Join GLAAD and take action for acceptance.

Trending

- GLAAD’s Black Queer Creative Summit Returns to Los Angeles for a Powerful Second Year

- The GLAAD Wrap: ‘Kiss of the Spider Woman’ ‘After the Hunt’ and ‘Fairyland’ in theaters, trailers for ‘I Love LA’ ‘All’s Fair,’ and more!

- RECAP: Supreme Court to Rule on Protections Against Discredited and Unsafe Conversion “Therapy” Practices on LGBTQ Youth

- We All Could Use Some Queer Joy! Be a Part of The Skin Deep + GLAAD’s New Collab

- Facts and Action for Banned Books Week

- Write It Out! Launches Annual Campaign to Uplift People Living with HIV Through Playwriting

- GLAAD Gaming Announces New Queer Emerging Developers Program

- Finding Yourself Begins With Celebrating Others’ Differences

GLAAD is spotlighting LGBTQ-inclusive books and authors who are expanding understanding and accelerating acceptance of LGBTQ people.

Books about and by LGBTQ people, as well as books about race and racism, are the most challenged and banned in the U.S. GLAAD celebrates these stories and writers. Here you can read some of their work.

Teach Like an Ally: An Educator’s Guide to Nurturing LGBTQ+ Students

In Teach Like an Ally: An Educator’s Guide to Nurturing LGBTQ+ Students, veteran classroom teacher and celebrated transgender advocate Flint Del Sol weaves humor, storytelling, and expertise into a hands-on guide for educator-allies. Del Sol offers actionable strategies that you can implement in classrooms right away. Building a positive school climate doesn’t have to be intimidating, In Teach Like an Ally, you’ll learn how educators can support each other and how we can all give LGBTQ+ students the best possible chance to flourish.

A Letter to the Mother Who Called Me a Groomer

I am, from the deepest recesses of my heart, so truly sorry.

I am, from the deepest recesses of my heart, so truly sorry.

Not for who I am or who your child is, but for the feelings of loneliness, confusion, and resentment that have made a home in your life. Because honestly, I can’t imagine a job harder than being a parent. Teaching is challenging, but when that last bell rings, I say goodbye to my students and go home to a differ- ent life. At the end of the year, I pass them along to a new set of teachers and cross my fingers hoping that they will carry something from my class along with them. But really, there’s no way to know for sure. My investment, I hope, is a meaningful one, but it is still brief.

But you – you once held your child in your arms before they could speak and imagined a life for them. You manifested a world that was kind and secure and loving, and you played out how they would live in that world. You picked a name, you painted a room, you chose baby clothes, and you watched them night after night just to be sure they were breathing. You taught them to roll over and crawl and stand and walk. When they started school, you read to them every night and helped them trace the letters of their name. You watched them grow out of their shoes too quickly, you introduced them to the music you like, you picked them up early from sleepovers when they got homesick. There was a time when you knew your child better than any other single person in the world, including them.

I can’t even begin to imagine how disorienting it must be, no matter how much we all know it’s coming, to watch that child grow into a person. Puberty comes lightning fast and, with it, an avalanche of brain development. Neural pathways are forged, along with a host of new connections between neurons, and suddenly, that brain is in the body of a whole teenager, not a child. I know it happens to all of them, because I’ve been teaching high school for my entire adult life. Suddenly, the kid who once was struggling with a rolling backpack twice his size is 6 feet tall and raising his hand in the middle of class to ask “if time really exists.” Students who have obediently followed their parents to Sun- day church service every week since they could walk are now dodging their moms’ texts, chatting at lunch, and chatting together about the paradox of omnipotence. And a star athlete who is less than a year away from a full-ride scholarship to his father’s dream school is pacing in the hallway after school, rehearsing how to tell him that he doesn’t want to play football anymore.

As terrifying as it is, that change in them isn’t against nature – it is nature. It is not only normal, but developmentally necessary, for children to forge their own identities.

And maybe you knew that. It’s possible that you saw this moment coming, but you thought it would be different. You hoped that your child’s departure from your worldview would manifest as something more manageable. Some- thing, anything, but this. You thought you raised them differently. In fact, you swear you did. You can’t believe for a single moment that this kind of change came out of nowhere, or that the child you held in your arms was actually some- one else all along. This has to be something forced on them, something they didn’t choose. They were tricked. They were influenced. This isn’t them.

And I know believing that is easier. Because the alternative is that you missed something. If what we say is true – that we were born this way – then a piece of your child has been invisible to you for their whole life. It was there in your arms, it was there when you watched them sleep, it was there when you read to them – it was there right from the start, and you didn’t see it.

And sitting in that is painful.

Here, there is a grief that can’t be ignored.

But instead of facing it, it is simpler to push that grief down and replace it with rage. There’s nowhere to direct grief, there is nothing to do but hold it. But rage – rage is a weapon. It’s a weapon begging to be used. That’s when you found me.

And so, as I said before, I am sorry. I am sorry that I can’t absorb your grief. I am sorry also that taking on your rage won’t help you either. The truth is that no parent has ever strengthened their relationship with their child by hurting someone else. There is no one to yell at, no complaint to file, no school board meeting to attend, no bill to pass, no president to elect, that will change who your child is and always was. Seeing me might have helped them envision a path away from shame, but there’s nothing I could have done, just as there’s nothing you could have done, to change the essential truth of their identity.

You might be able to convince your child to hide again, to retreat into them- selves, to push down the knowing that burns under their skin, but you can’t reshape their heart. You can’t mold the person you want out of the person who is.

And, truly, wouldn’t loving them be easier?

Because it’s not too late. You could start right now. There is still time to turn this ship around and rebuild trust with the person you once promised to love unconditionally. You might think it’s your love that’s guiding you in this moment, but that’s not what this is. Fear, rejection, anger, resentment, disgust – these are feelings that don’t have a home within love.

I won’t anticipate that you will ever see me differently, but I will hold on to the hope that one day, not too long from now, you come back to the child who needs you.

Purchase Flint Del Sol’s book here.

With Valor and Visibility: The Next Chapter of Transgender Military Service

Transgender people have been serving openly, capably, and honorably in the U.S. military for years. Their contributions have made our military and country stronger and safer.

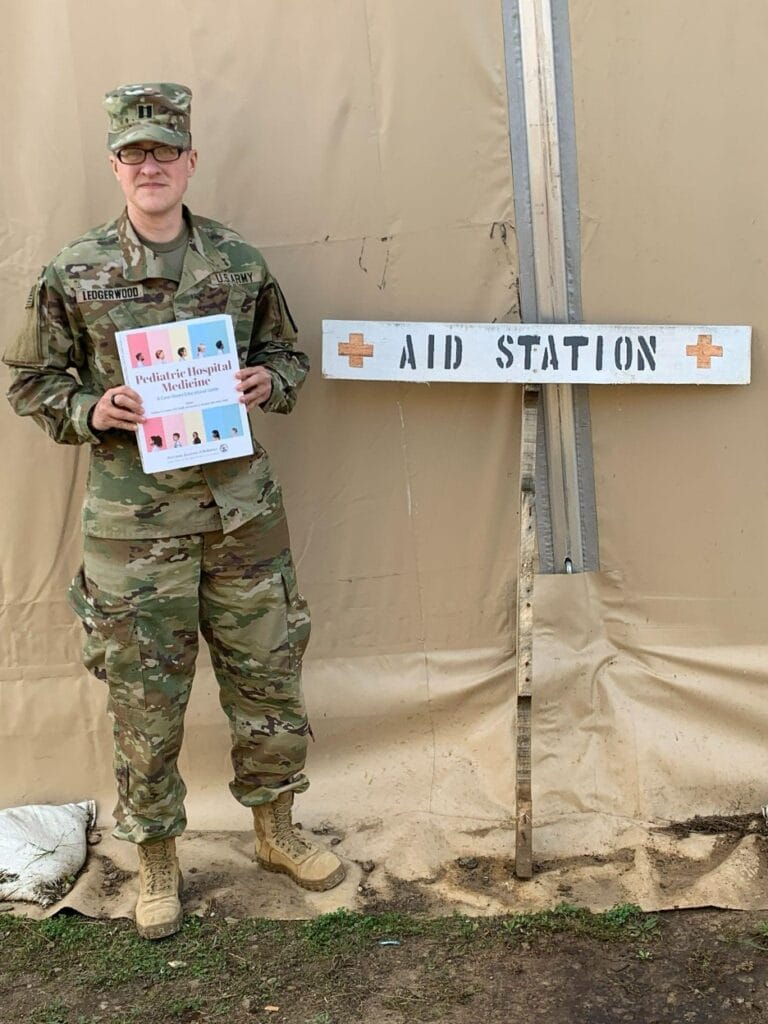

With Valor and Visibility: The Next Chapter of Transgender Military Service features 47 stories of trans service members in their own words, including caregivers like Major Dr. Riordan Ledgerwood and Staff Sgt. Zane Alvarez of the U.S. Army, and aviator, Capt. Mara Jett of the U.S. Air Force.

