This piece contains major spoilers for Life is Strange (2015).

In 2022, Supermassive Games released The Quarry, a game which – like the studio’s previous titles – blends survival horror gameplay with an interactive movie experience. Inspired by 80s horror flicks like Friday the 13th and An American Werewolf in London, it introduces a motley crew of camp counselors and tasks the player with keeping them alive. The Quarry also broke new ground by including Supermassive Games’ first same-gender kiss via a game of truth or dare where Ryan, played by out queer actor Justice Smith, has the opportunity to kiss fellow camp counselor Dylan. Regardless of whether the player initiates the kiss, Dylan speaks candidly about his interest in Ryan, and the two are given opportunities to flirt and, more importantly, confide in one another between moments of peril. And yet, despite both Ryan and Dylan being able to die in various barbaric ways if players make a wrong choice or fail to react quickly enough in dangerous situations, The Quarry never feels hostile to its queer characters.

Who’s team Dylan x Ryan? 💘 #TheQuarry https://t.co/C9NGs9Xapr

— Supermassive Games (@SuperMGames) June 16, 2022

Games that center branching narratives often use the possibility of character death to raise the stakes for decisions that players will make. The Quarry, a cinematic horror, Life is Strange, an episodic adventure, and Baldur’s Gate 3, a party-based roleplaying game, cover a range of genres where the player’s choices can potentially result in the death of an LGBTQ character. And yet, of those three games, only one falls into the dreaded bury your gays trope, a long-standing phenomenon in media where LGBTQ characters die at a disproportionate rate or are denied happy endings via an untimely death. However, when the power of choice lies in the hands of its players, this trope can be more difficult to identify. After all, the death of an LGBTQ character can be blamed on a gameplay mistake or a consequence of a narrative decision. But not all choices in games are created equal.

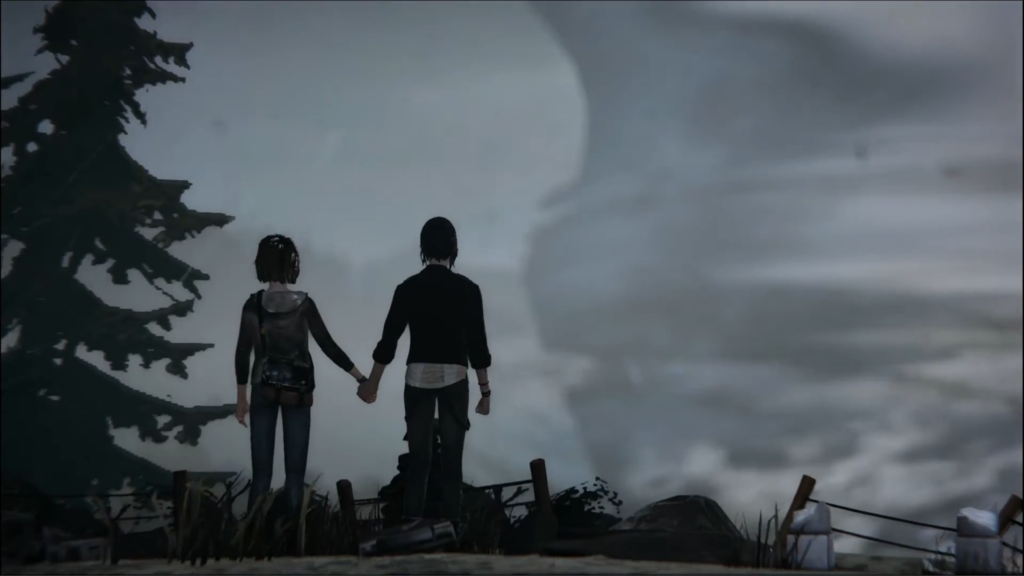

With the return of Max Caulfield in Life is Strange: Double Exposure, fans of the series have questioned how the new release will deal with the fact that the original Life is Strange (2015) has two vastly different endings depending on the player’s choice. The final decision in Life is Strange mandates a sacrifice: allow Max Caulfield’s hometown to be destroyed by a storm along with everything and everyone in it or allow Chloe, Max’s romantic interest, to die in order to save the town. If players internalize the oft quoted Star Trek II: Wrath of Khan saying, “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few…or the one,” then the choice is simple: Chloe must die. Regardless, there is no truly happy ending for Max Caulfield and Chloe Price, and the players are made complicit in either the death of a major queer character or the destruction of a town of innocent people.

