Newark, New Jersey LGBTQ activists are organizing to heal their city from redlining – the systematic denial of services, like mortgages, insurance, and other financial services, often based on race or ethnicity – and environmental discrimination to build a healthy, clean, and affordable place where bodily autonomy is never in question.

These local leaders understand the convergence between environmental justice and queer liberation and seek to educate others on how queer-centered action unlocks freedoms and possibilities for all.

The City of Newark, home to state schools Rutgers University and a State University of New Jersey campus, has a majority Black, Brown, immigrant, LGBTQ and low-income population.

This population has experienced escalation in raids (some deemed illegal by residents and the city’s mayor) by U.S. Immigration and Enforcement (ICE), but also bears the ongoing burden of neighboring toxic waste facilities including three power plants, with a fourth power plant looming over residents of the 26 sq mi city.

Local activists are scheduled to host a protest against the backup power plant March 13 at the Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission at 10:30 a.m.

From a national perspective, The Trump Administration has slashed well-established environmental justice policies. The Administration also instructed agencies to eliminate environmental justice-related roles in tandem with the reversal of diversity, equity and inclusion policy, AP News reported.

The GLAAD Media Institute – GLAAD’s training, research, and consulting division of the organization – traveled to Newark to discuss with local leaders their top community priorities for year.

Right now, the environment and its impact on quality of life is their main concern.

“Fighting for LGBTQ rights in Newark in terms of environmental justice, in terms of housing justice, it makes a lot of sense to me because we are the communities that have been segregated to one of the last affordable places to live in the country.” JV Valladolid, environmental justice organizer for Ironbound Community Corporation said.

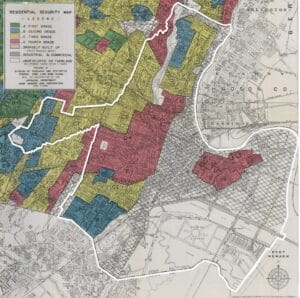

“Unfortunately we are also communities that are living in the historical lines of redlining, which means a lot of toxic sites have been placed right in our neighborhoods,” Valladolid continued.

Historically, redlining has resulted the divesting of neighborhoods often populated by low-income communities by coloring out “dangerous-to-invest-in” areas in red. While the practice is outlawed today, redlining’s effects linger in major cities throughout the country. Newark is one of those cities, and holds the great burden of holding the entire state on its shoulders.

Valladolid aims to relieve that tension with a variety of coalition partners.

View this post on Instagram

Next to Valladolid stood Ironbound Community Corporation’s Environmental Policy Analyst Chloe Desir who says she fights for LGBTQ people because she and Valladolid are LGBTQ people, but also because LGBTQ people among Brown, Black, disabled, and low income communities “are the same people that have been fighting [these] same fights for decades.”

Desir calls Newark a melting pot where people from all over the world come together to find ways to support themselves, their at-large community, and families.

“Newark is definitely a microcosm of this country,” Desir said as a result. “Newark and especially in the Ironbound, we are predominantly a foreign born city and community, so that means we have so many different people coming in from different walks of life and different identities that contribute to the community.”

View this post on Instagram

The governor’s seat is up for election in the Garden State in a highly contested election that will mark the future policy of Newark and the state as a whole. In fact, Newark’s Mayor Ras Baraka will be running up against Trumpist Jack Ciattarelli, among other candidates.

Desir said these contributions to Newark, and the Ironbound, look like building art scenes, culture, and coalition. For example, Newark LGBTQ Film Festival spoke to GLAAD about their work in the community. Going to public school GSA’s (Gender and Sexuality Alliance) to talk to youth about screenings, and opportunities to work in expanding Black, Brown, and LGBTQ representation in film.

Director of the Newark LGBTQ Film Festival Denise Hinds says joy is imperative to the justice she and people like Valladolid and Desir are fighting for. She says that is why representation in the media is also important. The film festival materialized during the COVID-19 pandemic, and has flourished ever since.

“LGBTQ folks in Newark really needed something that spoke to them about who they were, and what they were about,” Hinds said. “We don’t see a lot of representation in films on a regular basis, especially films that focus on queer BIPOC folks. That was our dream, to be able to bring these films to Newark, and really throughout New Jersey, but really focusing on the folks in Newark and really focusing on something they can see themselves in.”

Hinds says it means so much to bring joy to LGBTQ youth in Newark. Additionally, the director is excited to continue building community among Newark’s LGBTQ youth with their annual film festival starting in the first week of May.

View this post on Instagram

Like Valladolid, and many of the youth Hinds works with, disability and human rights activist and history-making journalist Steven McCoy was born and raised in Newark, and like the Newark LGBTQ Film Festival, he works as a change agent through his nonprofit Spoken Heroes. His organization has a mission to “empower and support disabled grade school and college students by providing them with essential resources” throughout Newark and the country.

McCoy, presumably the world’s first deaf and blind Black journalist, founded Spoken Heroes after years of discrimination and ableism as a result of Usher Syndrome, a retinal eye disease which led McCoy to experience blindness and hearing loss, McCoy told GLAAD.

He still lives in Newark, and loves his hometown, even when he felt Newark didn’t support him.

“I love where Newark is headed because there’s so much growth than where it was before. I used to feel that Newark did not support me,” McCoy said. But once he left and returned, he found it his mission to stay and keep investing in the city that raised him.

“But what pushed me to now, at this point, to get involved more when it comes to the LGBT community, it’s because now I have students who are queer or trans,” McCoy continued. “It’s my responsibility to make sure that I’m educating myself and that I’m able to communicate with them efficiently, and make them feel absolutely included.”