“I just needed someone to come and tell me that it was OK, that there was nothing wrong with me. And eventually, I got that message. It just took years.”

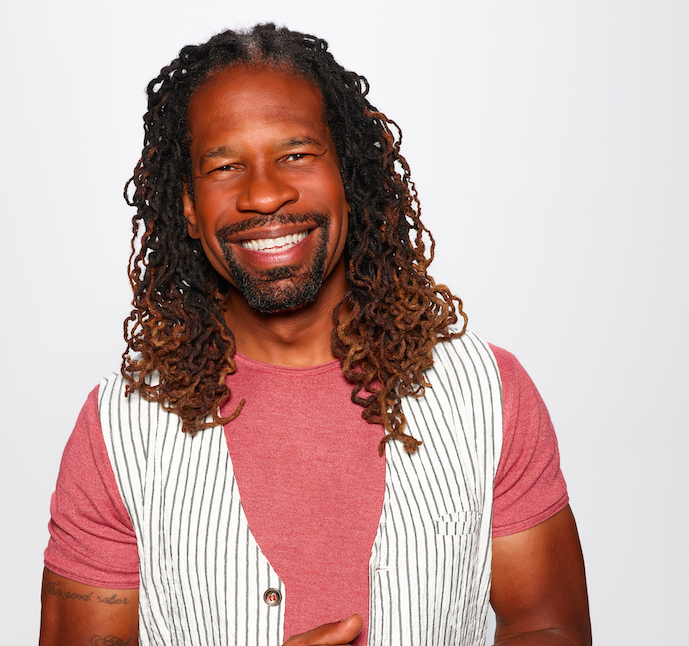

LZ Granderson was one of the cohosts of SportsNation on ESPN when he married his husband, Steve Huesing, and while it seems rather unextraordinary today, it was groundbreaking to have an ESPN host, a Black gay man, share pictures and stories on air about his wedding to another man.

“I really don’t recall anyone else at ESPN who married their same-sex partner having those pictures up on the network prior to that day,” Granderson says. “I had to believe that there was a queer kid out there working in a bar, maybe not even having the volume on, glancing up and seeing that on ESPN. I know what that would’ve done for me.”

As more athletes come out of the closet in recent years — Carl Nassib is the most recent high-profile example in the NFL — Granderson notes a real change in how these stories are covered. Seemingly gone are the questions that Granderson encountered at the start of his career about what would happen if a gay man was ever to enter a locker room. The vast majority of the coverage by those at ESPN and other mainstream outlets when it comes to queer athletes is celebratory, especially when it comes to the WNBA and the Women’s National Soccer Team.

Granderson talks on this week’s LGBTQ&A podcast about this recent evolution in coverage around LGBTQ+ athletes, his time at ESPN where he says he “vacillated between being tolerated and being ignored,” and the new season of his podcast, Life Out Loud (new episodes come out every Thursday).

You can listen to LZ Granderson on LGBTQ&A and read excerpts below.

Jeffrey Masters: You’ve said that you had trouble getting hired to cover sports because people said that they couldn’t send a gay man into locker rooms. Once you were hired, how much did your sexuality affect where they sent you and what you were assigned?

LZ Granderson: I definitely have felt for a big chunk of my career that the opportunities that I was qualified for or expressed interest in that I did not get, a lot of that particularly early on were attributed to me being openly gay.

I also happen to be Black, and so you don’t know if what you are being subjected to is based upon homophobia or if it’s based upon racism or it’s based upon both. I could point to statistics and go, “Well, obviously there weren’t a lot of openly gay journalists period during 1995.” But I also can point to statistics to support that there weren’t a lot of Black journalists in certain positions in this country, particularly nationally in terms of sportswriters or hosting late-night television or hosting the evening news, but certainly, I think we can all agree that history has shown that whether you’re LGBTQ or a racial minority, there are obstacles in this country that could hold your career back.

JM: You married your husband while at ESPN. How was your marriage treated and acknowledged?

LG: I was really fortunate in the sense that by the time marriage equality had passed, Disney, which owns ESPN and ABC, had already set a culture in which LGBTQ+ acceptance was an essential aspect of the culture.

And so by the time I got married, not only was I fortunate not to have to worry about losing my job, which unfortunately, a lot of Americans still do today in parts of the country, but the show that I was cohosting at the time, SportsNation, showed my wedding pictures. And we talked about my marriage on air.

I don’t keep track of the first blah, blah, blah. It’s not really something I consume myself with, but I really don’t recall anyone else at ESPN who married their same-sex partner having those pictures up on the network prior to that day.