The problem with the moral quandary posed in Life is Strange has little to do with needing to weigh the death of one versus the death of many. Instead, the problem is that if Max chooses to save Chloe Price, it parallels the common anti-LGBTQ narrative that queer relationships are a danger to society. Though the game is never explicit about what causes the storm that threatens the lives of Arcadia Bay, the characters theorize it was a result of Max’s time travel abilities, which she first used to save Chloe from death. It uncomfortably evokes the ways in which LGBTQ people have even been historically blamed by extremists for disasters, including Hurricane Sandy, 9/11, global warming, and other tragic events. Some religious leaders even go as far as to proclaim that embracing the LGBTQ community will cause the destruction of the world itself.

Whether or not using her powers to save Chloe actually caused the storm, Max blames herself for its creation. Considering Life is Strange was developed during the height of this LGBTQ doomsday rhetoric, the ending choices could be interpreted as an unfortunate coincidence or perhaps a result of unconscious bias. But most of all, it is a reminder that even games with good intentions can still fall prey to harmful tropes.

By all accounts, the release of Life is Strange in 2015 changed the narrative adventure genre. It was a revolutionary exploration of teen life and queer romance with a teenage girl in a lead role, a decision that developers revealed was considered unprofitable by publishers. Having a queer woman as the sole protagonist of a major release was groundbreaking territory, predated only by Ellie from The Last of Us: Left Behind. To this day, Life is Strange is still regarded as one of the flagship titles in queer video game history and is often cited as a game that contributed to players queer awakenings. Max Caulfield is an unlikely hero that, with the player’s guidance, slowly grows into her self-worth and confidence; she’s an aspirational story for many LGBTQ youth struggling to do the same. If any game needed to get its queer romance correct, Life is Strange was the one, so it is unfortunate that despite its inclusion of relatable characters and stories that many LGBTQ gamers resonated with, the story stumbles at its most pivotal moment.

thank u max & chloe for my 2015 gay awakening pic.twitter.com/EtnUB80c5e

— azra 🇵🇸 (@papirfecni) June 17, 2021

Life is Strange is no secret trojan horse of anti-LGBTQ rhetoric that wants to warn its players about the dangers of queer relationships, but it does find itself unwittingly replicating that narrative. LGBTQ stories are overwhelmingly fraught with untimely deaths and brutal sacrifices, and Max and Chloe are another victim of a withheld happy ending for LGBTQ couples. Prioritizing their relationship over the lives of others invokes both shame and guilt, feelings that are all too familiar for players that have yet to accept their own sexuality. Instead, they are dissuaded from living their truth in the face of a “greater good.”

So how can player-driven games ensure they do not unintentionally force players to “bury your gays” and also limit the potential for players to target LGBTQ characters without resorting to giving them plot armor? After all, while Life is Strange forces players to choose between two uncomfortable, even horrifying, endings, risk and sacrifice are important in raising the stakes of decisions that the player must make.

Players on their first playthrough of The Quarry may overthink early-game decisions in fear of losing one of the nine camp counselors. However, it turns out that it is actually far more difficult to kill off the protagonists than some might think. In Dylan and Ryan’s case, they cannot be killed until late in the game, meaning players cannot prematurely – or intentionally – end either of their storylines before they can bond and open up to each other.

