GLAAD has teamed up with spoken-word entertainment giant Audible to co-curate and produce a three-episode written interview series featuring LGBTQ spoken word artists.

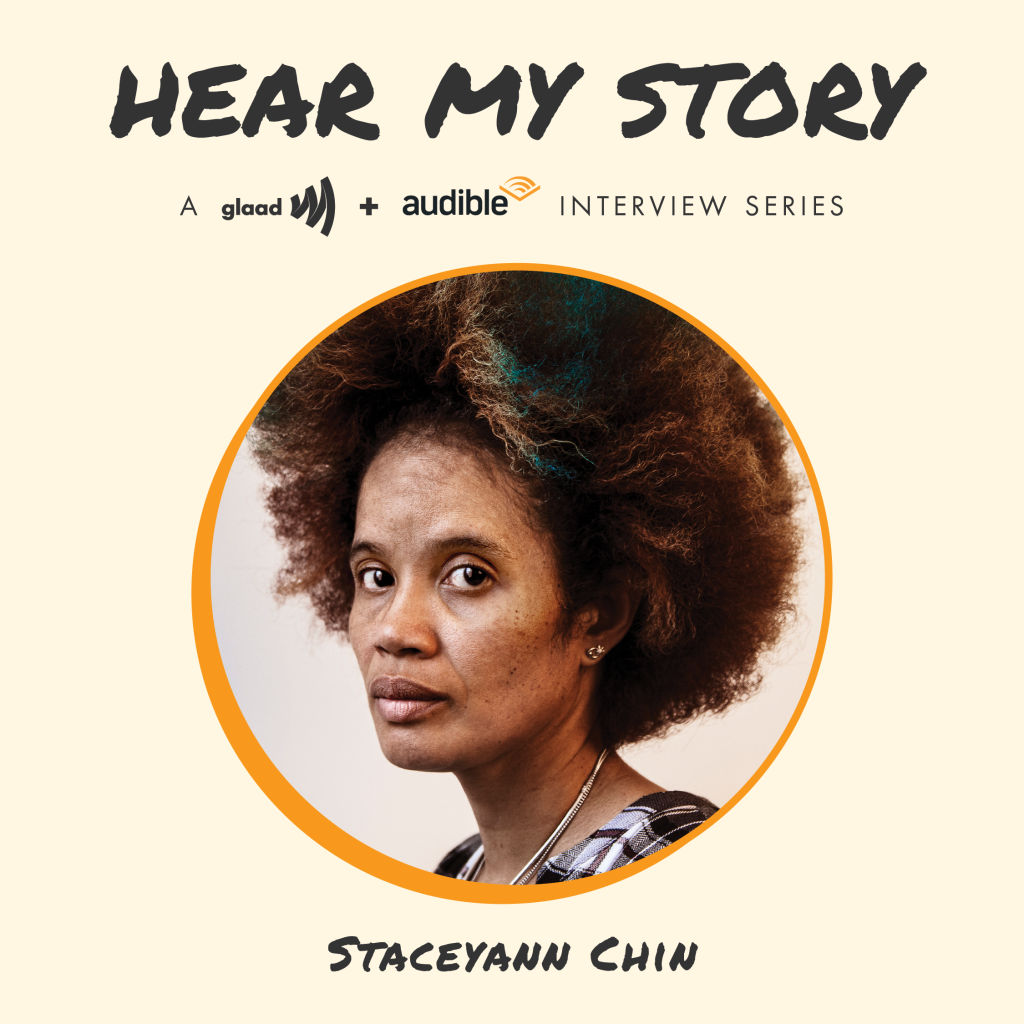

Launching today, the first interview features poet, actor, and performing artist, Staceyann Chin, interviewed by Anthony Ramos, GLAAD’s Head of Talent. Chin is the author of the new poetry collection Crossfire: A Litany For Survival, the critically acclaimed memoir The Other Side of Paradise, and author of the one-woman shows Hands Afire, Unspeakable Things, Border/Clash, and MotherStruck, which is also an Audible Original. She proudly identifies as Caribbean, Black, Asian, lesbian, a woman, and a resident of New York City, as well as a Jamaican national.

