With us now in the beginning of Pride Month, new stories and media showcasing LGBTQ Pride in various communities and cultures is everywhere and being celebrated. But with June also being Caribbean American Heritage Month, this month becomes extra special for author and filmmaker Max-Arthur Mantle.

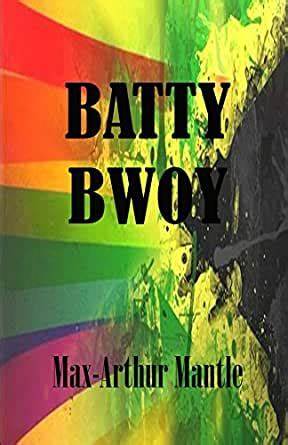

Max-Arthur Mantle is a Jamaican-born author, photographer, and filmmaker whose evocative works explores the rich tapestry of Black and Brown, LGBTQ, and Caribbean narratives. Based in Los Angeles, Mantle’s artistry delves deeply into the intersectional experiences of the Queer Caribbean community, shedding light on stories often overlooked by mainstream media. His 2015 novel “Batty Bwoy” serves as a poignant coming-of-age tale that examines the trials and triumphs of a gay Black Jamaican navigating life in America, highlighting Mantle’s deft storytelling and commitment to authentic representation.

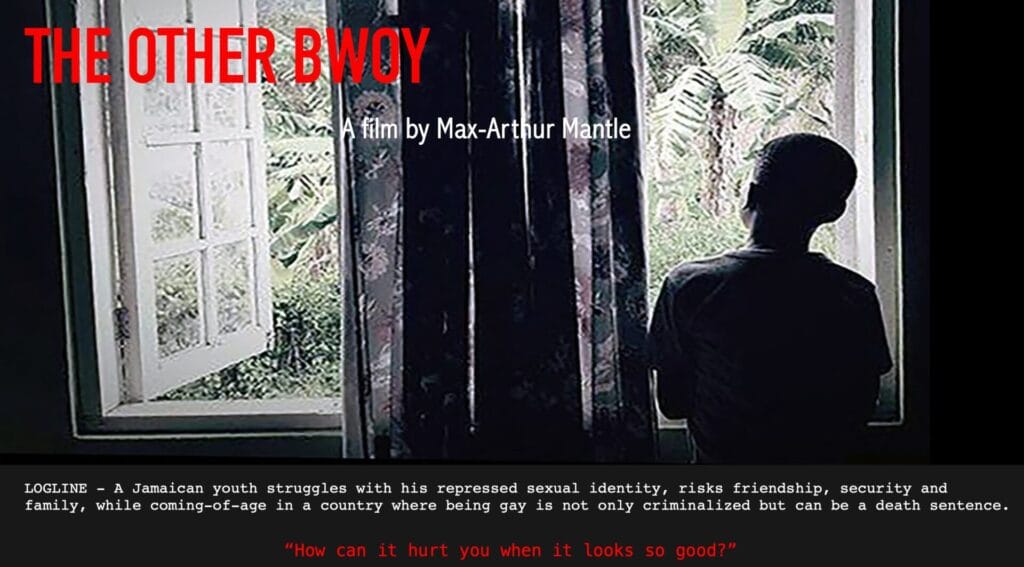

Mantle’s storytelling continues as he is currently developing a feature film titled “The Other Bwoy,” inspired by his novel. This upcoming project aims to delve deeper into themes of homophobia, class, race, and identity, continuing Mantle’s mission to amplify marginalized voices and foster meaningful dialogue through his multifaceted work. Through his compelling narratives and visual storytelling, Max-Arthur Mantle remains a vital and influential voice in contemporary arts and culture.