And so that day did mean a lot to me, not just because it was celebrating my marriage, which was obviously a really, really awesome and amazing thing to do, but just that I had to believe that there was a queer kid out there working in a bar, maybe not even having the volume on, glancing up and seeing that on ESPN. I know what that would’ve done for me, so I’m just going to assume that may have done something for someone else in places in the country that doesn’t have the same level of acceptance that we’ve grown accustomed to in larger parts of the world.

JM: And yet when you left ESPN, you wrote that you “vacillated between being tolerated and being ignored” while you were there.

Oh, absolutely. It was like, “Yeah, you’re here, and yeah, we’ll utilize you, but we really don’t see you as a part of us sports society, sports culture, sports fandom. So while we’ll utilize you for certain things because you’re talented and that’s your job description, we won’t utilize you in the same way we would people that we think really represent who we are trying to reach.”

And I saw tons of examples of that. I was really fortunate to host an online show back in the day called LZ’s Cafe. And while I was absolutely thrilled to have had that opportunity, I also know that our budget was so shitty that at moments I had to hire freelance reporters who had cameras that had masking tape and duct tape holding them up. And I wasn’t talking to nobodies. I distinctly remember interviewing Kevin Garnett and the lens from the camera popped out from the duct tape that was helping to hold it together. But that was all that we can afford on my show.

But you fast-forward not too long ago and I see other colleagues who have now developed similar shows that get support. They have budgets. They’re not worried that the fucking lens is going to fall out of the camera as they’re interviewing a high-profile athlete. Those are the are little things that I’m talking about. Never, ever having anyone hired to do my hair, for instance, but I get to see every single one of my other colleagues sit in that chair and get their hair done along with their makeup because in all the years that I covered Wimbledon in London, they never hired anyone to actually do natural Black hair.

Shit like that. You get the hints. You know when you’re being celebrated and embraced versus being tolerated, so I had been used to, to a certain point, being tolerated as an openly gay person, so my armor was thick and I had a nice and shiny sword and I went to battle every single day for the most part for 17 years, and then one day I woke up and I just thought, I want to fight for something else now, and that’s why I left.

JM: Almost every pro sport in recent years has had a big athlete come out. Carl Nassib in the NFL was the most recent, in 2021. Looking at Jason Collins, who came out in the NBA in 2013, there’s been a bit more time since then and we can see the impact there. We haven’t seen a cascade of queer people coming out or joining the league. Would you have thought it would have led to more?

LG: No, I did not. I think there are a lot of things at play here. There’s an assumption from some people that there aren’t any other people, gay men specifically, in the big four sports who are gay. So it’s like, “There aren’t any others” is the one perspective.

And the other perspective is that there are tons more, and they’re too ashamed to come out or too fearful to come out. And I would argue that the truth is probably somewhere in the middle, that maybe part of the reason why this hasn’t been as a cascade of players coming out is because there isn’t one to be had. That’s not suggesting that there aren’t a lot more, but how many more do you need to come out before you’re satisfied?

JM: If these few coming out doesn’t automatically make it a welcoming environment, what will it take? What does is needed to create more change?

LG: Well, I would like to think that there have been some leagues — you mentioned Jason Collins in the NBA — that are a little bit more ahead than other leagues. When I think about those eight years between Jason Collins and Carl … when Jason came out, I was on ESPN and I got into this huge fight that went viral, unfortunately, with my colleague, because we started talking about homosexuality and if it’s a sin and the Bible and it was really, really messy and not good.

And there was a lot of other pushback from other athletes. That was the environment then.

I don’t think we really saw that in 2021. If anything, what we saw was, I believe, a lot of progress being made by the media that covered these events, that cover these sports and these stories, because a lot of the way that this story has been perceived is the way that has been constructed by the media that covers these sports and these coming-out stories. And so I think that you did not see NFL beat reporters and mainstream media in other aspects continually ask players about how they feel about having a gay guy in the showers and stupid-ass questions like that.

Whereas back when Jason Collins came out, you were still debating about the shower. So I think there’s been a lot of progress that has been made and in that progress, hopefully, comes a culture in which, if someone is queer and if someone does feel comfortable coming out, that they feel and know that they will be supported by those leagues and by their fellow athletes. I think Carl’s story is one example that we can build on, but we shouldn’t overlook what the WNBA has been doing in this space for years. We shouldn’t overlook what tennis has been doing in this space for decades, which is when those as athletes come out, finding ways to not just tolerate them but to celebrate them, recognizing how difficult it is for those athletes to do that.

And it’s really why I wanted to do the podcast, Life Out Loud, because I know that there are still so many stories out there that haven’t been told.

You can listen to the full podcast interview with LZ on Apple Podcasts.

LGBTQ&A is a weekly LGBTQ+ interview podcast hosted by Jeffrey Masters. Past guests include Pete Buttigieg, Laverne Cox, Roxane Gay, and Miss Major Griffin Gracy.

New episodes come out every Tuesday.