Here are excerpts that capture their courage, resilience, and unwavering dedication even while serving under the shadow of uncertainty.

Riordan Ledgerwood, Major (Doctor), U.S. Army, 2014-Present

I fought not to cry that night, but I failed.

On the night of April 12th, 2019, I was working as a new doctor in Walter Reed’s Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). I was in my first year of Pediatric Residency, learning how to become a military pediatrician. Oh, and I happened to be trans.

I had worked my entire life to achieve my goal of becoming a physician. When I heard about the incoming military trans ban, I felt I was put into an impossible situation.

I had to choose between my dream of being a doctor and being true to myself. I was regularly working 80 hour weeks and barely had time to think. I felt defeated. There was no right answer. As the date of the ban loomed ever closer, I was forced to choose. After a prolonged struggle, I came to my Decision.

I chose my career.

It was this which caused me to be working in the Walter Reed NICU at midnight, fighting back tears as the ban came into effect. The senior resident next to me didn’t know how to help me, what to do. No one did. So I walked away to the privacy of a bathroom stall and finally let myself cry.

The next 655 days brought me down to a level of misery I truly wish for no one to ever experience. Every day felt like a fight, to wake up, plaster a smile on, and do my best. And despite it all, my best was good enough.

I did well in my pediatric residency, but I did it as only the shell of a person. I experienced daily misgendering and worried that one wrong move would get me removed from my program. I refused to let myself be closeted, so I tread a very fine line in my efforts to be seen as I was, as who I was.

I worked hard. I excelled and I fought for recognition. I was a person who wasn’t allowed to exist, a person who worked daily inside the walls of the President’s hospital. I took the journey day by day, and step by step, and soon enough I finished my residency. I graduated towards the top of my class and earned the honor of Pediatric Resident of the Year before graduation in 2021.

2021 was an incredible year of change for me. It was my transition from training doctor to an independent physician, but of course that wasn’t the only transition. The moment the trans ban was lifted in Jan 2021, I sought care to finally become more than a shell, more than a zombie in cranberry scrubs.

In the three years since, the changes have been incredible. And I’m not talking about the facial hair or new muscles, or even my wonderfully deep and rich voice. I’m not even talking about how I hardly get misgendered anymore, though that has been such a gift. I’m not talking about becoming a mentor to medical students and residents, to medics and young enlisted soldiers, though seeing them succeed has meant the world to me.

It’s the weight. Or lack thereof.

An incredible weight has been lifted off my shoulders. I smile more. I laugh more. My patients and their families get to experience me as my whole self. I can finally care for my patients as my whole self. I am a better doctor. I am more patient. I am more caring. I am more understanding.

I am better, because I am who I was always meant to be.

A physician, an officer, who happens to be trans, and is finally, completely themself.

Mara “Casper” Jett, Captain, U.S. Air Force, 2020 – Present

So there I was, having just arrived at Pensacola Naval Air Station as one of the newest and dumbest 2nd Lieutenants in the Air Force. My very first duty station. I was so excited to start my career as Combat Systems Officer (CSO) and had arrived to begin Undergraduate Combat Systems Training (UCT) in February 2020. COVID-19 threw a wrench into everything mere days after I reported. Suddenly, my training wasn’t starting in a few weeks, it was starting in six to nine months. Six to nine months in a new city, a new base, and knowing nobody.

For years, starting from when I was six, I had struggled with my gender. For a long time I had no context for these feelings, of wanting to be a girl so bad it hurt, feelings I could never voice. I gained some context to my hurt when I was twelve and I heard the word transgender over the car radio as my parents listened to a talk show host spouting hate and bigotry. That one glimpse into the wider world gave me two almost simultaneous realizations. Firstly, this transgender thing might apply to me! Secondly, if it does, everyone I have ever known would hate me. So I repressed, I hid from myself, ran from my feelings, did my darndest to be the perfect son my parents wanted me to be. Using school, and as many activities I could shovel onto my plate, to box up and bury my feelings.

The trouble with running from your feelings, is that they eventually catch up to you. I couldn’t hide from myself anymore. My distractions and escapes were limited. Alone in the UCT student housing I struggled. It took me months of wrestling with myself, of reading up online, of studying the bible, reconciling my beliefs and my identity, but I eventually figured myself out. I was a woman and there wasn’t a damn thing I could do about it.

In September 2020, when I finally accepted myself, the second ban on transgender service members was still in effect. So, I told myself, “This is fine, just wait it out,” and that’s what I did. I started UCT and began training and most importantly flying. Staying closeted, I waited. In January 2021 the ban was lifted again, but with little to no guidance, especially for flyers. So rather than coming out then and getting pulled from flight status in the middle of the training pipeline I opted to wait. Guidance eventually came out, but gender dysphoria remained a grounding condition. I figured I had already waited this long, might as well wait until I finish my training before taking those steps. I came out to my family and some of my friends that weren’t part of my Air Force life and waited.

As I finished UCT training, I earned a Weapon Systems Officer slot on the B-52, or BUFF, the world’s premier nuclear bomber. To Barksdale AFB I went to continue my training. While at the Formal Training Unit (FTU) there, I first told the Air Force I was transgender. A small footnote on my Personnel Reliability Program (PRP) paperwork, a program “to ensure the highest possible standards of individual reliability in personnel performing specialized duties with certain types of weapons,” got me a phone call about being transgender. But hey, my paperwork was approved, I got to work with nukes.

After the FTU, I was stationed with my Ops squadron at Minot AFB. It took several months to get fully qualified on both the nuclear and conventional sides of our mission. The day after getting qualified, I scheduled a meeting with my commander. I had reached the end of the training pipeline, where I had promised myself to come out and pursue my transition. My meeting went well, my command team already knew from my PRP paperwork and they supported me.

Things went well but slowly and I never really came out to my unit at large. I wasn’t subtle, but in a glass closet you might say. I changed my name on our daily brief while I was presenting. Two weeks later my squadron members handed me a new name tag with my chosen name on it. As my transition progressed and I got my transition plan and hormones I got taken down off of flight status. The next several months were very busy for my squadron; training for the nuclear mission, attending the Red Flag exercise, and putting together Bomber Task Forces. I did my best to support them from the ground, got myself a callsign (buy me an unleaded drink to learn that story), and threw as much weight as a junior captain could to get back on flying status. It took nine months, but as of this writing I have been back on flying status for a month. I am preparing to generate missions and support my country, the Air Force, and my squadron, all of whom have accepted me as I am.

I am a woman, I am an aviator, I am me, and no one can take that away.

Zaneford Alvarez, Staff Sergeant, U.S. Army, 2013-2025 and Technical Sergeant, U.S. Air Force Reserve 2025- Present

I am incredibly grateful for the results of my transition. My mother commented, “You grow a better beard and more chest hair than your father!” I still laugh at the thought of this. My confidence now precedes me everywhere I go. To those who doubted my willingness to volunteer for deployment, I would honestly scoff and even laugh. I come from a long line of service under my family name, Alvarez. My grandfather, Colonel Jose Alvarez. My father,

Sergeant Major Carlos Alvarez. All my uncles and aunts from my paternal side of the family, serving in the Army and Air Force, covering different fields, including combat arms, combat engineering, aviation, support, and intelligence.

Then there is me, Staff Sergeant Zaneford Alvarez in the Medical Corps. I so longed for any opportunity to do my job in a deployed setting that I volunteered for every mission that came my way.

One mission that stands out was being sent to Kosovo under emergency circumstances due to the tragic death of a soldier. It was a solemn and challenging moment, especially since I had little preparation for it. Normally, we receive Traumatic Event Management training before such an event, but I hadn’t had the chance to attend before this mission. I was assigned to work with a doctor and a chaplain I had never met before our arrival in country.

