This article first appeared in The Daily Yonder, a non-profit news organization covering rural America.

| This article contains references to suicide. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be reached by dialing 988, and the Crisis Text Line can be reached by texting HOME to 741741. |

It was spring break 2021. Jeans Corduroy was sitting in the passenger seat of his cousin’s black sedan. They were headed down a sunny highway back to Knoxville, Tennessee, from their family’s annual trip to Destin, Florida. “It was the first time I had freedom in six months — since everything had gone to shit,” said Jeans.

Jeans knew he had to tell someone while he had the chance, before he got back home to his parents who wouldn’t let Jeans use his phone in private. The black sedan was running out of highway. Jeans needed to make a decision. He picked up his phone, took a breath, and called one of the only adults he ever trusted, his high school teacher. Jeans told her everything.

Jeans wanted to get away from his parents as soon as he could. He felt like he was running out of time. During this period of his life, Jeans was deeply suicidal. He felt hopeless and helpless. He knew getting away wouldn’t be easy. He worried that it might be impossible. Jeans was 17-years-old. Still a minor. His birthday wasn’t for another nine months.

Jeans and his teacher came up with a plan. Do anything he can to just make it to age 18.

“Scared of My Own Identity”

I first met Jeans over Zoom. He was wearing a denim button-down shirt and a denim hat over his short brown hair that he’d been growing into a mullet. Being a denim-obsessed, former-farm-kid myself, I asked him if his shirt and hat had anything to do with his name.

Jeans’ mouth and the mustache that sat above it curled upward, and his eyes squinted from behind a pair of aviator eyeglasses. “I love wearing denim, but it’s got nothing to do with how I got my name,” he said, laughing.

Jeans’ full name is Edmond Jeans Corduroy. It’s a name entirely of his own choosing and one that he feels represents him like a charm. “Edmond,” a classy first name after some of his favorite painters. “Jeans,” a one-time autocorrect misspelling of his dead name (the name he was given at birth) that became a nickname among his childhood friend group. “Corduroy,” which started off as a funny idea, but ended up rolling off the tongue nicely. Most people just call him Jeans.

“And if you’re wondering,” Jeans said over Zoom as he pulled out a spiral-bound sketch book and a pen. “I like to draw when I talk, ’cause it’s easier to talk about topics when I’m doing something with my hands.”

I first learned about Jeans’ story when doing research for a project in my senior English seminar, in an article published by the Daily Yonder. The article briefly recounted Jeans’ experience as a transmasculine man in East Tennessee. In the article, Jeans told a reporter Skylar Baker-Jordan that he grew up scared of his own identity. I related to that.

I grew up in Ellis, Kansas, a small farming community in the western prairie, population 2,000. Generations of my family tended to the land and livestock in the heartland and called this place home. Due to my own queer identity as a gay man, my personal relationship with this home is indescribably complicated. At times, home is a place of boundless warmth, love, and support. But it can also be cold, lonely, and hateful.

When I encountered Jeans’ story, I felt seen. I asked myself, when was the last time I heard stories about a rural queer person — a story of hardship and triumph shared proudly in a publication, instead of sentiments of pity or judgment?

I wanted to meet Jeans — to learn more about his story, to learn more about my own, and to learn more about what it means to be queer in a time and place where large-scale legislative and cultural attacks are directed toward queer and trans youth in America.

Tennessee’s Anti-Queer Legislation

On March 2, Jeans was in class on what would have been an ordinary day. But then the news broke. The Tennessee General Assembly passed and Governor Bill Lee signed two bills that targeted the state’s LGBTQ+ community — Jeans’ community.

Jeans stood up, walked straight out of the classroom, and to the counselor’s office. He was mad that he couldn’t do anything about it. He was mad that none of his classmates or friends were as mad as he was.

The first bill prohibited gender-affirming care for minors who are transgender. The second bill prohibited drag performances in public spaces or wherever minors could be present. While proponents of the bill claimed that the measures were aimed to protect children, Jeans and other critics argued that the bill only hurt queer youth.

