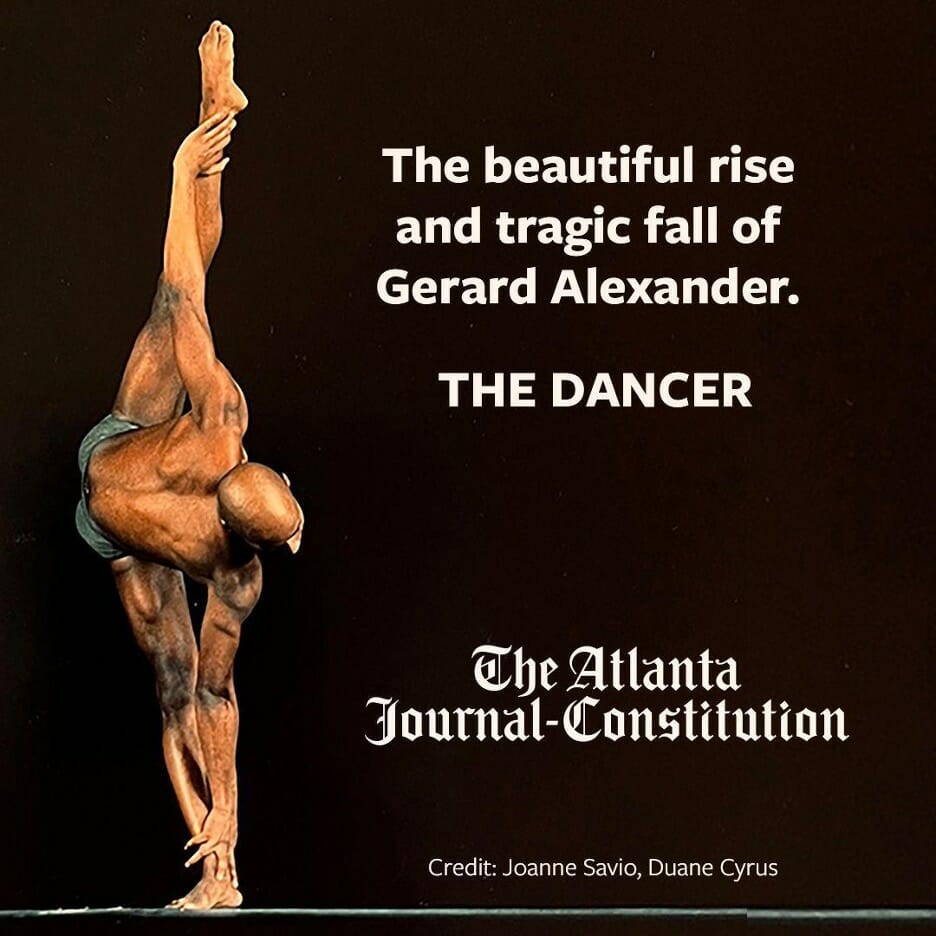

How does an incredibly gifted dancer, often referred to by many as the “Black Baryshnikov,” spend the last years of his life homeless, addicted to drugs, and disconnected from friends and family, only to be found dead from multiple gunshot wounds underneath an overpass bridge in Atlanta? It’s one of many sobering questions explored in the new documentary “The Dancer” produced by The Atlanta Journal Constitution’s award-winning visual journalists Ryon Horne, Tyson Horne and award-winning senior reporter Matt Kempner.

“The Dancer” made its Atlanta debut on July 12 at RoleCall Theater at Ponce City Market. An intimate invite-only audience, including AJC subscribers, was the first to screen the tragic rise and fall of Gerard Alexander’s life and career. The screening follows the AJC’s June release of Kempner’s two–part story on Alexander—” The Dancer: The Beautiful and Tragic Life of Gerard Alexander,” which details his humble beginnings in Paterson, New Jersey, to his early dance training in Newark with mentor Alfred Gallman, to the launch of his professional career and the embracing of his unapologetic queerness.

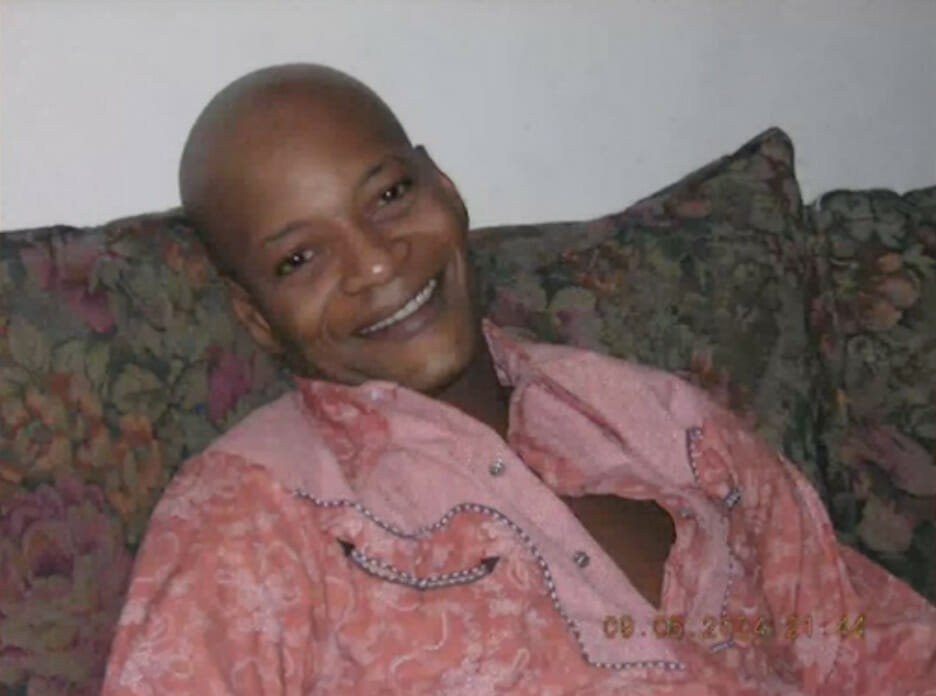

“He embraced a reputation in some dance circles as a party guy, a stylish vogue dancer and a sometimes drag queen,” writes Kempner in “The Dancer.” He could cause a stir when he showed up at auditions in New York. And he didn’t shy away from being out as a gay man.”