At the time, I was just over a year on hormones, with a deeper voice and facial hair, clearly not resembling a girl anymore. Before we started, I felt it was important to inform the doctor, CPT Bryant, about my situation and ask how she preferred to approach it. She looked at me up and down, paused, and said, “Be yourself. If someone gives you a problem, send them my way.” Her response took me by surprise, but I was filled with a sense of relief and validation. For the first time on a mission, I was seen and accepted for who I truly am. It allowed me to fully focus on providing the necessary care I was trained to deliver, without the burden of hiding or explaining my identity. This experience remains to be one of the most cherished memories in my career: knowing I could be myself and still fulfill my duties with the support of my team. I would do it again in a heartbeat, not just because of the mission but because of the affirmation I received during that critical time.

I can confidently say that being open about my identity has never hindered my ability to perform my duties or lead effectively. In fact, it has provided a unique platform for me to educate others and offer perspectives that many might not be familiar with. Being transgender has deepened my empathy and made me more of a compassionate leader, particularly when it comes to understanding the diverse experiences of my soldiers. For instance, I’ve had female soldiers express frustration that some of their male counterparts don’t fully grasp what it’s like to navigate the military as a woman. My own experiences helped me relate to these concerns and advocate for a more inclusive environment. In other situations, sharing my story has empowered others to support their loved ones who are beginning their own journeys of transition.

I’ll never forget a soldier who told me, “My niece, I mean, nephew just came out to me, and I told him it was going to be okay, and I still love him no matter what.” They reached out to me for advice because they knew I could relate and provide the guidance they needed. Every one of us has our own unique journey, but the one thing that unites us is the oath we took when we raised our right hands and pledged to support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, both foreign and domestic. This bond, shared by all service members, is something I hold in the highest regard, especially among those who are transgender. It’s a testament to our shared commitment and resilience, no matter our individual stories.

Regarding drug tests, showers, and bathrooms, most people are so caught up in their own lives that I often go unnoticed. These aspects of military life, which many assume would be problematic, have never been an issue for me. Frankly, others tend to make a bigger deal out of it than necessary. The real challenge for me was getting my cardiovascular endurance up to par. But after putting in the hard work, I’m now the one pacing the soldiers and pushing them to run fast. It’s a reminder that with enough determination, what others perceive as obstacles can be opportunities to lead by example.

American Teenager: How Trans Kids Are Surviving Hate and Finding Joy in a Turbulent Era

Nico Lang (they/them) is a nonbinary award-winning journalist with over a decade of experience covering the transgender community’s fight for equality. Their work has appeared in major publications, including Rolling Stone, Esquire, the New York Times, Vox, the Wall Street Journal, Salon, Harper’s Bazaar, Time, The Washington Post, and the L.A. Times. Lang is the creator of Queer News Daily and previously served as the deputy editor for Out magazine, the news editor for Them, the LGBTQ+ correspondent for VICE, and the editor and cofounder of the literary journal In Our Words. Their industry-leading contributions to queer media have resulted in a GLAAD Media Award and 10 awards from the National Association of LGBTQ Journalists (NLGJA). Lang is also the first-ever recipient of the Visibility Award from the Transgender Legal Defense and Education Fund (TLDEF), an honor created to recognize their impactful contributions to reporting on the lives of LGBTQ+ people.

Media coverage tends to sensationalize the fight over how trans kids should be allowed to live, but what is incredibly rare are the voices of the people at the heart of this debate: transgender and gender nonconforming kids themselves.

For their groundbreaking new book, journalist Nico Lang spent a year traveling the country to document the lives of transgender, nonbinary, and genderfluid teens and their families. Drawing on hundreds of hours of on-the-ground interviews with them and the people in their communities, American Teenager paints a vivid portrait of what it’s actually like to grow up trans today.

From the tip of Florida’s conservative panhandle to vibrant queer communities in California, and from Texas churches to mosques in Illinois, American Teenager gives readers a window into the lives of Wyatt, Rhydian, Mykah, Clint, Ruby, Augie, Jack, and Kylie, eight teens who, despite what some lawmakers might want us to believe, are truly just kids looking for a brighter future.

KYLIE

TORRANCE, CALIFORNIA

JUNE 2023

1. ALL-AMERICAN GIRL

Kylie Yamamoto smooths her orange bangs in the muted reflection of her iPhone screen as she prepares to look her very best for the commencement of the Los Angeles Pride Parade. Kylie is right at the front,just behind the parade’s grand marshal, the comedian Margaret Cho,who sits atop a convertible painted in rainbow stripes that fan out like overlapping sunbeams. Cho, holding a chihuahua in her left hand and a parasol in her right, is the object of much attention among marches with PFLAG, the national support group for LGBTQIA+ people and their families. The most excited member of the contingent is a peppy person in a rainbow NASA t-shirt loudly advertising the actress’s resume like an overzealous talent agent. “There’s Margaret Cho!” they say, approaching one bystander after another to bring them the good news. “I used to havetheAll-American Girl box set!”

Kylie is accompanied at the head of the parade by her equally lively mother, Janet, who pushes her to partake in the excitement by showing the guest of honor her sign: “I’m CuTie,” with its conspicuously capital-ized “T” decorated in the colors of the Transgender Pride Flag. Jane has her own corresponding posterboard reading “I Heart My CuTie,”a message she felt was more subtle than the comparatively obvious alternative of “I Love My Transgender Daughter.” “If you see it, you get it,” Janet remarks, adding with a smirk: “And if you don’t, I don’t care.” Margaret Cho does appear to get it, flashing a flit of a smile before resuming conversation with a bearded chaperone in Daisy Dukes and a dangly beaded top resembling a chandelier.

The signs are famed staples of Yamamoto prides, although they have evolved slightly over the years. When Kylie was much younger and her parents weren’t sure whether she was a gay boy who liked to wear sparkly dresses or if there was something more to it, the “T” was designed in the colors of the standard Pride flag—that way, Kylie would be represented no matter where she ended up on the LGBTQIA+ spectrum.

Today, Janet has also brought everyone silken leis woven together from ribbon; hers is glossy rainbow, while Kylie sports a pink-and-blue necklace over her newly acquired PFLAG t-shirt. Although Janet chooses not to change into the tee, preferring instead to wear the flowing red vel-vet poncho she came in, Kylie almost didn’t get a shirt at all. A volunteer organizer informed Janet shortly after we arrived that marchers had been expected to line up at 9:00 a.m.—almost two hours ago—if they hoped to secure one in their size. Luckily, a woman who sympathized with their plight gave Kylie a leftover large from her contraband stash, over which Kylie immediately draped an unzipped black hooded sweatshirt.

Janet is a longtime member of the San Gabriel Valley chapter ofPFLAG, one of the only branches with its own space for Asian-American and Pacific Islander families. She is also a dedicated advocate for trans-gender rights: Janet has spoken at numerous conferences across the country, appeared in educational films with her daughter, and visited the White House last year to represent affirming families of transgender children.

But as Kylie will tell me later, she felt out of place among kids whose lives had been irrevocably altered by legislative attacks on their rights and health care, feeling as if she had nothing meaningful to contribute to the conversation. After all, she lives in one of America’s most progressive and LGBTQIA+ friendly states: California, which last year became the first in the United States to declare itself a sanctuary for transgenderpeople seeking gender-affirming medical treatments.1It felt so strange, standing next to children who could feasibly be forced to travel to her state for their health care needs and realize that, aside from some minor quibbles, her life is actually pretty fantastic. “I’m always put in the situation where I’m the person from Cali-forn-yuhh,” she says, practically belching her home state’s final syllable. “I’m listening to them talk about their issues and I’m like, “Things are great. I’m in a supportive city. I have good friends. I don’t have laws being made to limit my life.”

Kyle almost didn’t come today, attempting to back out just as her mother beckoned her to get in the van. She had preferred to stay in her room and play the first-person shooter game Overwatch with her circle of closest confidants, whose specific form of virtual bonding is dying together over and over again. Like many seventeen-year-old girls, Kylie just wants to be where her friends are, checking out creamy boys at the beach and gossiping about their school’s continuous realignment of interpersonal constellations: which friends are fighting, who is cheating on whom. She had expressed her displeasure at being forced to attend Pride by giving Janet her famous silent treatment, barely speaking during their hour-long car trip from Torrance, the South Bay enclave their family calls home.