On March 31, USA Today reported that more than 650 anti-LGBTQ+ bills from 47 states had been introduced in the first three months of 2023. Rural communities in states with far-right state legislatures were among the hardest hit.

In rural spaces — where organized queer community groups, support groups, pride centers, and affirmative care options are less common — this anti-LGBTQ+ legislative movement makes bad situations worse.

A 2021 report from The Trevor Project found that 69% of rural youth in an online survey described the area where they lived as somewhat or very unaccepting of LGBTQ+ people. Only 19% of young people who said they lived in large cities said the same.

But determining the impact of rural settings on the lives of LGBTQ+ youth is difficult. In general, rural communities are culturally more conservative than urban ones, and queer folks may be less visible. This lack of visibility can contribute to an anti-queer social culture that could result in hate. But homophobia and transphobia are not inextricably linked with rural identity. It would be dangerous to make that assumption.

After all, Jeans and I both grew up in rural communities.

Jeans has lived near the Smoky Mountains of East Tennessee his whole life. He grew up near a little town called Dandridge, population 3,000.

Jeans lived with his mom, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins on what used to be a farm, Tucker Place Way. “That used to be owned by my grandfather,” Jeans shared. “He has since passed away, thank God.”

Jeans began to tell me about who his grandfather was but then stopped himself. “He also has a website,” Jeans said. “That might be helpful for this information. It’s called truthfromgod.com.” So I went to the website, as well as his grandfather’s Wikipedia entry to get the full story.

“Children of the Devil”

Jeans’ maternal grandfather is Dewey “Buddy” Tucker. Tucker was a pastor at Temple Memorial Baptist Church in Knoxville during the 1970s. According to a video posted on his website, Tucker had been visited by God, who shared with him the “real truths” of the Bible.

Tucker told his followers that God told him (and only him) that Jewish people were “Children of the Devil.”

“White western men are in fact God’s chosen people,” Tucker said in the video. “This was the key that unlocked the door into the storehouse of God’s vast and eternal truths.”

In reality, this was the key that Tucker and his followers used to justify antisemitic, racist, homophobic, and transphobic ideology. For years, Tucker preached this doctrine from the pulpit. The church’s outdoor lightbox often broadcasted religious and racial slurs to the streets of Knoxville.

In 1976, Tucker founded the National Emancipation of our White Seed, or N.E.W.S., a white supremacist movement that advocated for white separatism. During this time Tucker aligned himself with the Ku Klux Klan and other white nationalist leaders. In 1977, he spent nine months in jail for tax evasion and lost the Temple Memorial property.

As for Jeans, he tried to avoid his grandfather. He was terrified of him. But he couldn’t avoid his teachings. “Even as a child I wasn’t invested in the faith because none of it resonated with me,” Jeans said. “It all just sounded scary and hateful.”

No matter how disinterested Jeans was in his family’s religion, it already began to affect his relationship with his family, his friends, and his gender and sexuality.

Exploring Gender Identity

Jeans told me his queer story began at the end of seventh grade. Jeans and his mom packed up and left Dandridge. They moved in with his mother’s boyfriend, Eddie, who, like Jeans’ grandpa, was a preacher in Knoxville.

“Knoxville is like the city of East Tennessee,” Jeans told me. Knoxville is a medium-sized metropolitan area with a population of about 192,000 people. Jeans’ family still visited Dandridge often, which was only 30 minutes away.

Jeans transferred to Gresham Middle School in Knoxville, where he began to explore his gender identity. Like any other Gen Z’er, Jeans grew up online. He first encountered the idea of being queer on “Homestuck,” an enormous online comic that was started in 2009. The comic now has 8,000 pages of material. Though its plot is nonlinear, some of the stories within the comic contain queer characters.

“The majority of the fan base is queer,” Jeans told me. He learned about queerness when fans “shipped,” or rooted for, same-sex couples. “And then I fell down rabbit holes,” he told me.

The first trans figure Jeans encountered was Miles McKenna, a YouTube vlogger who documented his own transition. Jeans remembers when Miles came out as trans. “What?” he thought to himself. “You can do that?”