Check out the full interview below:

GLAAD: Spoken word art is a strong platform for elevating diverse voices, especially within the LGBTQIA+ community. What do you think it is about this type of content that connects so distinctly across audiences?

Staceyann Chin: think anything that is performed live takes away the additional steps that people need to climb in order to do something. Having the person who created, who experienced, who is telling the story in front of you is very different from having it written down in a book. I think, in a time when we are forced to interact primarily in the digital rather than the physical – we are now more than ever understanding the power of being in the same space, of sharing space. And now that we don’t have that, there’s a way that the human soul is aching to hear people speak in the same room. And the spoken word, whether it be oratorical delivery, whether it be stand-up comedy, whether it be poetry delivered from a stage, whether it be theatre or plays being acted in the same room. There is something that is uncapturable, something that is untouchable, that we cannot do without in our communication as human beings.

G: How does the spoken word performance of your work differ from the written?

SC: There is a thing for which there are no words, for which there is no description! There is a thing that you cannot experience outside of being in the same room. And all of this tied up with the carnal, the flesh, the unmeasurable notion of being human, of being alive.

It does speak to the power of human connection, of a spiritual connection, that goes beyond our ability to define it. It’s chemistry – it’s why one person is attracted to someone but is not attracted to someone else who seems so similar. It’s such a great question of what are we in the flesh.

We don’t have Nina Simone, we don’t have Martin Luther King, we don’t have Prince. So something is lost when they go.

G: For many LGBTQIA+ people, and LGBTQIA+ people of color, inspiration is often drawn from the role models and idols within our community who have changed the way we are seen, heard, and represented in society. Is there someone in the community who has inspired you?

SC: I think I am perpetually inspired and in awe of the black women who continue to create while we hang so low from the bottom of the socio-political ladder. So people like June Jordan, people like Audrey Lorde, people like Pat Parker – I could name you 500 – all of these women who have left work behind for me to use a blueprint for my own journey forward. And then, I find myself being completely bulled over by women in my generation. Women like Whitney Cooper, women like Rachel Cargle, women who continue to redefine how we see our world going forward. Even the young folks who don’t necessarily use the language I’ve learned to use and master over the years – the language of “lesbian,” of archaic notion of gender, all of those things of which we differ – so this young queer community.

What I love about the queer community and the generations that come after is their ability to invent a perspective. In the first wave of the LGBT movement, they were fighting a very rigid idea of sex and gender and sexuality, between things that were considered “normal” versus “not normal.” And so they came out with, “Girls don’t have to look like that,” “Boys don’t have to do that,” “Boys and girls can be who they want to be and date who they want to be and we can definitely date the people who are the same sex as we are.” And then, my generation – Gen X – came along and we said, “Well, not only do we not have to look like this, we can be bisexual. We don’t have to be one or the one way or another. We don’t have to be gay or straight. We can be bisexual. We can be non-gender-conforming. We can be butch. Or just all these ways that we can be.” But then the millennials came along and said, “I don’t even have to be the thing that you say I am. So the sex that you are using and the genders that you are using – that makes no sense to me! So I’m going to do away with that and erase that” and our generation was like, “What do you mean? Our generation fought so hard to be women! What do you mean that you don’t want to be a woman?” That’s the very same thing. Each young, beautiful, radical generation comes along and they reinvent what we think a thing is. They just come and, for lack of a better phrase, just “f*** s*** up” and move everything around and the chess pieces. I mean the game isn’t even chess anymore! And we argue with them because when we fight for something for so long it becomes this institution. We grapple with the notion of the institution, with losing the institution that we built. But perhaps the most beautiful struggle is not so much to fight for any single institution but to fight for the right of any single individual to define or to change the institution as they see fit or as they feel right for them. So I am excited about what this next generation will do. I’m looking at my kid who is a Gen-Z-er and I’m like, “Holy f***!” I can’t even imagine what they’re gonna do.

G: This Pride month & beyond, GLAAD & Audible are committed to centering and lifting up the voices & work of Black LGBTQIA+ people. In your opinion, what content released within the past few years do you think has done an exceptional job at highlighting the experiences of Black LGBTQIA+ people?