Kylie doesn’t know where she fits in with her mother’s crowd, always with their clipboards, visors, and travel-sized sunscreen at the ready. Around Kylie is so much energy and excitement that she doesn’t quite share from the Disney Pride in Concert gays doing side-to-side stretches as the Psychadelic Furs’ new romantic anthem “Love My Way” plays from distant speakers to the mob of brides flanking a wedding-cake car. In a scrumptious morsel of irony, our groups have been positioned crosswise from the Hollywood location of Chick-fil-A, which is surprisingly busy this morning.

The parade itself goes by with a pop and flash, the bang of adrenaline compressing time with such force that the event feels over before it begins. Kylie, despite her earlier misgivings, warms up to the festivities as soon as she turns the corner of Hollywood and Highland, her face shining as she is greeted by a crush of body glitter and unconditional love from every direction. The sweet summer smell of bacon-wrapped bratwurst wafts from sidewalk grills as onlookers whoop and clap in their rainbow butterfly wings, sailor hats with matching white bibs, and scanty undergarments passed off as outerwear. Other spectators prefer message t-shirts, whether earnestly declaring that they are the “Proud Aunt of a Gay Nephew” or broadcasting their attraction to gentlemen of mature vintage: “I Heart Hot Dads.”

After Kylie shares a sheepish wave with a queer woman wearing an“It Wasn’t a Phase” tank top, an old friend spies her mother from the crowd and runs up to give them both a hug. “Hi, cuties! I love you!”she yells in reference to the sign that Kylie no longer knows what to do with, its novelty having worn off after the first few hoists. Janet doesn’t make it through the entire route, her pulsing feet ready to burst, and she finds a nearby bench to rest, bequeathing to me her posterboard for the remainder of the march.

Kylie is so energized by the PFLAG group’s reception that she wants to keep having fun even after the parade is over. As Janet enjoys a reprieve from her blisters, we walk past the muted counterprotest—a man in a red cap listlessly standing next to an “Ask Me Why You Deserve Hell”placard—to watch synchronized line dancers in chaps and fringe jackets hoedown to a medley of pop hits. First comes the cupid shuffle to JuiceNewton’s cover of the country-pop standard “Queen of Hearts,” followed by an obligatory routine set to Kylie Minogue’s “Padam Padam,” already the gay anthem of the nascent summer, which the emcee explains the group threw together last night. The best performers are the ones who put extra flourish into it; a dancer with jean shorts ripped far up the sides is always adding an extra swish, kick, high knee, or clap to the choreography.

Seeing how much this day means to everyone and how much Kylie’sgroup meant to the crowd—who kept cheering and shouting thank you to PFLAG parents for supporting their queer children—has been yet another reminder of how blessed Kylie is. “It made me really happy when I saw how many people were supporting us and cheering for us,” the girl tells me as the troupe dances to “Boys and Girls,” the Britpop act Blur’s paean to sexual fluidity. “I feel more conscious within my decisions and my life. I feel like I almost gained consciousness during COVID, not in the literal way. I became aware of my actions and how everything affects me. I think I woke up.”

Kylie has led a rarefied existence, and if her mother sometimes accuses her of being coddled, too comfortable with the charms of her life, the allegation is something of a backhanded compliment to Janet’s own parenting. Kylie has never wanted for anything, whether the latest iPhone model or the love of her parents, who were her most vocal supporters even before she had the words to express who she was. When Kylie was seven, Janet took her to the mall after her daughter told her that she no longer wanted to wear boys’ clothes, and they spent three hours trying on anything Kylie wanted: flowy dresses, dangly bracelets, and virtually everything else they saw. With the help of a sympathetic retail assistant at a tween clothing store, they left with fourteen outfits, treating Kylie’s father, Dave, to a fashion show when they got home. Kylie began taking puberty suppressors at thirteen in consultation with doctors and psychologists and got her birth certificate corrected shortly after at a courthouse near their local mall.

The Yamamotos were the very last people in the courtroom to be called that day, and when the judge asked Kylie to state her deadname one final time for the court record, he added with a laugh, “Well I bet you don’t want to say that anymore. Why don’t we make that happen then?” After she was legally recognized as the girl that she had always been, their family members each took turns taking photos with the judge, who gave them a tour of his office to celebrate the milestone. Further adding to the spirit of triumph, Kylie cartwheeled all the way to the exit elevator like an overeager pageant contestant, except that she had already won the whole thing.

In my time spent with the Yamamotos, watching game show reruns and eating Dave’s delicious fried fish, Kylie will tell me that she doesn’t“have any problems,” and that coy admission isn’t entirely off base. On one of our daily walks to a playground in her neighborhood, she recalls that the only time she’s ever been bullied for her gender was when another student shouted, “Kylie is a trans girl!” in the middle school locker room. Her peers responded with bored shrugs, not understanding what the fuss was about. Now in her senior year at Torrance High School,Kylie says that being transgender is a non-issue, joking that her class-mates are too busy thinking about themselves to worry about her. “My whole friend group is gay,” she says. “The majority is still straight and cis, but I feel like it’s about fifty-fifty. Our school is really, really diverse.”

Torrance High’s Gender-Sexuality Alliance (GSA), she adds, is among the school’s largest student groups, at around two hundred members.That’s a tenth of the entire student population; the club is so big that it’s forced to break into smaller groups to accommodate everyone who wants to attend its weekly meetings. When the full group gathers—whichcan only happen once a month for logistical reasons—they have to use the gymnasium. Kylie timidly admits, however, that she doesn’t usually show up to GSA because the meetings have a habit of conflicting with her commitments for Botany Club, in which she serves as vice president, andJapanese Club. While she loves her queer friends, Kylie says they can’t compete with Mother Nature: “A lot of people ask me, ‘Why are you in that club?’ and I’m like, ‘Girl, I love plants. I love gardening!’”

But if Kylie is living a teenage dream of her parents’ tenacious creation,the fortress built to keep her safe feels newly vulnerable, cracks splin-tering across its surface as June’s infamous gloom settles over greaterLA like drying concrete. Just five days before she marched at the front of the Pride parade, violence had erupted outside the school board of the Glendale Unified School District, which had voted that same day in favor of a resolution recognizing Pride month.

Despite LA’s reputation as a bulwark against intolerance, a liberal bubble within one of America’s most progressive states, this wasn’t even Southern California’s first such incident within the past year. Just days before the beginning of June, a transgender teacher’s Pride flag was burned outside of Saticoy Elementary School in North Hollywood after conservative parents protested The Great Big Book of Families – a book recognizing that some children are raised in same-sex households – being read aloud during a school assembly. In April, the Chino Unified Valley School District (CVUSD) voted 4-1 to adopt a resolution requiring teachers to out transgender students to their parents if they begin using different names or pronouns at school. CVUSD’s policy mirrored a statewide bill proposed in the California State Legislature in 2023, which died after it failed to receive a hearing; the legislation proved nonetheless influential, with conservative lobbyists pushing copycat proposals at school boards throughout the state.

As we sit on metal risers beside the park’s baseball field, Kylie says she is exhausted at the mere thought of all this. She confesses that, if she’s being completely honest, she has never been all that interested in political activism. When it comes to the anti-LGBTQIA+ policies being enacted in other states, she is only aware of Alabama’s law limiting puberty suppressors and hormone replacement to minors because she has a friend there who is impacted by the legislation. “I can’t even wrap my head around all that,” she tells me.

As a toddler covers herself in sand from the baseball mound, Kylie explains that she feels enough pressure as it is without spending her time concerned that the realities kids in other states already face could soon disrupt her fantasy. While it might appear from the outside as if she’s got everything a teenage girl could ever want, Kylie is still completely and utterly terrified about nearly every aspect of her future – terrified she’ll be trapped in this moment forever, that she’s going to screw it all up. She lies awake at night counting as high as she can until she falls asleep, sometimes getting all the way to seven hundred before she tires herself out. She can’t be worried about being transgender, too, she asserts.

“I’m scared I’m not going to pass my classes,” Kylie says. “I’m not going to get into college. I’m literally going to be a flop. That’s what I worry about.”

