As we round out October with LGBTQ History, it’s important to note the amount of BIPOC Queer History that has been an integral part of American history but has unfortunately been largely erased. Queer history surrounding people of color is deeply interwoven with American history, revealing critical insights into the nation’s progress in civil rights, social justice, and cultural evolution. To understand American history fully, it’s essential to acknowledge how Black queer individuals have shaped and influenced pivotal movements, art, and thought in the U.S. Despite facing intersectional challenges related to both race and sexual orientation, Black queer Americans have persistently fought for visibility, acceptance, and equality, contributing a legacy that has strengthened America’s commitment to inclusion and diversity.

Black queer history includes significant contributions to American arts and culture. From the Harlem Renaissance to contemporary music and fashion, Black queer individuals have played central roles in defining American aesthetics and storytelling. The Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, for example, was driven by several Black queer artists, including poets like Langston Hughes and novelists like Richard Bruce Nugent, whose works celebrated Black identity while also subtly addressing queer themes. These artists expanded narratives around Black life in America, blending the experiences of race and sexuality into a singular, expressive voice.

The contributions of Black queer Americans to political activism are also inseparable from American history, especially when considering the origins of LGBTQ+ advocacy. These activists confronted police harassment and societal prejudice, laying the groundwork for the LGBTQ+ rights movement in the U.S.