SC: This speaks clearly to the point I was making earlier, I don’t think anything is particularly queer or LGBT. What the young queer community is doing is absorbing the heteronormative community. They are saying, “Actually, this is the umbrella and you fall under it.” It’s like a taking over of a culture.

The young singer who did “This is America” – Childish Gambino – the way he came out with the song. The way that he plays around with sexuality. And you look at artists like Chika. My eight year old loves Cardi B and she’s exposed to my work. So hears the word “motherf***er” all the time and she hears about orgasms. And we talk about them where I try to make sense of what she sees or what she understands. But it’s a weird balance. But she likes Cardi B. So when Cardi B comes on, she’s kinda like, “Cardi B is so powerful and she is so strong and she does what she wants.” And sometimes I wanna be like, “NO! I don’t want you to listen to this music about how to have good sex or whatever!” But at the same time, there’s a part of me that feels like it’s good for her to see a strong, unapologetic, uncensored black woman in pop culture. You shouldn’t just see me who’s kind of on the fringe of that mainstream culture talk about owning my body and having power over my body.

The answer that I have for you is Lizzo. The way that Lizzo owns her body, the way that Lizzo is talented with her words, the way that Lizzo decides that she is enough as she is and that she is not too much as she is. It’s astounding and it says so much for women’s rights. It is the counter-narrative to me, seeing a duty to embracing superbly binary in our interpretation of gender. It’s like the straight community and the mainstream community has gone apes*** on what femininity is now. So you can get botox every day and craft yourself and buy a butt. There’s an understanding of a much preferred norm or a much preferred valuable norm that everyone is slowly moving towards or being ushered towards. And then Lizzo is a bit of a counter-narrative. Sometimes it feels like Lizzo is the balance that black women need. Again, the perfection that Beyoncé exists in.

When I was young, we had expected things to be where lots of things to fight. We had the Ellens and we had all of these notions of queer culture and we had our icons who were queer, the RuPauls, there was a way that we understood that we were different and that we had this own sector of society and we had our own icons. Young people who are now moving through the world don’t necessarily believe in the notion of this static sexuality. I don’t think we have lesbian icons – the closest thing I can think of is Lena Waithe. Even her, it’s not like, “OMG, there’s this great lesbian showrunner or this great lesbian producer or this great lesbian mogul.” You know, Lena Waithe is this great person who happens to exist right now within the context of this sexuality continuum. This is where she is right now. And we understand that it could shift in any way, at any point, because the generation that has come before and this generation now continues to push for people to have the right to live anywhere on that continuum as they choose at any moment that they choose.

I think the LGBT community is moving away from creating its own empire and now we’re just taking space in the empire that already exists.

G: Thanks to services like Audible, access to LGBTQIA+ stories & content is now easier than ever. What kind of LGBTQIA+ story still needs to be told / heard?

SC: I would like to see more stories that have more nuance. I’ve watched Queen Sugar, I’ve watched The L Word: Generation Q. They still feel like they are responding to people’s ideas of stereotypes of us. I think we have moved dramatically towards it already but I think we still need to move towards like the immigrant lesbian story, the immigrant transgender story, that isn’t about her being (worried about being) killed in her native country so she flees here so she can be respected as a trans woman. You have trans people who are ordinary people who exist in the city and are trying to keep their jobs and date people without it being this spectacular event. Kind of like the LGBT “Friends.” You have somebody who’s not that cute, somebody who’s not that bright, somebody who’s not that successful – and they’re all friends and they’re figuring out rent in the city which all of us in the modern world understands and is navigating.

So I feel as if we need more ordinary stories that reflect ordinary people, ordinary queer people – people who aren’t in distress or at death’s door or needing to be saved by the audience member where you watch this thing and all you want to do is donate to someone else. And I think also, we need to have stories that depicts relationships – solid beautiful amazing relationships between people in the LGBTQ community and people who are not. Like those familial relationships and friendships, not necessarily sexual. And the thing that we haven’t really done in any kind of major way is my own story of raising my kid against a heteronormative, nuclear notion of family. All the families we talk about are these gay couples who adopt a baby and there are so many ways that gay people are parenting now. You have the blended families who are navigating new families with heterosexual couples and grandmothers and friendships with kids and getting into good schools. And not like the funny, “Modern Family” where we’re all stereotypes.