It Gets Better… Except When it Gets Worse (And Other Unsolicited Truths I Wish Someone Had Told Me)

Nicole Maines is an award-winning actress, writer, and transgender rights activist. She was the anonymous plaintiff in the Maine Supreme Judicial Court case Doe v. Regional School Unit 26, in which she argued her school district could not deny her access to the female bathroom for being transgender and won, the first such ruling by a state court. That case and her family’s story was the focus of Amy Ellis Nutt’s bestseller Becoming Nicole. As an actress, Maines played Nia Nal/Dreamer on the CW’s hit series Supergirl and Lisa in Showtime’s Yellowjackets.

For the first time and in her own words, Nicole shares her own story from childhood in rural Maine to the spotlights of Hollywood, coming out to her parents and exploring the history that transgender people have always been here and have expanded our freedoms. Nicole also shares what she’s learned about the insidious messaging queer kids and all young women absorb about who they are and can be.

Chapter 5

Anyone who’s ever come out as anything knows that it’s not a singular event. It’s not like you get to just pick up a megaphone and tell the whole world, “You may have gotten it twisted somehow, but I’m a girl. I repeat, A GIRL, not a boy. That is all,” and move on with your life. It was a daily practice with my parents, neither of whom came to parenthood pre- equipped with a large frame of reference about gender-expansive kids. Whether or not they’re aware, everyone has queer and gender-expansive people in their lives, so I’m sure they did, too, before I came into their lives, but not in a way that either of them was really conscious of.

When I “came out” in 2000, there were precious few books about trans people in general, let alone trans kids. No one had heard of Jazz Jennings yet, one of the youngest people to identify publicly as trans in the modern sense of the word. She was inter- viewed by Barbara Walters on 20/20 when she was only seven, and she went on to host a YouTube series and a TLC reality show. No one had seen Laverne Cox on Orange Is the New Black yet. Mom had to do some very creative googling to even find the term transgender, which was still classified in the DSM as a men- tal disorder at that time. (It was declassified in 2013, thank yew very much.) It wasn’t until later when she saw Jennifer Finney Boylan’s interview with Oprah in 2003 that she found a resource that helped her gain an outside perspective of a trans experience. Jennifer was a particularly relatable trans person for my parents to contemplate: She’s much closer to their age than mine; she’s a professor, a parent, an author, and a powerful storyteller of her own trans experience. It doesn’t hurt at all that she grew up in Maine, as I would go on to do. Mom read Boylan’s book imme- diately and left it out for my dad to pick up. He studiously avoided it. Then one day, because my mom is a strategic wartime genius, she placed it in the bathroom where she knew he’d find it. The reason we still had so little information about trans peo- ple in the twenty-first century was because of fucking Hitler. I’m serious, it was fucking Hitler. Those assholes burned all of it.

But I’m getting ahead of myself, so let me back up.

Many people today see trans people as some new phenome- non. So much of anti-trans rhetoric is based on the idea that this is some sudden, unnatural fad. But you don’t have to be an anthropologist to figure out that there have been trans people as long as there have been people at all. In nearly every part of the world, there are cultures that hold space for trans, intersex, and multigendered people and have for generations. You know how pretty much every culture has their own kind of dumpling? Shu- mai, pierogi, wonton, what have you? Well, pretty much all the world’s cultures also have their own types of indigenous, deli- cious forms of gender diversity and saucy names for them on the side. There’s literally a Google map that pinpoints dozens of locations on the globe and highlights how those cultures have embraced the natural variation of gender in our species. The types of gender and sexuality standards and policing we’re famil- iar with in the United States were a colonial import for many parts of the world. Colonizers enforced their Christian ideology on colonized people, and one of the tenets of that ideology was gender conformity. Colonizers saw the variation in gender roles in other cultures as inferior and used it as an excuse to dehuman- ize and enslave and steal from them.

But there is written evidence from at least as far back as the nineteenth century that some European thinkers believed homo- sexuality and sexual variation were natural. In the early 1920s in Weimar, Germany, there was a doctor, Magnus Hirschfeld, who specialized in sexual health. Medical “common sense” at the time was that any form of gender nonconformity or homosexu- ality was straight-up pathological, but Hirschfeld argued that people existed all over what we usually refer to as the “natural spectra” of gender and sexuality. He was even sophisticated enough in his thinking to tell the difference between gender and sexuality—yet another thing that people can’t or won’t under- stand about trans people to this day.

He was the first to present statistical evidence that queers were and continue to be more likely to die by suicide or attempt sui- cide than heterosexuals. And he believed, like I did when I was three (not a brag, just a fact ), that modern science should be able to provide a way to transition if one’s assigned gender didn’t match their identity. He opened the Institute for Sexual Research in 1919, and by 1930 it performed the first modern gender-affirmation surgeries in the world and offered sex-ed classes and clinics and advice on contraception. He was a tireless legal advocate for queer and trans civil rights and worked to establish safe legal standing for gender-nonconforming people and protections from being arrested for openly dressing as themselves.

The institute housed an immense library on sexuality, gath- ered over many years and including rare books and diagrams and protocols for male-to-female surgical transition. Patients were provided with psychotherapy and prescribed hormone therapy.

Then Adolf Hitler was named chancellor on January 30, 1933, and he enacted policies to rid Germany of Lebensunwertes Leben, or “lives unworthy of living.” What began as a eugenic sterilization program ultimately led to genocide: millions of Jewish, Romani, Soviet, and Polish citizens—and homosexuals and transgender people—murdered in the name of racial purity. The Nazis came for the institute on May 6, 1933. Hirschfeld had already fled; he could see what was coming. Nazis swarmed the building, piling all the precious books from this unique library in the street. They lit more than twenty thousand books on fire, but more than that, they totally derailed Western cul- ture’s best path to understanding and healing from centuries of violent gender repression. It was among the first and largest of the Nazi book burnings. Even though the newsreels of it still exist, most people don’t even know that what they’re looking at is the remains of the world’s first trans clinic. The images on these reels are disturbingly familiar. All I can think of, as I write this very trans book you’re holding, is how the fascist political movement is on the rise in America today and is doing everything it can to ban books like this from schools, simply because they mention the existence of queer and trans people.

That’s why I personally dipped every page of this book in nitroglycerin during the production process. Go ahead and burn it, I dare you!

(The legal department said that I have to explicitly state here that that was a joke, and I did not, in fact, sabotage my own memoir with explosive paper.)

————–

Excerpt courtesy: From IT GETS BETTER… EXCEPT WHEN IT GETS WORSE: And Other Unsolicited Truths I Wish Someone Had Told Me by Nicole Maines. Copyright © 2024 by Nicole Maines. Published by The Dial Press, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Free to Be: Understanding Kids and Gender Identity

Internationally renowned child and adolescent psychiatrist Dr. Jack Turban brings the latest medical and scientific research to life with stories of transgender and gender diverse youth in “Free to Be.” Kyle, Meredith and Sam share how they navigate their gender identities and affirming medical and psychological care amid a chaotic political and social environment.

Free to Be also gives us tools to help kids in our lives with the complexity of gender identity, and guide us to better understand what the nuances of gender mean to ourselves and society at large.

Jack Turban, MD, MHS is a Harvard, Yale, and Stanford-trained child and adolescent psychiatrist and founding director of the Gender Psychiatry Program at the University of California, San Francisco. He is an internationally recognized researcher and clinician whose expertise and research on the mental health of transgender youth have been cited in legislative debates and major federal court cases regarding the civil rights of transgender people in the United States.

FREE TO BE – prologue

“If I ever knew someone was gay, I’d shoot them. Gay people don’t deserve to live.”

I was fourteen when my father said that. The sleeves of his flannel shirt were rolled up to his elbows, and I watched as a scowl burrowed deep into his shaggy brown beard. He was staring at the highway straight ahead, his hazel eyes narrowed and full of a rage I didn’t understand. There were two hours left in the drive back to my mom’s house. Country music filled the old Volkswagen Golf, punctuated by static from the weak radio reception of rural Pennsylvania.

I sat frozen on the passenger’s side. I knew he kept a handgun under his seat. And I knew I was gay. I looked down at the oversize khaki cargo shorts I wore to look straight. I turned my head toward the passenger-side window to hide any potential flush on my chubby cheeks. Was the comment directed at me, or did someone driving in front of him seem flamboyant? Did he know I was gay? Was I going to die?

I grew up terrified that if anyone found out I was gay, I would be kicked out of my house, beaten, or killed. I spent years trying to make myself straight. I took a girl in my middle school to an awkward movie date. I deepened my voice and stiffened my gait—two habits that I carry around to this day. I briefly joined the lacrosse team in high school and took a girl to prom. But it never worked. I couldn’t conjure up heterosexuality any more than I could conjure up the courage to accept myself. I eventually resigned myself to the idea that I would be closeted, and romantically single, forever.