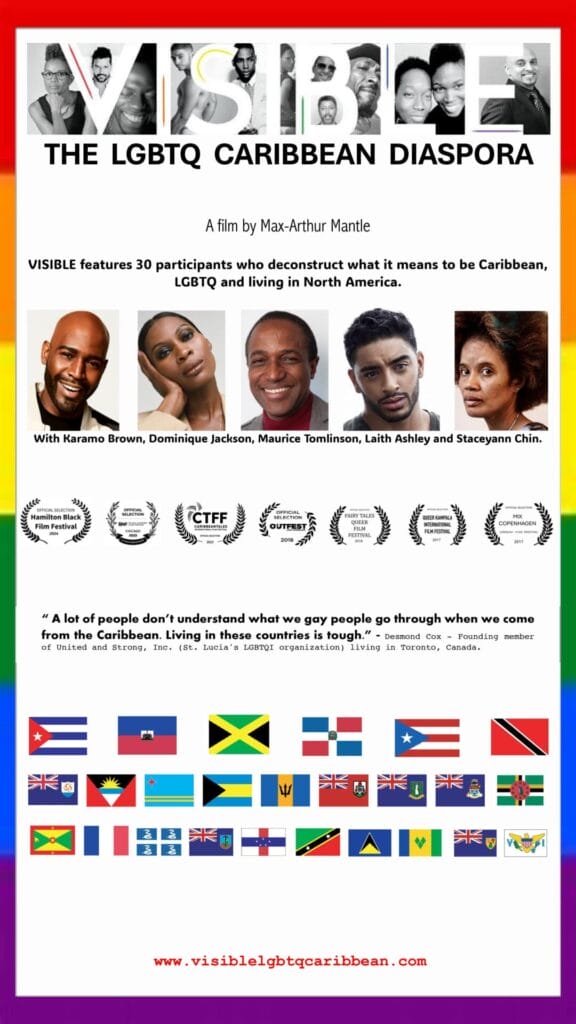

In his latest documentary, “VISIBLE: The LGBTQ Caribbean Diaspora,” Mantle continues to push boundaries and foster understanding through the lens of 30 subjects who intricately deconstruct what it means to be Caribbean, LGBTQ, and living in North America. Featuring notable figures such as Karamo Brown, Staceyann Chin, Maurice Tomlinson, and Dominique Jackson, the 78-minute film has garnered acclaim on the film festival circuit, with screenings at prestigious events like Outfest, MIX Copenhagen, and Queer Kampala International Film Festival. This powerful documentary has also been showcased at Pennsylvania State University, supported by various academic and cultural organizations.

GLAAD had the opportunity to chat with Max-Arthur Mantle to talk further into the process of the film and his advocacy for the LGBTQ Caribbean community.

GLAAD: Can you share any personal experiences or observations that have influenced your work in LGBTQ storytelling?

Mantle: As a writer, I believe we write what we know and have experienced. It can be autobiographical or our truth told with creative license. This has influenced my work, which is centered around highlighting and elevating Black and Brown, LGBTQ, and Caribbean/Jamaican narratives. It was a cathartic experience to write my novel “Batty Bwoy.” A four-year journey for me to return to my Jamaican roots, many of which I had decidedly forgotten and discarded because I was busy trying to be American for what I think that is. And with the book having the title “Batty Bwoy,” which is a hateful slur in Jamaica used to describe gay and effeminate men, I wanted to reappropriate the words to empower my fellow “Battymen” and to boldly setup who I am writing this book for, my community. This was spilled over into my documentary which has been well received. I am energized by things that resonate with me, that are my truth, and has an organic alignment. My storytelling is a narrative that is a minority within a minority. The Black narrative [and] African American narrative, from the lens of being Jamaican/Caribbean and within the LGBTQ community. June is particularly Gay Pride month, but it is also Caribbean American Heritage Month, which celebrates my intersecting identities. And navigating this journey of life, we often, the voiceless and underrepresented, look for spaces where we are seen, which are limited. I want to share these stories from my community, which will resonate universally. What has influenced my work is my way of advocating for those struggling with their queer identities in spaces that are not affirming like Jamaica. My evolution was different, being a “gold-star” gay man, but the typical struggles for many closeted gay men in Jamaica is to disappear in the church, experience the failures of conversion therapy or marry a woman and live a double life. I want my work to serve as a catalyst to changing hearts and minds, not just for the homophobic majority in Jamaica and the Caribbean, but also for my community and to let my 13-year-old self who feared a future of being gay in Jamaica as devastating, to know that it doesn’t have to be that way. He can be Jamaican anywhere else in the world that is going to respect him for who he is and give him the opportunity to thrive.

GLAAD: What made you want to transition from writing to directing your own feature film?

Mantle: I studied journalism and photography at Howard University. I started my career as a fashion photographer in Miami Beach where after 15 years I had achieved my personal goals: magazine editorials, covers, and a photo book. It felt like a natural progression from showing stills to directing moving images.

GLAAD: What was the process like connecting and finding the people you chose to interview for the feature film, VISIBLE?

Mantle: While I was on my book tour for my debut novel “Batty Bwoy” in 2015, it attracted attention from the Black and Brown, LGBTQ+, Caribbean community that resonated with what I was sharing. I returned to Miami Beach and was interviewed by Tim Padgett for the Miami Herald newspaper and WLNR, the local NPR station. He is the writer who wrote the infamous Time magazine article in 2006 labeling Jamaica, “The Most Homophobic Place on Earth.” He used the interview with the premise that Gay Caribbeans like myself could change the hearts and laws of homophobes in the Caribbean. He also wanted an update on the conditions for LGBTQ+ Jamaicans. I had no authority to comment on that because I had migrated legally in 1992 and without any homophobic scare but one incident that was relative to the reality for LGBTQ+ Jamaicans, and I have not returned since. It made me interested in creating a documentary to provide an update. When I approached people in the Caribbean about the project, they were very concerned about being identified publicly as being LGBTQ+ which is still a risk that could compromise their jobs, homes, and safety. So I choose Caribbean people living in the diaspora, particularly North America which is my narrative and they are more open to sharing their stories because they are in liberal spaces where there is no risk to their jobs and living. So I returned to the same places that embraced my novel and found the subjects. I interviewed about 150 subjects and made selections for the final cut based on representation, diversity, and interests. The participants featured also reflect the city they are living in and the cities chosen have the most Caribbean population in North America.