And like real stories and like all of my friends could have their own sitcom just now. Like even my own story as a single woman deciding I’m going to have a kid. Being a single black lesbian. Being a single black lesbian who’s an artist. Being a single black lesbian who’s an artist who doesn’t have insurance. And how ridiculous it is that I’m running across the globe hunting sperm when I’ve spent the last two decades avoiding it at all costs. That is pretty much the norm now for people who are 30-40 now. How is it that I have a family? How do I have money? All of these stories of LGBT people who are just going ahead and doing it.

Not every gay male couple can just get up and pay for surrogates. Surrogacy is not just a bottle of coke and spring water; it’s very, very expensive. You have to pay for the life of another human being for a whole year. You have to pay them and all of their health insurance bills and all of their medical costs. And then you have to do this while you are unsure of if it’s going to turn out the way you want it to.

G: How does the general response to The Other Side of Paradise continue to impact your work? Did any responses surprise you, and if so, in what way?

SC: That was the first kind of work that I did that was validated deeply by people who didn’t necessarily see me on stage. Like people who read that book have spread that book far greater than my voice could go, which is in Uganda and townships in South Africa. There were so many different kinds of people who read that book. There were old women in Columbus, Georgia, who were ninety years old and heard me read from that book and found commonality with it.

One of the things that I wanted to do with The Other Side of Paradise was to make sure I wrote a book that didn’t play out the stereotype of being, “Oh, I’m a lesbian and I’m really struggling in Jamaica and I come here and I have a happy lesbian life.” I wanted my own story to be more than my own queerness because that is the shortfall of LGBT pop culture and media gatekeepers. What they do with people of color, particularly with black people, is that they reduce us to one part of who we are. I’m not just a lesbian. I’m a granddaughter and I’m half Chinese. I majored in biophysics and math in my first degree and I studied literature in my second degree. There are so many other things that are interesting about me. Sometimes, it’s like it’s only my lesbian identity, especially when they sensationalize my lesbian identity, that leaves very little room for the nuances that help to paint a true picture of who I am and perhaps a relatable picture of who I am.

If I am only the girl who is running away in the dead of night because I’m being violently and homophobically attacked in Jamaica, there is very little of my humanity that is available for people to consume in the story. But if I was a little girl who was left by my mom and I was a little chatty and precocious, and I worked hard in school. And if I had a crush on my friend but I didn’t know it was a crush. And if I had a desire to have a kid when I grow up. Those are the parts of you that allow you to be completely human to the people who don’t necessarily experience the brutal trauma and tragedies that are associated with living in societies where violence is a way that people navigate your queerness.

G: Can you tell us a little bit about your audio production of Motherstruck!? and your experience taking it from the stage to the ear?

SC: There is an audio version of it {on Audible} and we’ve also filmed a little bit of a pilot. A couple of other people are still interested in what we are going to do with that. I think it’s going to be a series. It’s gonna be pretty cool.

Where we can do more than just present this picture of this fleeing lesbian in my twenties finding my footing here. There’s just so much to this story. Like I’m standing here in a playground with my kid, she’s roller skating around the park, and I’m trying to keep my eye on her while I’m doing this interview.

Every mom in the world knows that: I’ve got this thing to do, and I’m doing it! It’s fun that it’s about queer life and queer culture. Look at me now: half of my attention is trying to tell you the story and the other half is watching my kid zoom by and thinking, “Jesus Christ, I think she’s going to fall!” And that’s life! It’s so much more full of a picture than what they reduce us to, you know?

G: And Crossfire releases in audio this month as well. What are you most looking forward to about that release?

SC: It’s poetry from the last twenty years of my work that is now catalogued in a book called Crossfire, a litany for survival. It’s got sex poems from when I was young and having a lot of sex. I’m not having any sex now because I’m now a mom in a city with very little opportunities for a single mom to facilitate having any kind of intimacy with a stranger. And COVID exasperated that alongside the general lockdown.