Frustrated by my lack of progress in making myself straight, I spent countless hours thinking about sex and gender. What did it mean for me to be male and attracted to other men? What was sexual orientation? What was gender? Having suffered the psychological trauma of being told that being gay—something so fundamental about myself—was wrong, I was fascinated by the diversity of human identities and the stigmas attached to them. These interests, along with my hopes to escape Pennsylvania and my childhood, led me to study nonstop through high school. If I couldn’t have a romantic life, I’d be sure to have a thriving academic life. With my eyes laser-focused on escaping my situation, I joined every school club, took every early college class I could, and eventually made it to Harvard to study neuroscience. After that, I enrolled in Yale School of Medicine. I hoped that being academically successful would mean I could one day be forgiven for the fatal flaw of being gay.

I first came to the topic of how doctors should support transgender youth as a medical student. I had always been interested in writing, and Yale had a famous doctor-writer named Lisa Sanders on faculty. She wrote the Diagnosis column for the New York Times, which became the basis for the TV show House M.D. I emailed her, and she agreed to meet with me over coffee in the cafeteria.

When she sat down across from me with her coffee, my heart fluttered with intimidation. Her white coat engulfed her thin frame. Her cropped blond hair landed just above the glasses that painted the portrait of a seasoned no-nonsense physician. She got right to it, “What do you want to write?”

I explained that I was interested in how LGBTQ patients do poorly when doctors don’t understand them. I laid out a list of potential stories: the gay man whose sexually transmitted infection kills him because he was afraid to tell his doctor about being gay, a lesbian who is too afraid to tell her psychiatrist about the shame her sexuality causes her, and a short story about how doctors support transgender kids.

The last one caught her attention: “I don’t know anything about that one.” I could tell by the tone of her voice that she wasn’t accustomed to not knowing something. “What more can you find out about that one?”

While I started researching how doctors support transgender kids, Dr. Sanders taught me to approach the topic as a neutral journalist. Hear every side. Read every study. Unearth every piece of data you can. In between anatomy lab and lectures, I spent long hours studying in Yale’s Cushing Center—a room in the basement of the medical school library lined with famous neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing’s collection of brains in jars. Surrounded by these brains, and the faint pickle like smell of formaldehyde, I devoured the literature on what doctors thought about the mind and gender, and I found a shocking divide. Poring through dusty books and freshly printed journal articles in the dim lighting of the brain room, I learned that some doctors argued for therapy to push transgender youth to identify as cisgender. They said that gender identity was malleable early in life and that it was possible to “cure” kids of being transgender. They argued that this was good because you could save a person from needing medical interventions and surgery down the line. They didn’t say it explicitly, but it seemed clear they were also trying to save these kids from a future of living as a transgender person in a society that treated transgender people horribly. I reflected back: If I could have been made straight and avoided the pain of being gay in a homophobic society, would I have wanted that?

On the other side, doctors argued that trying to force a transgender child to be cisgender was dangerous and didn’t work. They thought it would instill shame in the child and lead to anxiety, depression, and maybe even suicide. They noted that the early years of a child’s life are important for establishing self-esteem, and that shaming children about themselves during that critical period could do lifelong damage to mental health. Those doctors recommended allowing trans children to transition young, if they wanted to, in a stepwise fashion from the most reversible interventions (changing their name or pronouns) to the least reversible (surgery) later in life.

The two sides seemed diametrically opposed: either support children in their transgender identities, including eventually letting them start puberty blockers and hormone therapy, or try to make them identify with their sex assigned at birth. Each seemed to follow reasonable internal logic, but clearly one had to be wrong. It scared me that one side was causing irreparable harm. But which side was it?

Over the next several years, I met physicians and psychologists from across the ideological spectrum and the globe, listening to what they thought. I also met countless trans people and scholars who shared with me their community knowledge and academic writings.

I jumped on Amtrak each month to visit the first clinic in the United States to offer puberty blockers and hormones for transgender youth. The Gender Multispecialty Service of Harvard’s Boston Children’s Hospital, nicknamed GeMS, let me spend time with their founder, a pediatric endocrinologist named Norman Spack. A gregarious man with a seemingly permanent smile between his gray goatee, he believed that being transgender wasn’t a condition of the brain, but of the body. He explained that for these young people, their bodies had betrayed them. They had an endocrine condition that prevented their bodies from developing in a way that matched who they knew themselves to be. So, he treated with hormonal interventions to correct it. He came to the field after spending time treating unhoused young people living on the streets in Boston, a disproportionate number of whom, he learned, were transgender. He heard their stories of being kicked out of their homes for being transgender. He heard about their struggles with gender dysphoria—a term for the psychological distress that results from your body not matching the gender you know yourself to be. Because no one else in the area was helping them, he convinced his hospital to let him open GeMS. He flew to Amsterdam, where physicians had started developing protocols for supporting transgender youth, and he brought their model to the United States.

In my studies, I also visited Amsterdam to learn from the doctors at the Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria at Vrije University Medical Center. While there, I met transgender youth and young adults who were thriving, supported by physicians who supported them with endocrine interventions.

On the other side of the spectrum, I met regularly with Dr. Ken Zucker, the gray-bearded, bespectacled psychologist who led the group that wrote the American Psychiatric Association’s criteria for “gender dysphoria,” a man who firmly believed that young transgender children could—and should—be made cisgender. He sometimes compared being transgender to a delusion, once asking me, “I had a kid tell me the other day that he thinks he’s a fox—we wouldn’t make him into a fox, would we?”*

* It’s worth noting that by the time I met him, Dr. Zucker supported puberty blockers and gender-affirming hormones for many transgender adolescents. His efforts to push trans youth to identify with their sex assigned at birth seemed to be confined to prepubertal children.

Over the years, I met transgender kids from around the world—some of whom were accepted for their gender identity—and many more who were rejected for it. I also began my own research, using large datasets to investigate what predicts good and bad mental health outcomes for young transgender people. Completing my adult psychiatry training back at Harvard, I cared for transgender adults—those who were thriving because they were accepted, those who were struggling with ongoing harassment and the challenges of getting access to gender-affirming health care, and those who were still navigating the difficult feelings that came from transphobic things they heard from their parents when they were young. After residency, I completed my subspecialty training in child and adolescent psychiatry at Stanford, where I sat with young kids who were exploring their gender identities, and their parents, who didn’t know what to do but desperately wanted their kids to live happy, healthy lives.

Today, I write from my office at the University of California, San Francisco, where I direct the Gender Psychiatry Program, our clinical and research program for helping young people and their families navigate the complexities of gender and the way society treats those who don’t live up to our traditional gender expectations.

It has been nearly a decade since I started studying kids and their gender identities. The politics of gender have exploded, while most of the research and data about gender identity have remained hidden away from mainstream public knowledge. It’s a vital time for people to be educated. The science of gender has huge implications not only for medicine and psychiatry, but also for how we understand ourselves, our children, and society at large. As we dive deeper into the complexities of gender, we often learn a lot about ourselves—that our own gender identities are more nuanced than they appear at first glance. We also learn a lot about society and politics. Now more than ever, gender has exploded in the political arena, with legal implications for everything from medical regulation, to education policy, to sports. Whether you’re a parent, a policymaker, a scientist, a health care worker, a therapist, a teacher, or someone just trying to better understand yourself and the people around you, comprehending gender at a deeper level will open your eyes to how we can all work to create a safer, more compassionate society at every level.

Adapted from FREE TO BE: Understanding Kids & Gender Identity, Copyright © 2024 by Jack Turban, MD published by Atria Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. LINK

A Place for Us – A Memior

In his powerful and inspiring memoir, Brandon J. Wolf describes his journey from a young queer outsider to nationally-known activist and leader. In this emotional excerpt, Wolf describes returning to the Pulse nightclub in Orlando after surviving the devastating shooting that violently took the lives of 49 people, including his best friend. Wolf explores how to get through the darkest times with healing, hope, and resistance, and to honor lives with action – for safety, for equality, for each other.

Brandon J. Wolf is a nationally recognized public speaker and advocate for LGBTQ+ civil rights and gun-safety reform. He serves as National Press Secretary for the Human Rights Campaign.