Though this exploration was an important step in Jeans’ story, he admitted that he wished he would’ve been exposed to queer culture by adults who could help filter out potential “smut” that can come up online.

“I could’ve had open conversations with people who had more wisdom than I did,” Jeans told me. “Who could police things that were genuinely dangerous, without policing things that were just scary to them.”

At school, Jeans felt safe around his friends. In this social bubble, he was able to experiment with his identity.

In his friend group, he tried out a different name and pronouns and presented more masculinely. When around the adults in his life, he felt forced to hide those parts of himself away.

“I got too comfortable,” Jeans said. “I stopped covering my tracks so well.”

At the beginning of 2017, Jeans’ older half-brother discovered that Jeans liked a trans group on Facebook and told Jeans’ parents. “The snitch!” Jeans exclaimed over Zoom.

His parents inspected his laptop and phone, where he had been chatting with friends and googling questions about gender and sexuality.

Then, his mom and Eddie began to interrogate Jeans, who tried to backtrack.

“I just heard about it and wanted to know more about it ’cause I didn’t understand it and nobody mentioned it to me before,” Jeans told them.

In April 2017, Jeans’ parents told him he would never step foot in Gresham Middle School again. He never finished the seventh grade. None of his friends from Gresham ever knew what happened. They wouldn’t hear a word about what happened to Jeans until 2022, when he was finally able to talk to them again.

The “Lesbian Era”

“They homeschooled me so I wouldn’t be trans,” Jeans explained. “That didn’t work out.” Jeans was enrolled in an online school that provided a “classical Christian education” to students in the East Tennessee region.

Jeans’ parents hoped he would make “better” friends and choices in this educational system. The school oversaw student progress and worked with a school cooperative that offered in-person classes once a week.

“I tried to be like ‘yes, I am a straight girl,’ but it wasn’t working,” Jeans told me. “The summer between seventh and eighth grade was one of the lowest points in my life.” He considered taking his own life. “Didn’t do that, thankfully, or we would not be doing this interview.”

Jeans survived that summer and started homeschooling in the fall. In eighth grade, Jeans explored again online, taking more care to cover his tracks this time around. Well if I’m a girl, he thought, I’m definitely attracted to girls, so there’s something going on here. Maybe I’m a lesbian.

But Rachael and Eddie caught wind of his exploration and clamped down on him once again. He tried to get back in their good graces.

He and his mom got a membership at the gym. He got a boyfriend. He did a lot of chores around the house to try and make nice. “But none of it worked,” Jeans said. “It just made me hate my life and myself.”

Jeans started spending a lot of time with a friend from school, Nat, who quickly became one of his best friends. “At this point [Nat] was very much a straight Christian conservative girl,” Jeans laughed. “None of that is true now.”

Nat and Jeans dreamed of their future lives. They joked about forming a band called “The Plant People.”

“Jeans was gonna be Sunflower, and I was gonna be Fern,” Nat told me in a phone interview. “I feel like that’s such a good analogy for both of our personalities”

Throughout his freshman and sophomore years of high school, Jeans fully embraced his self-proclaimed “lesbian era.” He and his boyfriend had broken up, and he started dating a girl, his friend Bick. Jeans felt it would be easier to identify as a lesbian, rather than trans.

But when Jeans’ family found out about his “lesbian era,” his world tumbled down again. No cell phone. No laptop. No privacy.

“One of My Biggest Regrets”

Fast forward to September 2020 — Jeans supposes it was sometime near the autumnal equinox. It was the second most important day of his life, so far.

Jeans finally gained back some freedom. He was finally allowed to use his cell phone. At last, he could use his laptop (as long as his bedroom door was open). He could also sleep with the bedroom door closed. He was glad to have some hints of privacy again.

With that freedom, Jeans invited Nat and a few other friends to brunch at LuLu’s Tea Room in Knoxville. LuLu’s offered the kind of cozy, friendly atmosphere that you might expect from East Tennessee. Plus, Jeans appreciated how welcoming LuLu’s was to all sorts of different folks. Unconditional Southern charm, if you will.

