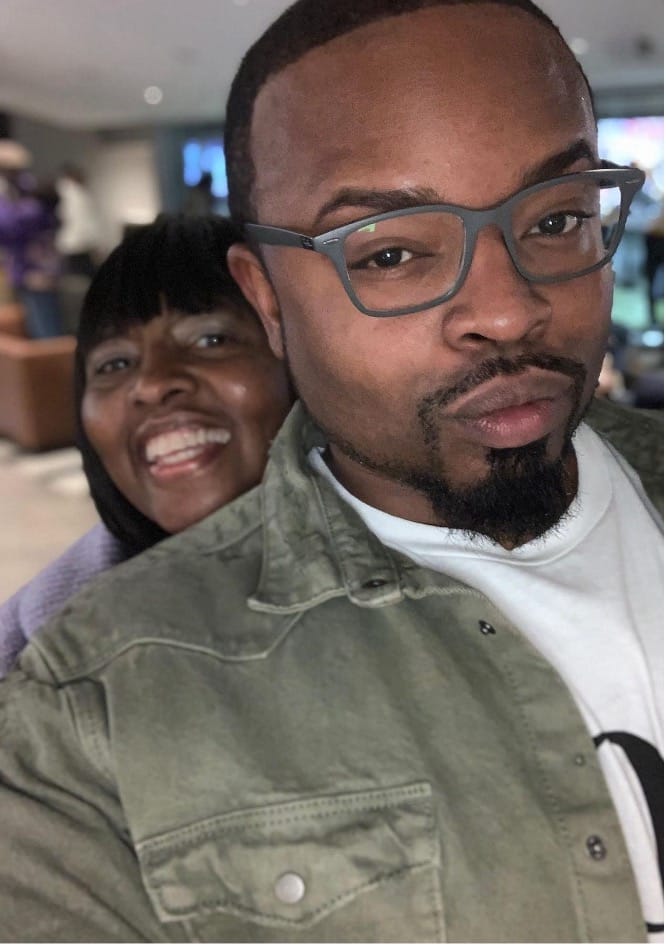

Williams, a real estate agent, and Perkins, a long-time Delta Air Lines employee based in Atlanta, have been friends for over a decade and consider themselves part of a chosen family. Their friendship laid the foundation for an unexpected bond between their mothers—providing support for two families reconciling the truth of their sons’ sexuality with their faith.

“People in the church need to realize God accepts all,” Jennings said before Manning began to describe her process of embracing her son Corey’s full humanity.

“Go with me quickly here,” Manning begins. “I’m carrying a baby boy in my belly. I’m feeding him. I’ve stopped drinking. I’m not smoking. I’m loving this baby that I’m carrying and nourishing inside of me. Once he comes out, this beautiful baby boy. I change his diaper. I prepare food for him. I breastfeed him. I dress him. Why would I have all that love, and then, when something changes or is different, I would abandon him? I would turn my back on him. No,” Manning said. “The only thing God said to me as a born-again Christian is [to] love him. That’s all I heard.”

My existence is resistance

Atlanta-based therapist and social worker Hakim Asadi, also present for the virtual conversation, tells GLAAD that queer people raised in traditional churches are often inaccurately taught they are unlovable as they are.

“You tell me my creator doesn’t love me because of this “lifestyle—” and I want to reframe “lifestyle” with life—this is my life,” Asadi said. “Lifestyle means there was a conscious choice in picking up this style because it’s trending or in style. That’s not it. The amount of oppression and shame people have to navigate—I don’t think that’s a choice in that way,” he added. “Do I choose my authenticity? One hundred percent.”

An out queer therapist focused on authenticity and healing for Black people, Asadi’s affirmation of Perkins and Williams’ intersecting identities in the presence of the women who birthed them was transformative.

“My existence is resistance,” Asadi said. “I don’t need to do anything. I just need to be. And so, by embracing my authenticity, I can navigate and walk through the world as myself. And if someone is willing and wants to know more, by all means, I don’t mind having a conversation, but what I won’t do is defend my existence,” Asadi said to nods of approval.

For both single men, romantic partnership is often a topic of conversation in Perkins and Williams’ friend group and among their mothers.

“I think Philip and I hope for it for each other because I’m still single, and he’s still single,” Jennings said through laughter. “I’ve already accepted that he said he didn’t want to have children—at least have a partner,” she added.

Like Williams, Perkins plans to remain child-free, except for his fur baby, a Schnauzer mix named Milan. Manning tells GLAAD that she initially struggled with the idea of praying for her son to find a same-sex partner.

“I had to come to a point that, yes, he deserves to be happy like everyone else,” Manning said.

“He deserves to have a life partner like everybody else. Why would he be excluded?”

The personal evolution of Jennings and Manning from traditionalists to LGBTQ allies and staunch defenders of their queer sons is a gift neither man takes for granted, especially Perkins, who is often sought after for advice from queer friends whose parents are not as accepting, allowing Manning to become a surrogate mother.

“They love that they can get the love from my mother, where it’s like—even though you’re not my son, I’m still going to give you that love,” Perkins said. “It just takes time. It doesn’t happen overnight for your relationship to be where it is with me and my mother. Because it was never an easy journey, but it’ll get there. You have to take baby steps.”

“I’m gonna love my boy,” Manning said. “And will turn into Mama Bear, and that’s about all of them, Phillip, too.”