Excerpt

The early-summer sun was beating down by the time we arrived at Pulse. Beads of sweat had formed above Dad’s unkempt brows. Ripples of heat radiated up from the asphalt. In a nearby tree, a few cicadas buzzed loudly, their tune unchanged by the hallowed ground beneath them. The site was empty and still, the dark towering walls of the club tucked behind a chain-link fence encased in black fabric. Along the fence, people from across the world had placed flowers and gifts in honor of the lives that had been stolen inside. Plastic pinwheels and rainbow flags, once crisp and vibrant, had faded under the harsh glare of the Florida sun. We walked slowly past the bits of memorabilia: photos left behind by loved ones, birthday cards, Christmas gifts. The joyful smiles of the victims frozen, as if no time had passed at all. Dad was stoic. He always kept his emotions tightly bottled, loath to show cracks in his tough, battered armor. Through the dark tint of his sunglasses, I could see him squinting to take it all in. He paused at a poster with the names and pictures of the forty-nine victims, scanning each one carefully.

The infamous sign near the edge of the property had been transformed into a community message board with notes and words of love. Dad picked up a fine-point marker and scribbled a few words on the worn paint. I couldn’t make out what it said, but it didn’t matter. That he thought to write anything was enough. We walked slowly from one end of the lot to the other, pausing occasionally as I explained how it had been before the tragedy. I took him to the back of the building, peeking through a hole in the fence at the place where police used explosives to breach the walls and free hostages huddled around leaky toilets. I showed him the route I had taken, where I knelt on the sidewalk and called him just before 3:00 am. I pointed through a split in the fabric at the exit through which I had escaped that night, its doors still riddled with bullet holes. All the while, his demeanor remained unchanged. His lips were pursed, his brow deeply furrowed.

As we made our way back toward the car, he stopped at a photo of Drew and Juan that hung from the fence by two zip ties. He lingered on their blissful grins, their innocent happiness still palpable despite the weathered paper. I could see that, for the first time, he was processing what it must have been like for them. For me. I wondered what he thought about all of it. Was he trying to imagine the horrors of that night? To comprehend what their deaths sounded and smelled like? Was he trying to picture what it must have been like for me, crouched against the wall, listening to a hail of gunfire outside? Could he hear the wails of other parents howling like wounded dogs? Was he sad? Mad? Or just struggling with the overwhelming inability to articulate a potent cocktail of emotions?

We slid into the car and clicked the doors closed behind us. The rush of cold air from the vents provided relief and some sound to interrupt the silence. I glanced over to see a single tear falling down Dad’s cheek. I’ve always considered his hardened exterior to be a strength. He’s not overcome by things like I am. He finds a way to grit his teeth and pull through anything, holding the family together by shoestrings when it seemed inevitable that we’d come apart at the seams. He used to scoff when I would burst into tears as a kid, barking at me to “cut the water works” and storming out with a huff. But here in the car, he was refreshingly human. At his request, we’d come to my most vulnerable place, and he didn’t revert to the man I had once resented and often feared. He allowed himself to be vulnerable alongside me, exposing his pain as if it were an offering of peace and reconciliation. I instinctively looked down at my hands, a reflexive attempt to avoid getting caught staring. I wanted him to know how much I appreciated him while still allowing him the space to feel it all. I started the ignition, determined to let the silence persist if he needed it. But before we could pull away, he cleared his throat.

“Son,” he said, his voice wavering. “I am so sorry you had to go through this. That your friends had to go through this. I know I said and did things, when you were a kid, that were hurtful. Truthfully, I was scared. Scared that the world wouldn’t understand you. Scared that the world would hurt you. I realize now that I wasn’t ever going to stop bad things from happening. I just ensured that when those bad things happened, you didn’t feel like you could call me first.”

My understanding of forgiveness has evolved over time. Sitting at a countertop, across from a film director, I learned that forgiveness is not just an olive branch we extend to others, but a necessary first step to healing ourselves. And sitting with my father, the man I harbored the most resentment toward, I understood forgiveness to be not a dismissal of past harm, but an offer of grace and a chance to create something new. I used to hold onto toxic grudges because I wanted people to pay for what they had done, and forgiving them felt like injustice. But in truth, offering them grace allowed me to lift from my shoulders the burden of what had been in order to leave space for what could be.

In a moment of intense vulnerability, as a cold blast of air conditioning dried the tears on our cheeks, I forgave my dad. He didn’t ask or expect me to. I can’t remember if I’d ever said those words — I forgive you — to him before. But I made a choice that day to refuse to carry the weight of our rocky relationship anymore. Every one of us is human. We make mistakes. We fail. We learn. We grow. We hurt people. Sometimes we go back to make things right, and those times have to mean something. When I talked back to my mother, defiantly wagging my finger at her, she forgave me. When I lashed out at Drew in a fit of jealousy, my drunken rage bubbling over in a crowded nightclub, he forgave me too. Because forgiveness is not just an offer of grace — it is a powerful act of unconditional love.

Forgiveness is hard and messy. Sometimes it’s two steps forward. Other times, three steps back. But it offers a deeply powerful beginning that can chart a whole new path forward.

I don’t know how many more birthday cards I’ll get from Dad before he’s gone. I don’t know how many more monogrammed Christmas gifts will come in the mail. But I know that life is terrifyingly short. And though Dad wasn’t entitled to it, forgiving him was a necessary step toward realizing the full power of my own potential.

He hurt me over the years. Sometimes in little ways: unnecessary disappointment over a single B on my report card, irritated combativeness when I couldn’t keep up during a political debate. Other times, he cut more deeply. The way he rejected me when I was at my most vulnerable as a queer teenager spiraling out of control. His sharp tongue when I dared to challenge him, the words he chose slicing like a knife. His inability to see how isolating it was for me to wander the world alone, a half-Black kid called “Oreo cookie” and “little monkey” at school, without anyone to tell me how to condition my curly hair or moisturize my ashy elbows. His thick emotional shell – a survival mechanism constructed to protect himself after Mom died – that kept him from hugging me as often as I needed. We talked past each other for years, and I held a grudge for even longer. But it was time to let go. We were grown men, with more than a lifetime of lessons learned between us, finally willing to let down our guards in a quiet bit of honesty. We weren’t sparring minds anymore. We were simply father and son, an imperfect family, content to be just that — a family.

I let out a sigh and choked back a decade’s worth of tears.

Dad turned to me, now beaming with pride. “I love you, son.”

And I believed him.

Pritty

The sensuality of Frank Ocean meets the rhythm of Toni Morrison in Pritty, a debut novel by Keith F. Miller Jr. that follows two boys who get caught in the crossfire of a sinister plot that not only threatens everything they love but may cost them their chance at love.

Keith F. Miller, Jr. is an award-winning educator, artist, and researcher who studies healing literacies and their role in supporting BIPOC and LGBTQ+ communities in healing, growing, and thriving through trauma. He has an M.F.A in creative writing at St. Francis College in Brooklyn, NY. Pritty is his debut novel.

CHAPTER 1: JAY

It’s Leroy, and I think he’s going to kill me. So I do the only thing I can: swing first. Well, not exactly. I’ve never fought anyone, except my older brother, Jacob, and even those couldn’t be called fights. They are more like physical arguments that turn into one-sided tantrums I lose before a single punch is thrown. But Jacob did teach me one thing after I failed miserably at learning to throw a football straight (never happened), to hit a baseball (not even off a tee), or to dribble a basketball (does carrying the ball with two hands count?): how to tackle and run.

Honestly, I don’t know how I could have done anything to Leroy; I’ve always kept my distance, steered clear of him and the crowd vying for his attention, whenever he would drive by. When I heard a couple of guys say he’d been asking around about me, I thought it was a joke. I’ve only ever heard rumors about him, since we don’t even go to the same school. I couldn’t think of any reason why he—the younger brother of Taj, one of the leaders of the Black Diamonds who reign over K-Town—would want anything to do with me, so I said, “Whatever,” and walked off.

How was I supposed to know he was really looking for me?

I think about making a run for it since we’re next to a makeshift field in the back of a church, a shortcut I always take home on the way from school. If I run left, he could push me into the canal. If I run right, there’s only woods, and I’m far from anybody’s Mowgli. If I run in the opposite direction, he’s close enough to grab me, which means the only way out of this is forward, through him, by any means necessary.