The night before the brunch, his first outing with friends in weeks, Jeans felt incredibly anxious and didn’t sleep a wink. “Everything was getting to me,” he told me. “Hiding who I was, the terror of being found out, everything was weighing on me.”

It was 5 in the morning. Jeans took his phone with him into the bathroom, which he wasn’t allowed to do. “That is one of my biggest regrets of it all,” he said. “It ruined me.”

He was communicating with his high school teacher. Remember her? One of the few trusted adults in Jeans’ life. They were messaging over Instagram. She didn’t know a lot about what Jeans had been through, and he was trying to be vague.

“She was trying to be supportive in any way she could,” Jeans recalls. “She was a safe space and I trusted her a lot.”

At one point during their conversation in the bathroom, his teacher sent a message to help calm Jeans down. Jeans doesn’t remember exactly what the message said, but he remembers that it was funny. He let out a laugh as he finished up in the bathroom, put his phone in his pocket, washed his hands, and opened up the bathroom door.

Eddie stood in the doorway, his presence towered over Jeans.“What’s so funny in the bathroom?” Eddie asked.

All the blood rushed out of Jean’s face and a pit grew in his stomach. He lied, trying to cover his tracks, but it didn’t work. Jeans’ phone was already in Eddie’s hand. Jeans rushed to his bedroom, opened his laptop, and frantically deleted anything that related to his queerness.

“It’s funny,” Jeans told me. “Out of everything that Eddie could have found. It wasn’t any of the messages I’d sent. It wasn’t any of the notes in my notes app. It wasn’t any of the things I’d been looking at on YouTube or Google.”

It was an account that Jeans followed on Instagram. One of those circa 2020 aesthetic affirmations pages. The kind that says something like “POV: You’re a Queer Older Brother” and shows a collage of cropped pants, a Phoebe Bridgers album, and a Pontiac Grand Prix.

Eddie walked into Jeans’ room, shoved the phone in front of his face, and said “Explain this.”

“You know what?” Jeans said. “I’m gay.”

Jeans spent most of that day on the living room couch, surrounded by stacks of plastic storage tubs filled with clothes that his mom would buy and resell online. Jeans remembers sitting on the couch for hours, his skin against the velvety velour of the cushions.

“I was looking around at all those tubs — they were numbered — and I was just trying to notice patterns in the numbers and do anything to distract myself,” Jeans said. “I was trying so hard to be anywhere else.”

“My mom, she just shut down from all of it,” Jeans told me. “She was grappling in her brain with what felt like the death of her child — even though I was right there.”

Eddie took it worse than Rachael, which surprised Jeans. He was upset that Jeans had broken his trust, yet again. Jeans hoped that maybe Eddie would disown him.

It was impossible for Jeans to keep track of how much time passed as he sat counting crates. There weren’t many windows in the house, and any natural light that was creeping through was blocked out to make sure none of the clothing faded.

“At one point,” Jeans said. “I promised them both that I was going to kill myself.”

Eddie said nothing.

“OK,” said Rachael.

Six Weeks in Solitude

For the next six weeks, Jeans disappeared from every aspect of his life outside the house. His parents took his phone and his laptop, so he couldn’t search the web or communicate with friends. He stopped doing his homework; one, because he didn’t have access to his computer and two, because of his overwhelming depression. His friends helped him out by emailing his teachers from his email address.

If he wanted to watch TV, Jeans would have to watch it in his mom’s room, under adult supervision. TV allowed Jeans to escape from reality. He watched HermitCraft on YouTube, Avatar the Last Airbender three times all the way through, and the theatrical version of Little Shop of Horrors seven times in a week.

Jeans was not allowed to go into his room, not even to sleep. For the next six weeks, Jeans had to sleep next to his mom in her room, and Eddie slept on the couch. “So now this small house is even smaller,” Jeans said. “My one safe space — my bedroom — exploded into ash. ‘No more. Can’t have it no more.’”

At the end of six weeks, Jeans’ parents started to loosen up their grip again, after receiving worried emails from Jeans’ school. Jeans started doing his homework again, but he still wouldn’t have contact with the outside.