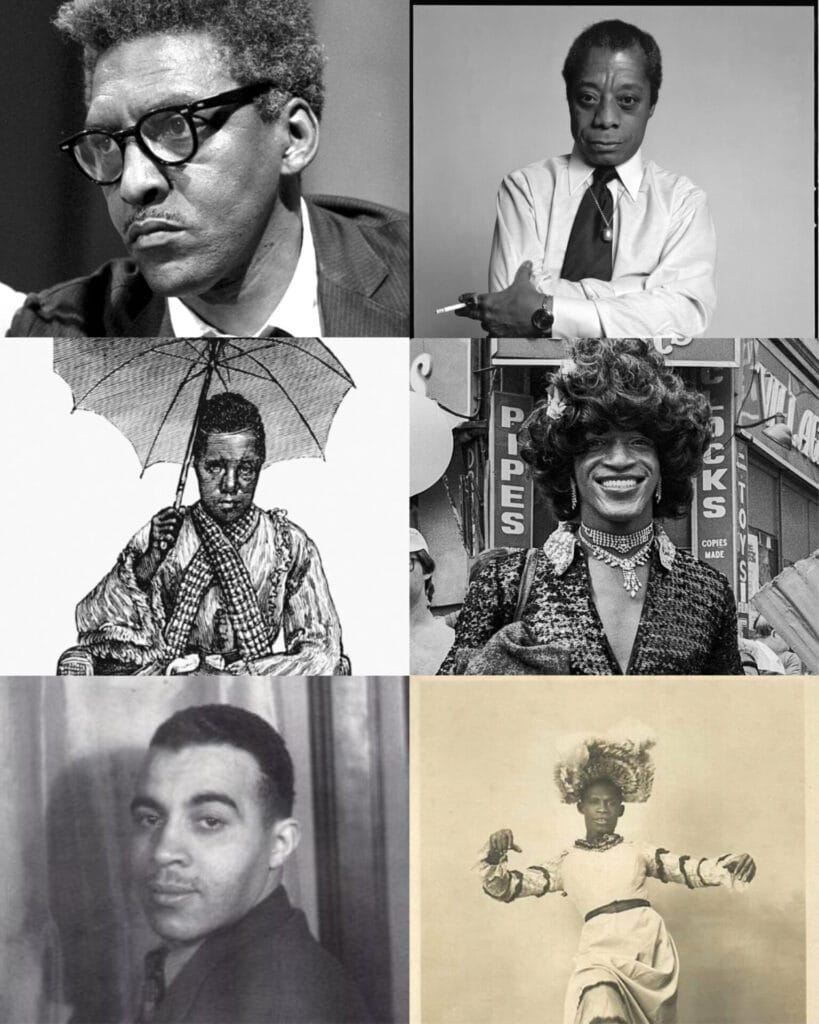

William Dorsey Swann

William Dorsey Swann was the first drag queen. Swann was born into slavery in Maryland just before the Civil War. In the 1880s, as a young adult, he moved to Washington, DC to find work to help support his parents and siblings. In Washington, he found the Emancipation Day parade, an enormous annual celebration commemorating the end of slavery in the US capitol. The highlights of the parade were called queens: Beautiful, crowned Black women who personified African-Americans’ newfound freedom. The queens of Emancipation Day so inspired Swann, that he adopted the title “queen” for himself at the secret dance that he and his friends called “a drag.” The word “drag” possibly comes from a contraction of “grand rag,” which is an early term for a masquerade ball.

Stated by the National Museums Liverpool, “Swann consistently resisted the censorship of their drag balls and continued to organise and hold events in Washington D.C. for several years. Swann was sentenced, in 1896, to 10 months in prison for the false charge of ‘keeping a disorderly house,’ also known as a brothe.l” That made Swann the earliest documented American activist to take steps to defend the queer community. But of course, the authorities couldn’t stop Swann and it especially didn’t stop Balls from continuing to expand to other cities. Today, queer drag is mainstream. From “Pose” to “RuPaul’s Drag Race” and the houses of 21st century ballroom culture, with queens who preside over beauty and dance contests, have maintained the same basic structure as Swann’s 19th-century community.

Marsha P. Johnson

Marsha P. Johnson was a Black transgender woman and activist and was a central figure in the Stonewall Riots of 1969, which ignited the LGBTQ+ rights movement. Born in 1945 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Johnson moved to New York City’s Greenwich Village at age 17, where she found community among other LGBTQ+ individuals. Known for her vibrant personality, distinctive flower crowns, and colorful sense of style, Johnson became a beloved figure within the LGBTQ+ community and an enduring symbol of resistance against injustice.

Along with Sylvia Rivera, a Latina transgender activist, Johnson co-founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) in 1970, an organization dedicated to providing housing and support for homeless LGBTQ+ youth. STAR became one of the first LGBTQ+ organizations in the U.S. to focus specifically on transgender issues. It pioneered a legacy of advocacy for transgender and gender-nonconforming people who were often overlooked by mainstream gay rights organizations.

Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin was a gay Black man who was a chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, one of the most iconic events in the Civil Rights Movement, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his historic “I Have a Dream” speech. Rustin’s organizational skills, strategic thinking, and commitment to nonviolent protest were instrumental in bringing over 250,000 people to the Lincoln Memorial in a peaceful and powerful demonstration for civil rights. Rustin also introduced King to the principles of nonviolent resistance, drawing from his own experiences working with pacifist leaders and the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi.

Many leaders saw his open homosexuality as a liability that could be used by opponents to discredit the movement. He was often forced into the background, where he worked tirelessly but with little public recognition. Nonetheless, he continued to advocate for civil rights and social justice and never wavered in his commitment to both causes, embodying the idea that justice must be intersectional.

Later in life, Rustin became an advocate for LGBTQ+ rights, recognizing the connections between the struggles for racial and sexual equality. He spoke out against homophobia and worked to bring visibility to LGBTQ+ issues, particularly those affecting LGBTQ+ people of color. His activism foreshadowed today’s understanding of intersectionality, emphasizing that true equality must address the overlapping oppressions faced by individuals at the intersections of race, sexuality, and other identities.

Frances Thompson

Frances Thompson was a formerly enslaved Black transgender woman who became a significant figure in the post-Civil War South. She is one of the earliest known trans women to testify before Congress whose harrowing congressional testimony about the Memphis race riots of 1866 helped shape the course of Reconstruction and galvanized support for the 14th Amendment, which provided Black Americans with citizenship rights and the promise of equal protection. Historian Channing Gerard Joseph recounted with Mills Performing Arts that Thompson’s testimony, “one of the linchpins in getting the political will together to pass legislation to protect the civil rights of newly emancipated Black people and also to bring political will behind Reconstruction after the Civil War.”