I remember Jacob’s words: lower your stance, shoulders down but back, and then—as fast as you can—explode forward while pushing up. I charge toward him with everything I have, fearless and fear-full at the same time.

When I crash into Leroy, I smell peppermint gum and Cool Water cologne, but he doesn’t fall. Instead, he crouches low and holds fast. Pushing and pulling, we grasp for legs and ankles to take each other down. He smirks, as if me fearing for my life is amusing. Then, I take my chance.

With all my weight, I pull him close in a tight embrace and then barrel forward, throwing us both off-balance. We topple over Spanish-moss-covered tree roots that punch our bodies like iron fists in satin du-rags until we land in a bed of pissed-off twigs.

On top of him, I flail could-be punches with great effort and little form. Beneath me, his arms are right angles that dodge and slap away every blow. He chuckles, but I am serious. Every closed- and open-handed hit that makes contact whispers a fervent prayer to whatever god will lay away me a miracle, because I need it. I’m not stupid; I know damn well Leroy is bigger, tougher, and faster. If the rumors are true, he’s also dangerous, like his older brother. I just need to escape so I can run home and never look back.

“Aye . . . yo . . . aye . . . ,” he repeats between swats, grabbing at my hands and wrists. Suddenly he smiles, and then lifts me up with his hips. I lose my balance and fall to the side. He climbs on top of me, but he’s let his guard down.

Slap! The sweat on his face licks fire into my palm—I hit him hard.

Leroy glares, and in one quick motion, he slams me into the ground. “Chill,” he says. I thrash about as hard as I can and barely graze his face.

“I said chill,” he yells. Leroy catches one of my wrists and dodges a punch from the other. I clutch at his throat but miss. I claw at his face and miss again.

Leroy finally grabs both of my wrists and pins me down. “Are you deaf? I said chill out!” He growls the words into my neck.

Sweat drips from his face and arms, which glisten even in the shadows of the trees. A silver chain dangles in the space between us, against the backdrop of a tattoo peeking from the top of his white beater. Something stirs in my chest, a different kind of fear. My body freezes. I hold my breath without knowing.

“You gon stop tryna hit me?” he asks.

F— you, I whisper over and over in my head.

No matter how this ends, I won’t give him the satisfaction of hearing me utter another word. His eyes soften. “Aight, I’m bout to let you go, but you hit me again, you aint gon like what I do.”

I believe him.

He loosens his grip, but our bodies are too close for comfort; my shorts are hiked up in the scuffle, waist and thighs exposed. Somewhere between us, the friction lights a spark. And in the stillness, our bodies are a cocked gun, our labored breaths are fingers stroking the trigger. I try to pull away, but the more I move, the bigger it grows.

He looks down, jumps up, and turns away, tugging at the front of his basketball shorts. Before he can say anything else, I scramble to my feet and run down the field toward the church. I hear him behind me yelling, “Jay . . . Jay . . . I didn’t mean . . . I just . . . ,” but I keep running past the parking lot until I’m out of sight.

I don’t run home; I double back and hide between the pink azalea bushes at the front of the church and watch him. For a while, he stands there looking in my direction, his disappointed silhouette ablaze in the blushing sun.

Even after Leroy walks away, I stay, drowning in questions while standing up. Every muscle throbs, wound tight like a fist, waiting for him to jump out the nearest bush of pink azaleas for round two. In my mind, we clash into each other again and again, unafraid, until our bodies are a breath on the cusp of a moan.

I dust off my school uniform as best I can. Get all the leaf bits and twigs until only the faint scent of fight and dirt and close calls and shame cling to the tattered seams of my khaki shorts. I walk until it all makes sense, which means until my calves ache, my mouth goes dry, and the bottom of my feet burn. Until the only sense to be made is that I’m f—ing tired and I have no f—ing idea what the f— happened or what it means. I want to know why I still feel the heat of his palms, the weight of his body pressing down just hard enough that I know it’s there.

When I see the chain-link fences and hear basketballs licking palms and headbutting hot concrete, I know I’ve walked too far. I’m on the other side of Reeds Gate, somewhere near the lip of Peach Street. Any farther and I’ll cross the train tracks into K-Town, where I’m not allowed to go unless Jacob walks with me. Across the street, the “City Kitty” bus hisses and then curses as it kneels near an orange bus pole with letters scraped off, so it reads, “Bop.” When the bus huffs away, all that’s left: an old man on the corner clutching a brown paper bag, sipping and singing to the cars.

I turn around and walk back until I stare at home. Jacob and Momma haven’t made it in yet—and won’t since both work until late in the evening. Relieved, I file away the story I concocted in my head. I don’t want Jacob or Momma to know what happened between me and

Leroy because it will only lead to more questions. I want to keep it to myself because I don’t know enough of the truth to trust it, to risk whatever meaning might be waiting for me on the other side.

I walk through the front door and plop onto the couch but eventually get up and reheat the lasagna Momma must have cooked before she left for work. I scarf it down, outrunning the thoughts replaying me and Leroy wrestling. Afterward, I fall asleep waiting for something, anything that can answer the questions I’m too afraid to ask.

Pritty has been shortlisted for the Lambda Literary Award in YA Fiction. The winner will be announced in June. The sequel, Togetha, will hit shelves in January 2025.

Friday I’m in Love

Friday I’m in Love is a love letter to romantic comedies, sweet sixteen blowouts, Black joy, and queer pride.

Mahalia Harris wants a big Sweet Sixteen like her best friend, Naomi. She wants the super-cute new girl Siobhan to like her back. She wants a break from worrying—about money, snide remarks from white classmates, pitying looks from church ladies . . . all of it.

Then inspiration strikes: It’s too late for a Sweet Sixteen, but what if she had a coming-out party? A singing, dancing, rainbow-cake-eating celebration of queerness on her own terms.

Author Camryn Garrett grew up in New York and began her writing career at thirteen, when she was selected as a TIME for Kids reporter, interviewing celebrities like Warren Buffett and Kristen Bell. Since then, her writing has appeared on MTV and in HuffPost and Rookie magazine, and she was recently selected as one of Teen Vogue’s “21 Under 21: Girls Who Are Changing the World.” Camryn is a proud advocate for diverse stories and storytellers in any medium. Friday I’m in Love is her third novel and first rom-com.

Excerpt

Thank God the big, ornate columns of the restaurant are coming up on the left—an all-white building right on the water. Gigantic windows look out over the beach. It’s the type of venue only Naomi’s parents could afford. The type of venue I wish I could’ve had for my nonexistent party.

But it doesn’t matter anymore. It’s too late for me to have a Sweet Sixteen and there’s no such thing as a Sweet Seventeen. The next-best big party to look forward to is, like, a wedding or funeral.

Mom stops in front of the restaurant and I’m pretty sure I’m gaping. There are people dressed up in uniforms, taking coats and parking cars. It’s crazy.

“Be good,” Mom says, pinching my cheek. “I don’t want to hear that you were being

disrespectful to Mr. and Mrs. Sanders. Understand?”

I stick my tongue out at her. She’s mostly kidding—I’m at Naomi’s house all the time and I’m pretty sure I see her parents more than I see my own mother, but I don’t say that. It’s not her fault that the nursing home gives her these insane hours. She’s wearing her scrubs now, and for a second, my brain flashes forward, seeing the way she slowly shuffles into our apartment after a twelve-hour shift like she hasn’t had the chance to sit all day.

“Mahalia?”

People dressed in high heels and suit jackets are already heading inside. I barely

recognize any of the faces, but I’m pretty sure they don’t shop at Forever 21. My spine stiffens.

This isn’t going to be like hanging out at Naomi’s house after school. Mom nudges me forward. “Be good,” she says again as I open the door. “I love you.”

“Bye, Mom.” I force myself to swallow. “Love you, too.”

I step out of her beat-up car and don’t look back.

When Naomi and her parents first started planning her party, I was so excited, it could’ve been my own. I wanted to go with her to try on dresses and pick out invitations and talk about what music she’d play. Along the way, I guess I forgot that I wouldn’t be the only guest here.

Naomi is my best friend, but she’s a lot better at the social part of friendship. I know a lot of people because we go to school together, but they’re not exactly friends—more like people I’d be lab partners with.

This room is full of potential lab partners. Naomi has friends of different races and

genders and ages. There are round tables draped in white cloths where people nibble on appetizers. Then there’s the big wooden dance floor, where a few brave souls are trying to get things going.