In November 2020, Jeans’ maternal grandma passed away. The family spent a lot of time in Dandridge during this period. Rachael and Eddie used her sickness and death as an excuse for Jeans’ absence from outside life.

Spring Break, Boba, a Normal Day in June

Then came March 2021. After seven months of solitude, Jeans’ parents granted him limited access to his phone. He was only allowed to contact immediate family. Much of the data on his phone was scrubbed. All of his apps were deleted, and the contact names were removed. To repopulate his contact book, Jeans cold-called every number in his phone and recited the following message: “Hi. This is [dead name]. I’m not dead. I’m OK. I’m not gay.”

For spring break that year, Jeans and his family took a trip to Destin, Florida. He was excited to get out of the house and away from Eddie, who stayed back in Knoxville.

Jeans had a blast during the trip. He rode down in his cousin’s black sedan, separate from the rest of his family, and experienced rare freedom during the trip.

It was on the way back to Knoxville that Jeans called his high school teacher. “I can’t go back home,” he told her. “I need out.”

“You have me in your corner,” she told Jeans. “It’s gonna be OK, you need to hang in there.”

And so they came up with the plan: Make it to age 18.

…

Then came June. Jeans, Nat, and his teacher coordinated to meet at a local Boba shop, called Hey Bear, in Knoxville. They wanted to come up with a contingency, in case Jeans felt it impossible to make it to 18.

Jeans, who at this point was allowed to drive alone, met his teacher and Nat in the parking lot and walked into Hey Bear together. Jeans ordered the brown sugar milk tea.

The group huddled around a table. They made some additions to the plan. Jeans’ teacher had a friend at the state Department of Children Services who told her that a local Kroger — the one right next to the Target closest to Jeans’ family — was a registered safe house, a place where people who are afraid can go to seek help. This was Jeans’ contingency. They finished their Boba and went their separate ways.

…

Later that month, Jeans and Nat spent a sunny summer day together, driving all over Knoxville. They went to their favorite restaurant, spent the afternoon wandering around the mall, and were cruising around while jamming to music.

Text from Mom: Eddie and I are out doing shipping today, so you’ll have the house to yourself.

Jeans gripped the steering wheel with white knuckles and began to sweat. “My heart was racing, just thinking, ‘Please don’t let his gun be there.’ ”

The last time Jeans was home alone was when he was 13 years old, the first time he almost committed suicide. He parked the car, went into the house, and saw Eddie’s gun in its typical spot.

“I came this close to taking the opportunity,” Jeans said as he held up two pinched fingers on our Zoom call.

“Well now I have to do fucking something,” he thought. “‘Cause if I get another opportunity, I’m taking it.”

At the Bottom of Everything

It was July 1, 2021. The biggest day in Jeans’ life so far. Jeans and his family were cleaning out some of his grandma’s old stuff. They had loads of her things sitting around the house to be sorted and donated.

“Hey, do you want to go to Goodwill with me?” asked Rachael. “After we go to Goodwill, I want to go to Target and grab some groceries, too.”

“This is my chance,” Jeans told himself. “This is my way out. Today’s the day.”

During our interview, Jeans stood up and grabbed a colorful backpack that was sitting on his dresser. It was an Animal Crossing bag, covered in cartoon apples, cherries, oranges, and other fruits. Cartoon characters poked out from behind a banana there, and a pear here. The bag was trimmed with red zippers and red straps.

“Other than the clothes I was wearing,” he said as he held the bag up over Zoom. “This, and the things in it, were all I took with me when I left home that morning.

Jeans focused on the essentials: Social Security card, birth certificate, driver’s license. Next, were other necessaries: his sketchbook and a Dungeons and Dragons binder. The binder itself wasn’t D&D branded. “Cute puppies on the outside, D&D murder plans on the inside,” Jeans told me as he showed me the binder. Finally, Jeans grabbed whatever else could fit inside his small pack, extra underwear, a pair of shorts, a 3D pen project his cousin Murphy gave him, and other things that were small, but important.

“Let’s get going,” Rachael called.

Jeans’ heart raced faster as they made their way from home, to Goodwill, to Target. He was terrified, excited, and incredibly anxious. “She could probably feel the anxiety coming off of me,” Jeans told me.