GLAAD: How do you envision your work contributing to the global conversation on LGBTQ rights and representation both as a whole and in the Caribbean community?

Mantle: From my screenings in North American cities, the feedback from the community is positive. Many LGBTQ+ Caribbeans who have left the Caribbean know these narratives because they have lived it, but it is interesting for them to see how homophobia looks in other regions of the Caribbean that are not as popular or featured like Jamaica. The narratives further resonate with LGBTQ+ [individuals] who share the same layers of homophobia from family, school, work, church and society. My work’s contribution to the global conversation on LGBTQ rights is a tool for education and research. I am telling stories that are from my community. The people involved have afforded me trust and access where the narratives are authentic.

GLAAD: How has your work been received by the Caribbean community, both LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ members?

Mantle: Within the LGBTQ Caribbean community, my work has been well received and praised for telling our stories with respect, empathy, compassion, resilience, and authenticity. I have not been in non-LGBTQ Caribbean spaces in decades, but I know what to expect. That is not my space or community. My work is not for them. LGBTQ rights in the Caribbean are moving at a glacial pace compared to what has been achieved in North America, even though we are experiencing rollbacks. Woke society and liberals in the Caribbean think they deserve a merit or an award if they are on the right side of history, because they have been indoctrinated to think that being LGBTQ+ is a sickness and an abomination.

GLAAD: In your opinion, how can the broader film industry better support and represent LGBTQ stories from diverse cultural backgrounds?

Mantle: Our stories from diverse cultural backgrounds are just the tip of the iceberg in garnering quality authentic content. But, the film industry thinks those stories are not marketable or profitable and fears the American audience will not be interested. The Caribbean is one of the most traveled regions in the world. The culture is unique and the tropical islands are breathtaking and affordable. The film industry in the Caribbean, particularly Jamaica, is growing. There is an infrastructure there to make big-budget films that are successful. For example “Bob Marley: One Love” (2024) film that made over $100M at the box office. And LGBTQ stories are comparable because these stories are not rooted in fame, but can crossover to a global audience based on the content. The film industry is oversaturated with remakes, sequels, rom-coms and superhero big-budget films. Many filmmakers are moving towards indie narrative features that tell stories by us for us. More funding opportunities should be available for projects that do not have to be realized by an A-list star. But the business of show business and filmmaking demands that. That’s why when the risk is warranted, LGBTQ stories from diverse cultural backgrounds will find their audience.

GLAAD: Can you share more details about your in-development featured film, “The Other Bwoy,” which is inspired by your novel, “Batty Bwoy”? And how can we keep an eye out for its progress and support?

Mantle: My feature film “The Other Bwoy” is currently in development. It is a coming-of-age story of a closeted Jamaican youth who is struggling with his queer identity. He risks family, friendship and society to explore a life worth living. It looks at homophobia in Jamaica set in the ’90s with intersecting identities around race, class, and nationality. It will make history as the first feature film with LGBTQ themes to be shot in Jamaica. It is aimed to be comparable to “Moonlight” (2016) and “Pariah” (2011). Our cinematographer is Eun Ah Lee, the cinematographer for Patrik-Ian Polk’s films “Blackbird” (2014) and “The Skinny” (2012). We are planning to go into production in November to shoot a proof of concept in NYC, scenes where the protagonist visits America for the first time and is reunited with his mother. We are calling on the support of our wider community and allies to bring it into production. We have created a “Support the Film” page on the website which will serve as the crowdfunding campaign to support the life of the project. There are some unique perks for donors where they will receive pieces of my work in writing (for example, a signed copy of Batty Bwoy), photography (signed copy of my 200-page photo book “The Boys of Summer” featuring over 50 models) and film (set visit, private screening access and business logo in film credits). The principal cast are all identifiable in film/tv/theater with my dream of a special cameo by an internationally known and celebrated Jamaican woman who is a fashion and music icon.

GLAAD: What advice would you give to other queer filmmakers who want to create content about their communities and experiences now?

Mantle: My advice is one that I follow, which is to decide on a project that will become your baby where you can become completely absorb in and committed to having it realized because no one will fight for it like you. When you have that project, surround yourself or seek people who have an alignment. Some people will become interested, but they can only take you to a certain level, maybe preparing you for the next step of the journey. But like the Jamaican saying “one cocoa full basket” which means we should take things one step at a time and eventually we will get where we want to.