And despite the brutality of each possible death in the game, The Quarry does not require any of the counselors to sacrifice themselves for the survival of the group. Choosing dialogue options that deepen the relationship between Dylan and Ryan is never punished by the game, and the player’s possible attachment to their dynamic is never exploited to manufacture a difficult or tragic decision. Instead, their queerness exists independently from the unfortunate horror genre they find themselves in. Their queeness is a part of their character arcs, not a factor that determines or even influences whether or not they live or die.

Much of what makes the “bury your gays” trope so pernicious is that LGBTQ characters in media are historically very rare, so their deaths often entail the loss of all LGBTQ representation within their game. Baldur’s Gate 3 addresses this problem through its approach to balancing player choice and character death. Though the vast majority of characters in the game can be permanently killed, it is the sheer number of LGBTQ characters that ensures the game never feels as if it is reinforcing harmful tropes. Inclusive world-building is foundational to Baldur’s Gate 3, and many of its characters, major and minor, are canonically LGBTQ. In fact, two of the game’s most prominent and powerful characters, Isobel and Dame Aylin, are explicitly depicted in a romantic relationship. Both characters are essential to the story and will be encountered by every player who follows the main quest – not siloed to an optional side plot, as is so often the case.

Baldur’s Gate 3 does more than just populate its world with a plethora of queer NPCs. All companions are romanceable by player characters of any gender and a select few, namely the druid Halsin, are openly polyamorous. The character creator also allows players to select between she/her, he/him, and they/them pronouns and will be addressed accordingly, even resulting in gender-specific interactions that allow for unique conversational opportunities. Perhaps the most important choice that Baldur’s Gate 3 makes, however, is that despite providing a near sandbox-style world where players can save villages, wreak havoc, or even conquer the world, killing off the game’s characters or intentionally avoiding them restricts players from accessing substantial portions of the game’s content. Many have both narrative and gameplay significance that benefit the player if helped or kept alive, especially when it comes to the endgame where players can rely on the allies they’ve made to assist them. It is a clever choice to offer gameplay flexibility while also subtly dissuading players from certain antagonistic actions.

Player choice is the foundation that Baldur’s Gate 3 was built on. After all, it seeks to capture the magic and flexibility of a Dungeons & Dragons campaign. However, the game is at its best when players choose to pursue character-driven quests and engage with everything the world has to offer, and this is exactly what makes its LGBTQ representation so impactful. Ignoring its queer characters makes for a shallower story; it is a testament to how a diversity of people and experiences enrich video game worlds in ways that demand exploration. Admittedly, it is no easy feat to keep everyone alive in Baldur’s Gate 3 without lucky dice rolls or reloading saves, but the viral popularity that the game enjoyed in 2023, especially within the LGBTQ gaming community, is an impressive feat for a game that no two people are likely to experience in the same way.

Thankfully, the Life is Strange series has shown improvement in regards to its LGBTQ representation, with Life is Strange: True Colors winning the 33rd GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Video Game. The romance plotlines for Alex Chen, the protagonist in True Colors, exist parallel to the main plot of the game, allowing players to choose who Alex ends up with if she builds a relationship with either of the love interests. Hopes are high that Life is Strange: Double Exposure will not repeat the mistakes of its predecessor – inadvertently associating queer romance with disaster or repeating the same “bury your gays” dilemma that was presented in the original – while still offering players the chance to guide the story in drastically different directions. It is worth noting that the developer of the original Life is Strange, DONTNOD, is not returning to develop the sequel. Instead, Deck Nine Games, developer of True Colors, is the studio continuing Max Caulfield’s story.

Although The Quarry never fully provides closure to the relationship between Ryan and Dylan, the game does not close the door on a future for them either. Importantly, both characters remain alive in all the “good endings” – never cornered into any self-sacrificial moment or treated as dispensable characters. Developers are ultimately responsible for the narrative choices available to players in the game. With the creativity in video game storytelling, there are more interesting risks to take that do not include burying your gays, and it is past time to retire the harmful and overused tropes that treat LGBTQ characters as collateral.