In 1866, Thompson and a friend, Lucy Smith, both Black women, were victims of a brutal assault during the Memphis Riots. These riots were fueled by racial tensions and erupted into violent attacks on the Black community by white mobs, including former Confederate soldiers. Thompson and Smith testified before Congress about the assault, bravely detailing the violence inflicted upon them. Their testimony was significant because it provided firsthand accounts of racial and sexual violence against Black women during a time when such injustices were often ignored or minimized by the legal system. Thompson’s testimony ultimately contributed to the investigation of the Memphis Riots, revealing the intense hostility faced by Black people in the South and putting national attention on the need for protections for newly freed Black citizens.

James Baldwin

Born in Harlem in 1924, Baldwin became one of the first Black authors to write openly about homosexuality, challenging societal norms and sparking conversations about the intersection of race and queer identity. His contributions are seen as foundational to understanding queer experience in America, especially for queer people of color.

Baldwin’s 1956 novel, Giovanni’s Room, broke new ground by centering a story around same-sex love. Though the novel’s characters were white—partly due to concerns about public reception—Giovanni’s Room remains one of the earliest and most powerful literary explorations of gay desire and identity, particularly amid the homophobia of the 1950s. Baldwin’s depiction of the protagonist’s struggle with his sexual orientation resonated deeply with readers and became a classic work in LGBTQ+ literature, marking Baldwin as one of the first Black authors to address same-sex relationships with unflinching honesty.

In addition to his fiction, Baldwin wrote numerous essays that delved into his personal experiences as a gay Black man in America. In essays like “The Fire Next Time” and “No Name in the Street,” Baldwin discussed his experiences with racism, religious conservatism, and the dangers of societal repression. He argued that homophobia and racism were both forms of oppression aimed at controlling people’s identities and limiting their freedom. Baldwin believed that addressing these intersecting forms of prejudice was essential to building a more just and inclusive society. You can find his interview with Richard Goldstein, “Go the Way Your Blood Beats” published in The Village Voice (1984), contains his best-known statements on sexual minority rights, nomenclature, and his own life. You can read the interview along with other conversations in James Baldwin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations.

Baldwin’s visibility as a gay Black man was especially impactful in a period when both racial and LGBTQ+ issues were emerging as critical areas of social justice. He became a mentor to civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and was close friends with Medgar Evers and Malcolm X.

Richard Bruce Nugent

Nugent’s most famous work, Smoke, Lilies, and Jade, published in 1926, is one of the earliest known literary works by an African American to feature same-sex desire openly and unapologetically. The story, a semi-autobiographical narrative written in a stream-of-consciousness style, tells the story of Alex, a young Black man exploring his attraction to both men and women. In depicting same-sex love, Smoke, Lilies, and Jade broke significant ground by challenging the boundaries of sexual identity and freedom in a time when such themes were rarely, if ever, publicly acknowledged within Black or mainstream literature. Nugent’s willingness to address queer themes so directly helped set the stage for future generations of Black LGBTQ+ writers and artists.

His open expression of his sexuality made him something of an anomaly in Harlem’s creative circles, where many queer Black artists often concealed their sexuality due to the social climate of the time. Despite this, Nugent maintained a presence in the movement and, together with his peers, expanded the narrative of what it meant to be Black in America.

Nugent’s art and activism also extended beyond his writing. He was a painter and illustrator whose work explored themes of sensuality, spirituality, and race. He contributed to the movement’s legendary publication Fire!!, an influential but short-lived literary magazine created by Black artists to challenge the social norms and conservative values within both Black and white communities. Though Fire!! only published one issue, it became a defining moment in Black literary and cultural history, emblematic of the Harlem Renaissance’s daring, provocative approach to art and social issues. Later in life, Nugent continued to speak openly about his experiences as a queer man, even as he remained largely unrecognized by mainstream society. He worked as a government employee and remained connected to Harlem’s evolving arts scene.

Black queer history is American history, offering unique perspectives on resilience, artistry, and the fight for equality. To recognize these contributions is to embrace the full spectrum of American heritage and honor the essential roles Black queer individuals have played in the nation’s progress.