Chicago was an appropriate host for the 2024 Community Center Leadership Summit, where the national association of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender community centers convened hundreds of nonprofit leaders throughout the nation. Illinois, sandwiched within the midwest, a region most certain to inform the direction of the Presidency on November 5, became a week-long hub for resource sharing, and community building.

At the Summit, the GLAAD Media Institute (GMI) – GLAAD’s research, consulting and training division of the organization – held two coaching sessions to over 100 summit attendees, designed to equip community center leaders to cultivate better relationships with local media in their regions and also pitch stories more effectively to local news. The coaching sessions were followed by an on-the-record Q&A session together. Those who complete GMI coaching sessions are immediately deemed GLAAD Media Institute Alumni, prepared to engage with media and local leaders using GLAAD research and best practices.

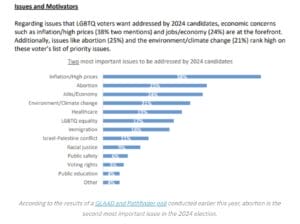

Major issues presented by nonprofit leaders in Vermont, Illinois, and California ahead of the 2024 election ranged from equity, bodily autonomy, housing, and climate change. These overlapping issues, not always recognized LGBTQ issues, are in line with GLAAD research outlining top concerns among LGBTQ voters in 2024.

GLAAD and Pathfinder data shows that LGBTQ voter concerns range from: inflation and high prices to abortion (bodily autonomy), environment and climate change, healthcare and LGBTQ equality, and other concerns.

Thea Gay, a CenterLink volunteer, whose mother also works with CenterLink’s membership team, moved from Florida to Chicago three months ago. The advocate says the “extremely contentious environment” of Florida caused her to move. She is seeking safety, respect, and the choice to just exist as a Black, queer woman in the United States of America.

“I want to make sure that I’m in spaces where I feel seen and respected,” Gay told GLAAD. “I don’t [want] to hide parts of myself, but also, part of that transition [to Illinois], included finding ways in which I could fight back against book bans and ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bills in an environment where I feel safer.”

While recent data from Trevor Project states that 45% of transgender and nonbinary youth have considered leaving their state, a similar percentage of parents (40%) in Florida considered the same for their LGBTQ children, according to the Williams Institute.

However, it isn’t just about authentically and safely being able to be herself in advocacy work and in life, Gay is also on the front lines of environmental justice. Something she will continue to fight for no matter who wins the election.

“I work in the environmental justice space, and I think it’s really important to understand how interconnected our movements are, so being in this LGBTQ+ advocacy space, not only am I able to see myself, but I am also able to see the ways that I can plug in and bring what I am learning here into my issue area,” Gay continued.

Much of the LGBTQ community live in regions of the country disproportionately affected by climate change. Making quality of life, bodily autonomy, and affordable housing difficult to achieve.

In fact, for Gay, living in a city like Chicago allows for her to focus on a greater mission of change for LGBTQ people and others, rather than fighting for baseline protective LGBTQ laws that might distract from overarching issues such as climate change and housing. This, consequently, is an adjustment from Florida where climate disaster and anti-LGBTQ discrimination can be overbearing for young activists.

While most Floridians do not support anti-LGBTQ laws, stigma and discrimination continue. Polls show that nearly 75% of Floridians support fully inclusive laws to protect LGBTQ people from discrimination, according to Equality Florida. Yet, the lack of anti-discrimination policy increases stigma, and harm against the community, according to GLAAD’s 2024 Accelerating Acceptance data.

With this in mind, pro-LGBTQ politicians in Florida have passed more local nondiscrimination policies than any other state in the country. Additionally, every single policy includes gender identity and sexual orientation protections. Those protections now cover 60% of Floridians in the third largest state in the country, according to Equality Florida’s website.

For people like Mimi Demissew of California, LGBTQ protections aren’t the problem in their state, but equity, affordable housing, and bodily autonomy are.

Demissew, is the executive director of Our Family Coalition in San Francisco – an organization that works with building equity for LGBTQ families – and finds even California’s most progressive LGBTQ protections haven’t expanded access to health insurance for family formation until very recently.

View this post on Instagram

The law SB729, also known as “health care coverage: treatment for infertility and fertility services,” broadens access to infertility treatment with a new definition. The law now defines infertility by need for medical intervention rather than by sexual activity. What the change allows is for LGBTQ families, including trans single parents, to use health insurance for fertility treatments, which helps with costs, says Demissew.

“California is a very difficult state to live in if you are a working family,” Demissew told GLAAD. “The communities [Our Family Coalition] currently serve are having a difficult time finding affordable housing, having their wages high enough to afford them [a quality life] to live.”

For instance, the proportion of LGBTQ people earning less than $24,000 per year in California’s North and Mountain region is comparable to the rate in the Southern (33%) and Midwest (35%) regions of the US, according to the Williams Institute. Therefore, affording to start a family as LGBTQ people in the area can come at a high cost, says Demissew. In San Francisco alone, half of the houseless population is LGBTQ youth, according to a San Francisco’s LGBT Center article.

Like Gay’s family – but for different reasons – Demissew finds families are leaving San Francisco, or California, for more affordable cities and states that grant LGBTQ people “access to equality.”

Consequently, Demissew hopes bills they’ve championed, like SB729 will keep people in California. The bill signed into law September 29, will take effect in July of 2025.

“This bill is just one small step in providing access to equality in California for LGBTQ families,” said Demissew. They add, “We still have a large array of issues from housing to climate justice to education equality.”

Similarly, some people leave inaccessible cities or anti-LGBTQ ones to attempt a move to Vermont, says Heather Ely. Ely is the executive director for Rainbow Bridge Community Center in the city of Barre, and is also a parent and caregiver. While parenting and taking care of disabled loved ones, Ely is also “dedicated to creating a safer, loving, joyful home away from home.”

Contrarily, there isn’t much housing to move into in the Green Mountain State.

Vermont, while having some of the most progressive LGBTQ laws, has one of the nation’s persistent housing crises, with Black LGBTQ people disproportionate members of the houseless community, according to the Housing Homeless Alliance of Vermont.

Ely expresses that Vermont works for its working people, but more must be done so the LGBTQ community can work, while having affordable housing to return to in addition to food, clothing, and access to health and wellness. Rainbow Bridge works to share information and grants with other organizations to build public access to housing and essential daily resources.

View this post on Instagram

That’s why the Rainbow Bridge Community Center keeps its spaces open without access fees. Unlike housing in Vermont, or the chronic flooding Ely speaks to, the community center “offers a safe place to come and be social with others.”

“Our space is accessible, our space is sensory friendly, and we have a variety of activities, so you can come in and join us and have something to do with your hands, and then organically develop those community ties over time in a way that feels safe and comfortable.”

A part of helping people with housing, says Ely, is building trust and comfortability to seek those resources out in the community.

“I would love to address our housing concerns,” they said. “Those are going to be present regardless [of] who wins the presidential election.”

The last day to vote is November 5. To make a plan to vote before the deadline, visit www.glaad.org/vote.