Since 1990, The Association of LGBTQ+ Journalists (NLGJA) has met annually as a group to network and share best practices for fair and accurate coverage of LGBTQ people in and outside of newsrooms. This year, from September 4-6, Midtown Atlanta served as home base for hundreds of LGBTQ journalists and allies from across the country eager to utilize LGBTQ storytelling to accelerate acceptance, combat misinformation, and elevate underreported stories in an increasingly hostile political climate for LGBTQ people.

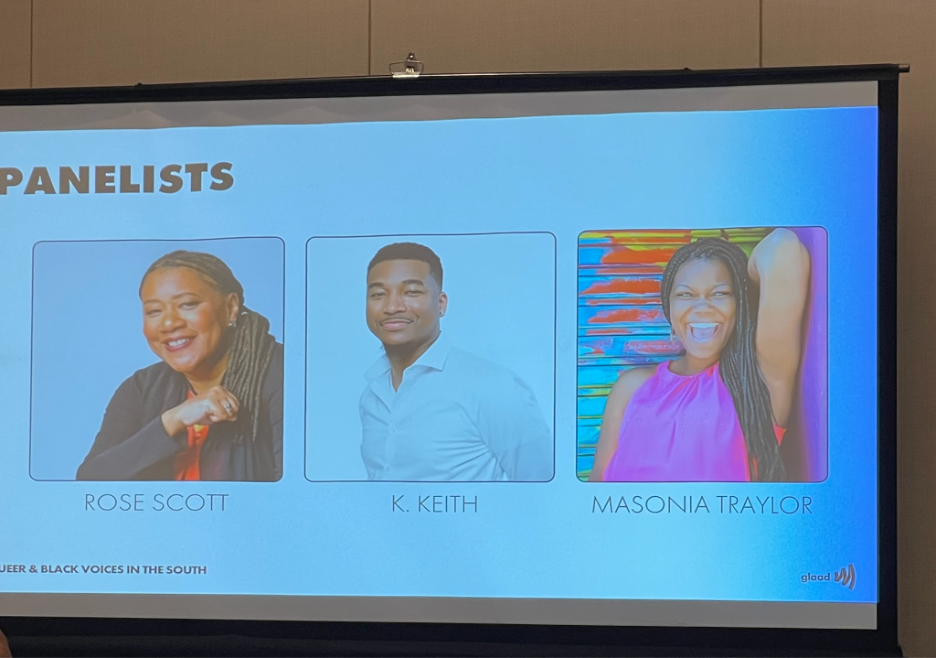

Capitalizing on the convention location in the South this year, GLAAD’s Director of Local News U.S. South, Darian Aaron, led a panel to share expertise and experiences covering Black and queer Southern stories. Queer and Black Voices In The South: Reporting Through An Intersectional Lens featured panelists including legendary Atlanta NPR journalist Rose Scott, K. Keith, Editor-in-Chief of GAYE Magazine, and Masonia Traylor, Global HIV Advocate. The hour-long discussion centered around underexplored Black LGBTQ stories, newsroom diversity, and accurate and inclusive storytelling.

“The U.S. South is home to the largest Black and LGBTQ populations, yet it is also the U.S. region most resistant to LGBTQ equality,” Aaron said. “Atlanta is commonly referred to as the Black Gay Mecca. Still, the stories told about Black LGBTQ people from this region in mainstream news, and even sometimes in queer outlets, often fail to reflect the rich diversity and dynamic storytelling found inside these communities.”

GLAAD’s Local Media Accountability Index U.S. South, released in 2021, researched 181 local media outlets, both print and broadcast television, across 10 Southern states and found 39 of the 181 produced zero or negligible LGBTQ content over 18 months. At least one outlet in every Southern state studied did not produce an LGBTQ-related story, had extremely limited stories about people living with HIV (the US South has the highest rate of new HIV diagnoses), and 12 outlets in Mississippi did not report a single LGBTQ story. Through GLAAD’s investment in local news, Aaron turned the LGBTQ story deficit around with local news placements featuring LGBTQ people in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and the Carolinas. But there is still more work to be done.

“We have a moral responsibility as journalists to do what’s right,” Keith told those in attendance, before sharing how he and his team decide on the type of content to post for their growing audience of nearly 300,000 followers on Instagram.

