A follow-up to his Independent Spirit Award-winning pandemic pic 7 Days, filmmaker Roshan Sethi premiered his third feature, A Nice Indian Boy at SXSW this year. A Nice Indian Boy introduces us to an modest, yet charming doctor named Naveen Gavaskar (Karan Soni). Naveen is openly gay, but true to first-generation-children-of-immigrants form, his parents Megha & Archit (Zarna Garg and Harish Patel) are still trying to get used to it. They are a mix of accepting and resistant while trying to police his sister’s Arundhathi (Sunita Mani) marriage — which is crumbling.

Things start to change when Naveen meets the equally charming Jay (Jonathan Groff). The two hit it off and before we know it, it becomes a Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? situation. The twist? This white boy was adopted by Indian parents, who have since died.

Based on the play of the same name by Madhuri Shekar and adapted for screen by Eric Randall and also starring Peter S. Kim and Sas Goldberg, Sethi points out that the original concept of Shekar’s play was born out of the pressure she was facing to not marry a white guy. From there, the gay narrative was folded in as a way of testing the hypothesis of what is more shattering for a family: the fact that their daughter is getting divorced or that their gay son found a white partner. “She tied all those things together in an interesting and original way,” Sethi told GLAAD in a recent interview.

“The play is much more contained as you might expect,” Sethi continued. “It was adapted by a screenwriter Eric Randall, who is gay but not Indian… and written by someone who was straight but not Indian. In the end, their influences came together to produce the movie.”

When Sethi and Soni, who are a couple in real life, joined the project, they added their personal experiences but Sethi said it was Randall and Shekar’s work that helped expand the universe.

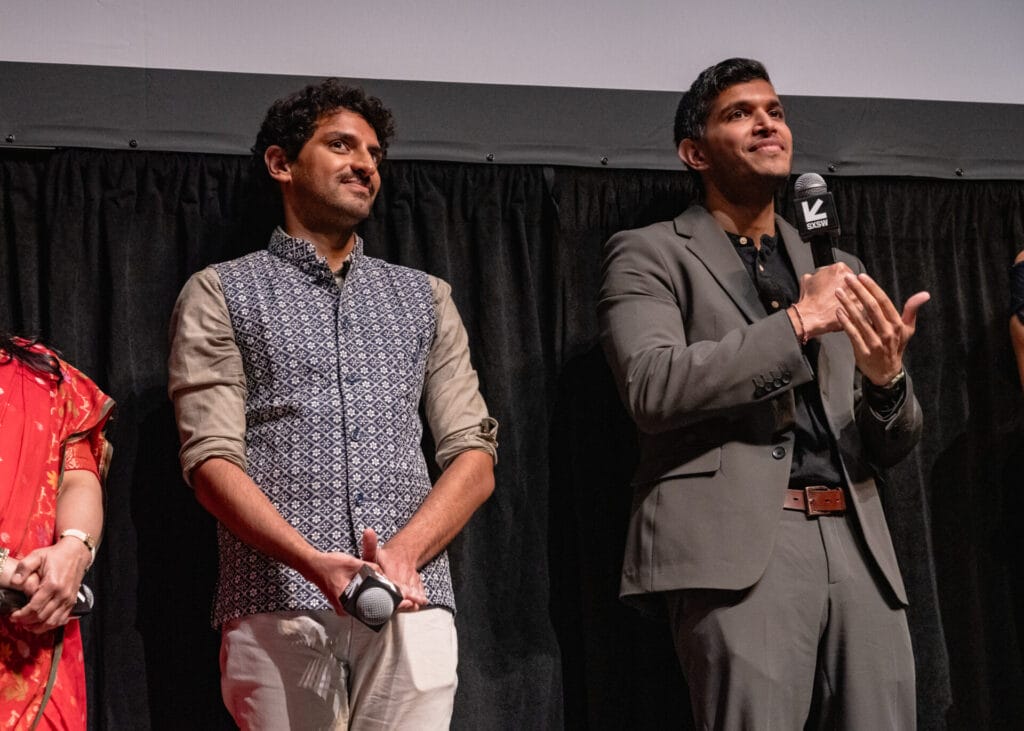

GLAAD had the opportunity to speak to Sethi and Soni at SXSW before the premiere of A Nice Indian Boy. Read the full interview below.