At the age of 19, Alexander won a coveted spot in Micahel Jackson’s “Bad” video out of hundreds of dancers.

“If God created somebody who had everything to be a dancer, that’s what he got,” Gallman says in a quote from AJC’s “The Dancer.”

“Supple back. Flexible body – rare in a male dancer, especially at the time. Powerful legs. And the feet. Stunning feet. Perfect feet. Big feet that could curve, along with his toes, into a seamless C shape. You can’t have bad feet and be a successful dancer,” Gallman said. “He had feet that would rival any ballerina.”

Admittedly haunted by his story, Kempner interviewed 40 people more than once over five-months to provide a detailed and accurate depiction of Alexander’s life. For as much as he was a consummate professional, Alexander had secrets. And ever so often, his drug addiction consumed him, causing him to act erratically, missing rehearsals and performances.

From The Dancer Part 2: An Unexpected Finale:

One of his regular gigs was with Wylliams/Henry in Kansas City, where he would stay for weeks at a time, rehearsing for upcoming shows.

It was during one of those stints that he went AWOL.

Days before a big performance, he went out to dinner with other dancers, then made some stops at local clubs. At some point, he separated from his friends.

That night, Gerard didn’t make it back to the home where he was living while working in Kansas City. He didn’t return the next night either.

And when it was time for rehearsal, he didn’t show up or answer his phone.

The people at Wylliams/Henry grew frantic. They called the highway patrol, then hospitals in Kansas City and St. Louis, where they thought he might have gone.

Was he safe? Was he alive?

Two of the dancers used to privately refer to him as “Bambi,” because they thought his openness and gentleness made him vulnerable in a harsh world.

The decision was made to call Gerard’s partner, James Rosheger. Come to Kansas City, he was told. Gerard has disappeared.

Meanwhile, the company’s director had the upcoming show to think about. Gerard was, as always, one of the lead dancers and was scheduled to appear in numerous pieces.

“I thought, ‘What are we going to do?'” Henry recalled.

She had to figure out how to rework the show without him.

Then two dancers driving down a main strip in Kansas City saw a disheveled man walking along the sidewalk.

Wait. Was that Gerard?

They pulled over and ran to him. He was shirtless, in flip-flops, and appeared to be wearing the same brown pants he’d last been seen in about a week earlier. He didn’t look right. He was clearly unbathed and sweating profusely. Anyone who didn’t know him might have thought he was homeless.

The women urged him to get in the car with them. He refused.

I’m OK. I’m OK, he said, crying.

One of the dancers gave him her cell phone to keep, pleading with him to call his boyfriend. He didn’t.

Alexander’s story is not singular

As he often did, Alexander bounced back and continued to thrive professionally for a while with a teaching job at The Atlanta Ballet and the purchase of a Buckhead condo, all of which he lost due to drug use, prompting the beginning of a decades-long journey of being unhoused at tent sites near the intersection of Atlanta’s Buford Highway and Lenox and Cheshire Bridge roads.

“Like Gerard’s dance colleagues in Kansas City, caseworkers worried about his vulnerability on the streets,” writes Kempner in “The Dancer.” “Some people who are homeless try to present a tough exterior. Gerard didn’t. He also faced health issues. He had hepatitis. He had been [living with HIV] for years and had to stick to a strict drug regimen to keep the virus tamped down. A social worker also concluded he had symptoms consistent with bipolar disorder and PTSD.”

“This is an every man’s story that needs to be told for so many Black men that danced,” said Atlanta choreographer Daryl Foster (who shared a similar career trajectory as Alexander at Dayton Contemporary Dance Company in Ohio) to Kempner during a talk-back moderated by the AJC newsletter editor Najja Parker following the screening.

“If I were born five to seven years earlier, I would be dead right now,” Foster said. “80% of all of the Black men that were born five to seven years before me are all dead. I don’t have mentors. I don’t have a lot of people that I can call up. All the ones that are still alive are in my phone right now. I know them all because it’s that few of them,” he said over the silent room. “And I think the real story here is that what happened to Gerard has happened to hundreds of Black men who danced.”

In the winter of 2021, an Intown Cares team leader, Tracy Woodward, secured an apartment for Alexander. He returned to the homeless encampment again to escape loneliness and be amongst friends.

“While out at the muddy encampments, Gerard’s extremities got cold and wet, Woodward said. “That led to frostbite. They had to cut off all his toes.”

Last year, on April 25, Alexander’s 55th birthday, Atlanta emergency dispatchers received a 911 call. Alexander was dead. Shot seven times, including once through the heart, according to an autopsy report.

“We see this roller coaster, but he was the same guy,” said Kempner during the talk-back. “This gentle soul. This kind, kind man, this giving person. Throughout his life, it seems that whether he was in a tent, in a filthy area, or whether he was in his own home, he was trying to make the world around him beautiful. So, to me, this wasn’t only a tragedy. There really was remarkable beauty in his life.”

Watch the 30-minute “The Dancer” documentary in full here.