The sun shined down on the hot black pavement as Jeans and his mom got out of the vehicle and began to walk towards the Target entrance.

“Hey Mom, I’m kinda hungry,” Jeans said. “You think I can go to Kroger and get some sushi?”

“Sure,” she said.

Jeans started toward the Kroger. He was sweating bullets, and the summer sun wasn’t helping. “It was the highest anxiety I’ve ever felt in my life, to this day.”

He entered the Kroger and saw an elderly woman arranging bouquets in the floral department and told her he needed help. She called one of her supervisors, who brought Jeans to the customer service area. Jeans sat behind the desk and waited, looking at all of the faces that passed by, mortified that one of them might be his mother. He waited there for what he said felt like 80,000 years. “But it was probably only like 25 minutes,” he told me.

Jeans took out his phone and sent one last text. It was to his younger cousins Murphy and David, the only family he still misses today.

He sent them a lyric from the song “At the Bottom of Everything” by Bright Eyes. “I love you very very very very very very very much.”

He turned off the phone, so his family couldn’t track his location, and gave it to the people at lost and found.

Soon after, a police officer, a young woman in her mid-20s, came and spoke with Jeans. She brought him in and put him in the back of her police car as Jeans explained his situation. The cop mentioned something about having a girlfriend, which helped settle Jeans’ nerves. Then she went to find his mom.

“Your mom wants to talk to you,” she said to Jeans.

“I would not like to talk to her,” Jeans said. And he never did.

So Jeans sat in the back of the officer’s car, while the cop spoke to Rachael on the outside. Eventually, Eddie showed up to the scene and joined in the conversation. Jeans couldn’t hear anything but muffled voices through the car doors, which he was very thankful for. After nearly an hour, the cop returned.

“Unfortunately, since you’re a minor,” she said. “I’m afraid you’re gonna have to abide by your parent’s wishes and go back home.”

“If you make me go back to that house,” Jeans responded. “I am going to kill myself.”

“That’s a very serious claim,” she said in a voice that was serious and calm. “Would you like me to call an ambulance?”

“Yes!” Jeans exclaimed. “If you send me back there I’m going to kill myself. Please, God.”

Jeans waited for over an hour for the ambulance to arrive. His parents stood outside the entire time, looking into the back window at Jeans. Rachael was crying. Eddie was furious. Jeans kept looking forward, not flinching a bit.

“I felt kind of safe because [the car] was locked and nobody could get in.” Jeans told me. “It was not comfortable, and I don’t like police, but in that moment I was protected.”

The ambulance came. They put Jeans onto a stretcher and loaded him up in the back of an ambulance. As the back doors of the ambulance closed on Jeans’ past, and the vehicle drove away from his parents, Jeans began to feel safe.

“Maybe things are gonna be kind of OK,” he thought.

Jeans was driven to the emergency room by a trans woman named Tiger. “I was awestruck,” Jeans said. “She was tall and strong. Her auburn hair was tied back to reveal two trans pride earrings.”

“It Wasn’t Just Me”

Jeans arrived at the North Knoxville Medical Center at around 5 p.m. on July 1. Because of Covid, Jeans and the other patients experiencing suicidal thoughts stayed in beds in the hospital’s hallway.