“With our coverage, we show the good, the bad, and the ugly because it’s necessary, but we do it with integrity,” he said.

Panelists challenged old-school journalism notions requiring “both sides” when reporting LGBTQ narratives. Keith, Scott, and other queer journalists see zero value in providing a platform for disinformation rooted in anti-LBGTQ bias.

“My job is to be fair, not objective. It’s a big difference,” said Scott. “ I’m not bringing someone on the show just because they have a difference of opinion and they want to spew a bunch of hatred. My platform is to offer credible, timely, relevant, respectful dialogue, and that’s what I look for,” she added.

It’s about the human experience

Channeling Black civil rights icon Malcolm X, Keith reminded the audience of journalists of the power they hold when telling another person’s story.

“The media is the most powerful entity on earth,” Keith said, quoting X. “They have the power to make the innocent guilty, and to make the guilty innocent, and that’s power. Because they control the minds of the masses.”

Masonia Traylor, a heterosexual Black woman and LGBTQ ally who has spoken on domestic and international stages about living with HIV for nearly 15 years, shared her experience of a journalist who irresponsibly reported her story and the lasting impact it had on her life.

“The first time I ever shared my story was at Spelman College, and The Atlanta Voice captured and published it,” Traylor said. “And then, other newspapers started contacting me. The second time was with CNN. I was very unprotected in that moment. I was not coached. I was not told what to say or how to say it. That story painted me as an irresponsible young woman, who had a child as a teenager, on Medicaid, and not practicing abstinence—basically, a welfare queen,” she said.

Traylor notes that it wasn’t until she had an opportunity as an undergraduate student at Georgia State University that she was able to make steps toward correcting the story when journalists from The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and CNN, including a then-new CNN editor, visited her non-profit leadership class.

“I got to express to her in a room full of 100 to 200 students that your [CNN] team failed me,” Traylor said. “I asked that editor to change that story because what you’re sharing with the people that I know is that you have to be irresponsible to contract HIV. And I was like, that’s not what happened. What is this story telling?”

At that moment, Traylor said she was” reminded of the power of speaking to an editor willing to listen.”

“She went back and edited the story,” Traylor said. “That took seven or eight years, but I hadn’t let it go. “There is a social responsibility for how a story is being told. Everyone asks, ‘Well, how did you get it? What happened?’ And I begin to say, to de-stigmatize the LGBTQ community and HIV, that I got HIV from choosing to love a Black man who did not prioritize his health. “It’s not just about sexuality, it’s about the human experience.”

And that experience, Scott reminded the audience, includes LGBTQ people.

“At the end of the day, we cover people,” she said. “And the last time I checked, people included LGBTQ folks, right? That’s it. We cover people. And if [news] leadership asks, ‘Why should we cover?’ Because they’re people and this is an issue.”

According to Keith, reporting Black LGBTQ stories accurately and consistently can often be a matter of life and death for the interview subjects, with unexpected impact on the journalist telling the story. For Keith, who courageously shared a 2021 video of a then 12-year-old queer child suffering horrendous abuse by his parents, who shaved the word gay into his head as punishment for his sexuality, the assertion is not hyperbole.

“It triggered me to see someone being abused, especially a young child,” Keith said. “It immediately touched me. Because I was already in community with activists and leaders who were already doing the work on the ground, and because those people followed me and respected the platform, they shared it,” he said.

Keith tells GLAAD that queer advocate and former Atlanta City Council candidate Devin Barrington-Ward shared the video with a local TV news outlet directly from his Instagram page.

“That blew my mind,” Keith said. “[The parents] actually got arrested. We reported on it from the beginning to the end. I was fearful they might come after me because I’m the one who blew up the story. Sometimes, that is the risk you take as a journalist. But it’s important to know that I saved a life. I changed this child’s trajectory because they don’t have to be in that environment anymore.”

“It is imperative that the challenges and triumphs of LGBTQ people of color and people living with HIV are not categorized as niche coverage but are viewed as another complex and dynamic aspect of the Black Southern experience deserving to be told,” Aaron said. “Scott, Keith, Traylor, and other fearless queer journalists and advocates exemplify the perseverance required to exist as a marginalized person in the South, and the audacity required to push media outlets to find value, not only in LGBTQ stories, but also in the people at the center of those stories.”