A Nice Indian Boy is a thoughtful intersection of being queer and South Asian, something we don’t often see on screen in American cinema. How did you navigate creating a universal story from a narrative that is so specific when it comes to representation?

ROSHAN SETHI: I think in general, the whole concept of representation is one I struggle with because I have been in this industry since 2015 when it was about as racist as it could have been, it was probably even worse before then – but when I arrived in 2015, it was bad. And there was very little diversity on screen. Initially, I felt so excited about the idea and the concept of representation, which has always had this double side, which is the burden. Because there’s so little of it, it must represent it accurately. Now I’m in a place where I think if you don’t think about the representation part of it, then you don’t feel so burdened by the need to accurately represent and carry the weight of that. Where I do think the industry has come to regard these movies as existing for the sake of politeness; to reflect the niche experience of life and they’re not meant to have any intrinsic artistic value. They’re there to showcase minorities and demonstrate their politeness towards the cause. Those movies are actually doing, I think, a disservice. Ultimately, what they’re creating in the minds of buyers, executives, and gatekeepers – who are still mostly white – is this expectation that art exists to diversify and represent as if it’s being shown on a platter and not have a concept or a premise. A movie that I would say is an example is Bros, where the premise is that they’re gay. It doesn’t have a premise beyond that. It’s a showcase. The movie is historic because it was the first large studio gay rom-com.

Karan, you have been in many films including indies like 7 Days as well as huge blockbuster franchises like Deadpool. Do you navigate one space differently than the other when it comes to representation?

KARAN SONI: I don’t ever think [lack of representation] is my responsibility to solve (laughs)

SETHI: He was playing terrorists – I mean, he was auditioning with an AK-47!

SONI: I always feel like the people that are narrow-minded in what they make and all the time, whether it’s a studio or independent film, I’m always like, it’s their loss. They aren’t tapping into my full potential. I will follow good work. I feel like any time you’re trying to engineer too much of this movie to “say this”, it’s often not entertaining. It feels like homework. That’s how I feel as a viewer – especially during award season. I feel this pressure sometimes to have to like something because it’s engineered that way; versus something like American Fiction this year. I just had a blast and it had so much to say. I would have watched that movie outside of Oscar season. I’m always like, is this [movie] entertaining? Exciting? Also, when reading something, I imagine the trailer. Does it excite me? It’s a double bonus the story naturally has something to say – but also you can just watch it as a movie. Get Out is also a good example. It’s truly one of the most entertaining movies, but if you dig one or two levels deeper, there’s so much. [A Nice Indian Boy] is naturally like this. The characters are not just there to represent. They’re fully formed characters – including the parents. The movie is just a gift. It was something that just came to me and I was like, “Yes, I will be a part of that.”

Jonathan Groff’s character Jay being an adoptee of Indian parents was very interesting and it adds the conversation of cultural appropriation into the mix. How did that translate from the play to the screen?

SETHI: [The play] pushes that concept way further in every way in a way you can’t do on screen. We live in a more politically conscious era and I think that changes the conversation around appropriation. What I felt when I read [the script] was that it was very crazy and very messy. I kind of liked how it challenges this whole thing that we’re constantly talking about which is his culture and what it even is. As much as I identify as Indian and talk constantly about being Indian, I know so little about India and am frequently saying things that are proven to be completely false about that country. [Karan] was born and raised in India. I was born and raised in Canada and have a dim, distant notion of what India is. So it’s weird that even in our own personal experience, I do sometimes feel like I am masquerading as Indian. I can imagine meeting someone like [Jay] who would know more, but it exposes something interesting in the storytelling. I think the movie would be worse without it actually, as provocative as it is.

SONI: It’s not as simple as he’s just white. If he didn’t know about the culture, would the parents have the same problem? So it challenges the central conflict in a very interesting way where you say, “Okay, now let’s have a conversation. What’s making you uncomfortable about all of this?” It was a very interesting part for Jonathan because the family unit is such a big part of the movie, and then he’s kind of disrupting it. That person disrupting should be messy and interesting.