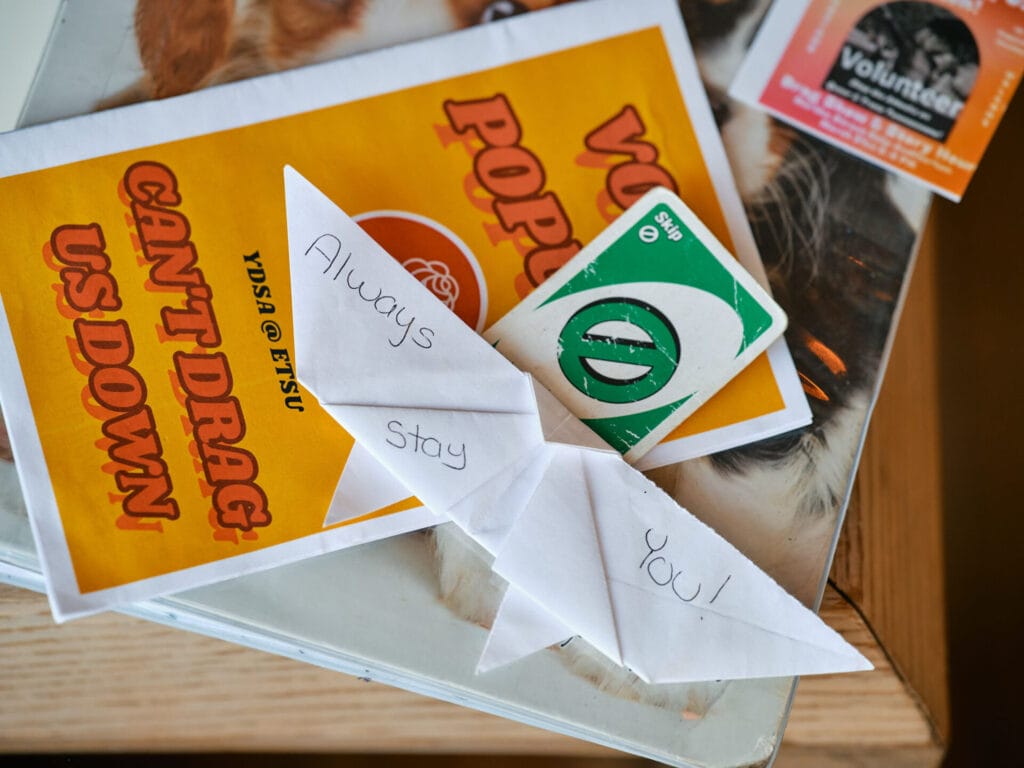

Jeans found comfort in the hospital, where staff affirmed his chosen name and pronouns. Jeans remembers one nurse tech, with a rainbow tattoo. She gave Jeans an origami butterfly, with a message written on its wing: Always stay you.

“It wasn’t just me,” Jeans said, recounting all of the queer people he’d met during his recovery. “This was the first time that I’d experienced queer people in real life.”

In the early morning of July 6, Jeans was awoken by a police officer, was handcuffed, and put in the back of a police car to be transferred to Rolling Hills Mental Hospital in Franklin, Tennessee.

Jeans told me that though the conditions of his transfer were procedural, they were also cold and criminalizing. Despite this, Jeans felt comforted in this moment. He knew he was headed in the right direction. As a warm beam of light shined down on his face, he fell asleep and napped through the four-hour drive.

“Finally Over”

Jeans spent 81 days in the Rolling Hills Mental Hospital. From the moment Jeans settled into the facility, away from things back in Knoxville, he felt more comfortable and less suicidal than he’d been in years.

The better he felt, the more his caretakers pushed for him to return home. And whenever his caretakers brought up the idea of going home, the worse he felt.

“If you send me home, I will still kill myself,” Jeans told them. “That’s still the thing, I haven’t changed my mind on that.”

After a couple of weeks, Jeans attended his first family session with his parents over the phone.

“I was trying so hard to build a bridge between me and my mom,” Jeans told me. “They spent almost the entire time just belittling me and telling me every way that I’d hurt them.”

I reached out to Rachael for comment, but she chose not to respond to my inquiry.

They had another family session a couple of weeks later. Jeans went into the session feeling hopeful. “No one wants to lose their family, to start their life over from scratch,” he told me. “That [session] was somehow worse.”

After the call, Jeans stormed into his room and ripped down a painting he’d made in the hospital’s art therapy program. Streaks of jet black paint depicted a young Jeans, chained to the ground, with his parents looming over him.

He paced back and forth, ripping the paper into shreds, smaller and smaller until he, Rachael, Eddie, and all the despair became hundreds of tiny, pinky-sized pieces. Jeans fell to his knees, onto the paper-covered floor and begged God for forgiveness.