SETHI: The neater version of this movie would be an Indian guy brings a guy home to his family, and they freak out because they didn’t know he was gay – and it would also be the most boring in a weird way because Madhuri and Eric have each complexified it in crazy ways by introducing the sister subplot, which is very crucial element to it but then also the fact that he is white – but Indian, but not Indian – that the whole thing makes it resist the cliches and the stereotypes of the genre.

SONI: What is interesting about my character who’s struggling with accepting himself and finding someone who accepts a version of his culture so strongly – we don’t see the way he grew up. Clearly, being brown in America has had some impact on him, and I think draws him closer to that character for a reason, and then the fact that they have an Indian wedding celebration at the end, they can both appreciate what that is more.

There are many heartfelt scenes in the movie, especially between Naveen and his dad. Without giving anything away, Karan shares a fantastic moment with the wonderful Hamish Patel. I was pleasantly surprised to see an equally special moment between Jay and Naveen’s dad.

A lot of Asian culture is so family-oriented and a lot of Americans are jealous of that. They’re always like, “I wish I saw my family more”. It’s interesting that Jonathan plays an orphan and that he feels most at home here. Then my character wants acceptance from his own family and it takes him meeting this guy to get it.

How do you think A Nice Indian Boy challenges greater conversations of representation when it comes to Asian American visibility?

SETHI: I’ve now been fortunate to make three movies with Indian leads, which is an increasingly hard thing to do. What is revolutionary about [A Nice Indian Boy] is that they are Indian, but the premise of the movie isn’t, “What if these Indians talk to each other?” They just happen to be Indian and in a way you could substitute them for another ethnicity or culture and have an experience that means just as much. As South Asians, I don’t know the spectrum of roles that are typically offered but in general, actors like Sunita don’t get to play a messy sister or a gay lead of a love story like [Karan]. I see what [Karan] is auditioning for because I’m reading those sides with him. This kind of material is not exactly flooding in. It’s really rare to have good writing. When I was watching the Oscars, so much of what brings people to that stage, especially for acting, is good writing and good people. With [Da’Vine Joy Randolph], we’re never going to realize the full extent of her talent unless we write for her. You can imagine someone of her considerable talent disappearing into the big flood of this industry and never being recognized in the way she was recognized [at the Oscars] – the same is obviously true for Lily Gladstone who has been around for a long time and been unrecognized for most of her career.

In addition to A Nice Indian Boy, the two of you have worked together on 7 Days. What has it been like working as a real-life couple?

SETHI: It’s very peaceful and not like, what you might think it would be like. It is a very loving thing, to just be able to see your partner’s talent – it’s not something everyone gets to experience To get to see him act is a special thing, because it’s a whole other side of him that I might not otherwise have known. So I really enjoy it. I do not enjoy doing the auditions and reading the sides. (laughs)

SONI: 7 Days was a very stressful experience because it was shot in eight days in a heatwave in Palm Springs in September of 2020 – super COVID, scary stuff. We had never worked with each other before and we learned a rhythm there of how to communicate because it’s not the same as just taking your relationship and then putting it in a work situation, because there’s a hierarchy dynamic. He’s a director and I’m an actor. There are different jobs and roles you have to play and change. I think we learned a lot of that in the first movie. This one just just felt like joy, because we’ve figured out communication well.

At the end of 7 Days, we had this appreciation of what the other person can bring. I feel so comfortable acting when he’s there because I feel like the performance is way better because he knows me so well and he knows what I can do. I just know he will be very honest… and the other thing I appreciate about him as a director is that he’s very fast. It’s just a very great environment to work in.

When the person who is in charge knows you so well and wants you to succeed, it’s so pure. On top of that, the subject matter of this movie – we could never work on something more personal. We will make other things but how lucky to be able to make this ultimately joyful, positive movie, and put so much into? It’s so rare, it doesn’t happen. I think we were both very conscious and aware of that. It was a seamless, happy experience.