Eighty-one days after he was first admitted into Rolling Hills, Jeans’ social worker, Shelley Campbell, interrupted his group therapy session. Jeans described Shelley as a “scary” middle-aged woman — the kind that can get shit done. She fought for Jeans to be placed under state custody. Shelley brought Jeans to a private room and announced the news.

“We found someone for you,” she said. “You’re leaving today. You’re going home!”

Later that afternoon, as Jeans sat in his room, packing his Animal Crossing bag, he thought to himself: “It’s over. I’m free. After all these years of torment and hell, it’s over. It’s finally over.”

A New Home

Jeans left Rolling Hills that evening and rode with this DCS worker, Jennifer Vowel, back to Knoxville, where his foster parents were living. As they entered a little suburban neighborhood, Jeans watched the houses roll by, wondering which house Vowel would pull into. The car finally settled to a stop.

Jeans pressed his face up against the glass and searched through the moonlight to find any clues about his new family. He remembers stereotyping the house.

There was a big truck in the driveway. “Oh no, not this,” Jeans thought.

He looked through the window of the house and saw a buff, blond man with a choppy haircut. “No, no, this doesn’t feel right,” he thought.

“I make mistakes too, you know,” Jeans told me as he started to laugh. “It turns out that that ‘man’ was really just a butch lesbian. Who are my foster parents, but a lesbian couple?”

Rachel and Sabrina Ponder fostered Jeans through his entire senior year. Rachel, the blond, is a triathlete who has completed an Ironman: a two-and-a-half mile swim, a 115-mile bike, and then a marathon. All back to back. She’s also the head of the Criminology Department at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. Sabrina works as an anesthetic nurse at the University of Tennessee Medical Center in Knoxville.

In the next week, Jeans got a new phone, a haircut, and enrolled in public school.

“I finally had space to let my identity grow and shift and change and I’m now a trans guy,” Jeans told me. “They were so incredibly supportive of me. It felt like finally everything was worth it and everything was gonna be OK.”

For the next year, Jeans spent weekends in Chattanooga watching Iron Man races, and every Friday evening eating ice cream and watching the latest episode of The Great British Bake Off.

“Can’t Drag Us Down”

In autumn of 2022, Jeans started college at East Tennessee State University, where he studies digital media. These days he checks in with Rachel and Sabrina several times a month.

“[Living with them] was lovely and now I’m thriving.” Jeans said. “Their goal was to get me to college and to get me stable, so I’m not really relying on them for anything. They were a good part of my journey.”

Jeans works three jobs to provide for himself. He attends church weekly at UKIRK, a queer-accepting, campus church. “Which is crazy, but I love it,” Jeans laughed. “Our minister is non-binary and everyone who goes there is either queer, trans, or both.” At UKIRK, Jeans has been able to reconstruct his own view of religion.

Jeans is also heavily involved in campus politics as a member of the Young Democratic Socialists of America (YDSA). When news of anti-queer legislation broke, the group’s leadership began to plan a protest event.

They decided to organize a family-friendly drag show to be held on March 31, 2023. One day before the anti-drag law went into effect. They called the event “Can’t Drag Us Down.”

Despite numerous attempts by ETSU to tamp down the event, including last-minute venue changes and banning minors from attendance, the event forged on.

The show featured drag performers and speakers. Over 900 people attended the event including state and local representatives. Presidential Candidate Marianne Williamson also attended. Can’t Drag Us Down helped raise almost $3,000 in donations that went directly towards the Johnson City Pride Center and the performing drag queens.

“It was probably one of the last public drag shows in the state before the ban took place,” Jeans said.

After the show, members of the YDSA gathered at Mid City Grill in downtown Johnson City to celebrate.

“There’s community built in the impoverished. That’s the only way we’ll survive is when we have this system that supports everyone,” Jeans said. “And that’s incredibly rich in Appalachia because we want to help each other out. Otherwise, we’ll die out.”

“That moment felt religious,” Jeans said. “That is why I ran away. That is what this is all about.”

Lane Wendell Fischer grew up as a gay man on his family’s cattle ranch in rural Western Kansas. He’s a recent graduate of Yale University and writes about education and culture for The Daily Yonder, a non-profit news organization covering rural America.